Duncanson M, Roy M, van Asten H, Oben G, Wicken A, Tustin K, McAnally H and Adams J. (2022)

Child Poverty Monitor 2022 Technical Report. Dunedin. NZ Child and Youth Epidemiology Service, University of Otago

Introduction

The Child Poverty Monitor is a partnership between the J R McKenzie Trust, the Office of the Children’s Commissioner, and the New Zealand Child and Youth Epidemiology Service (NZCYES) at the University of Otago.

This tenth annual Child Poverty Monitor technical report begins with stories from communities in Aotearoa where mokopuna are supported to thrive. These stories point to the world we are committed to, a society where every child is valued, and enjoys their rights to thrive and to achieve their potential.1, 2 Mokopuna know only too well the barriers that stop them from enjoying their right to a good life. Because of poverty, racism and discrimination, whānau and children struggle to meet everyday needs and miss out on opportunities that are taken for granted by most in Aotearoa.3 In reflecting on what makes a good life, children and young people talk about the importance of strong family relationships, with supported parents, in a community that loves and accepts them.4

The technical report presents the most recent child poverty statistics with commentary on how well Government targets are being met for different groups of children. Conditions in which children and whānau live their lives day-by-day are reflected in statistics regarding financial assistance, good work, suitable housing and food security. Child poverty related indicators in health include access to primary care, as well as deaths and hospitalisations of children, and immunisation coverage. Data on aspects of child safety underscore the importance of children being loved and nurtured in safe environments. Education indicators provide an indication of the opportunities for learning available to mokopuna.

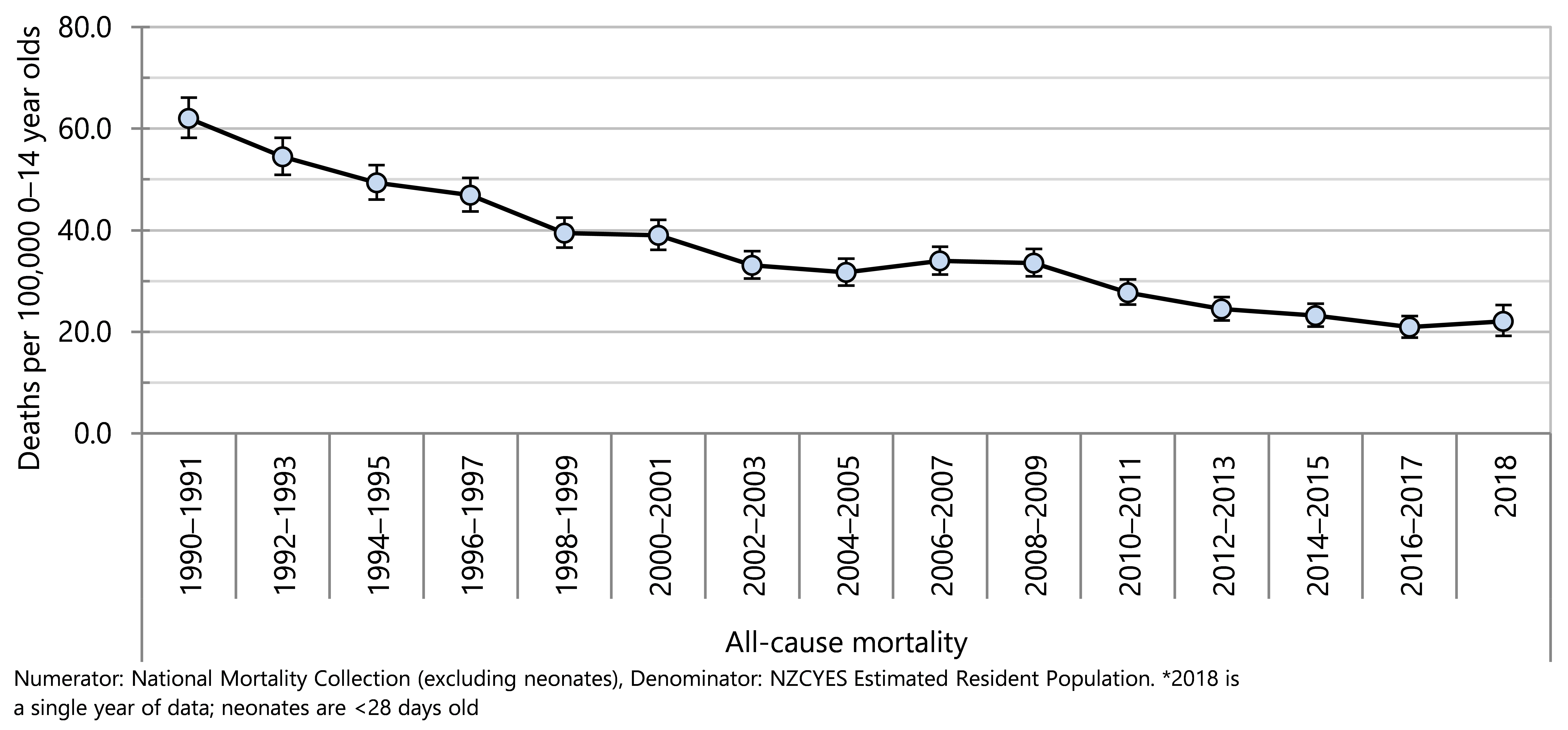

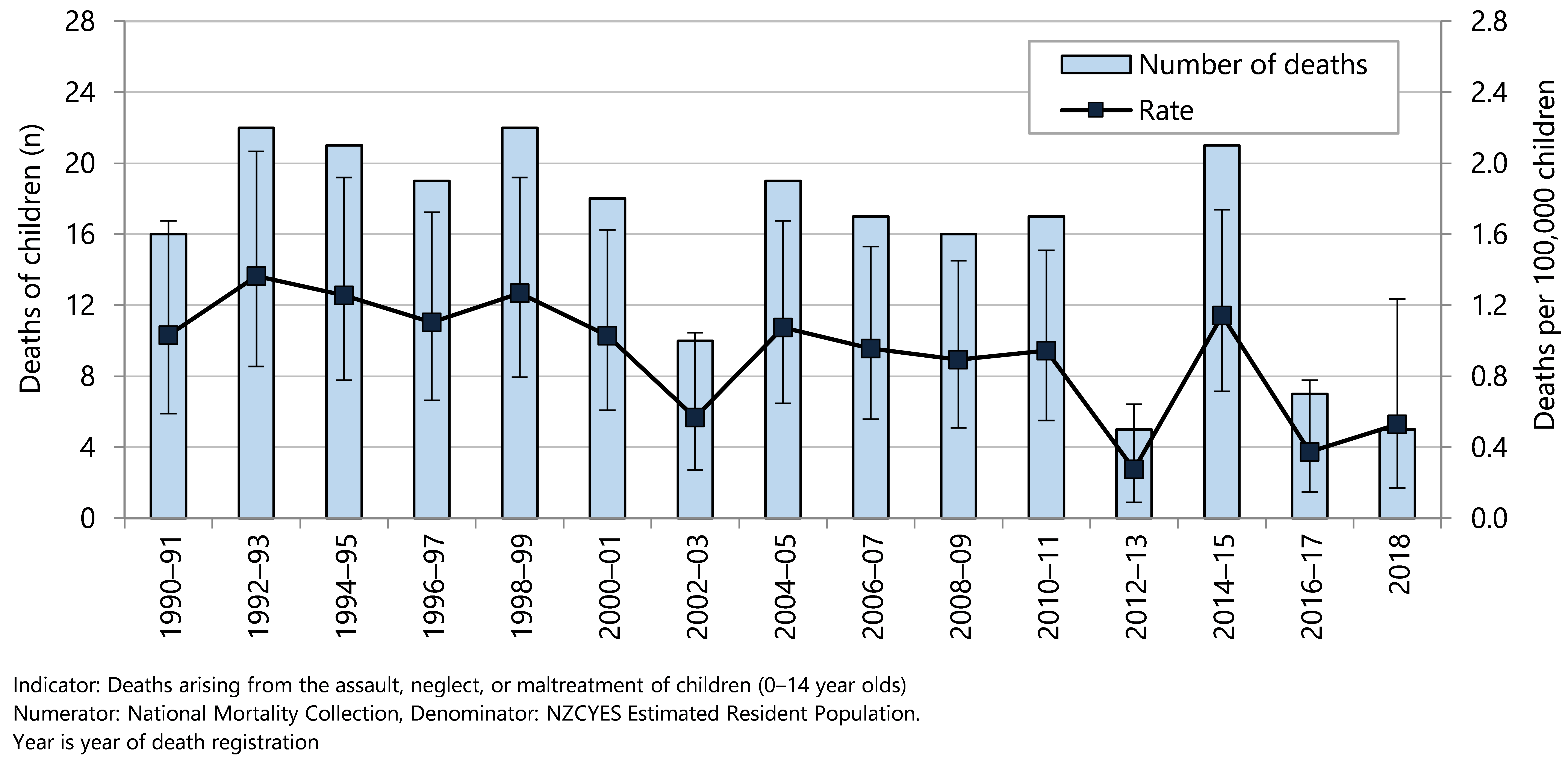

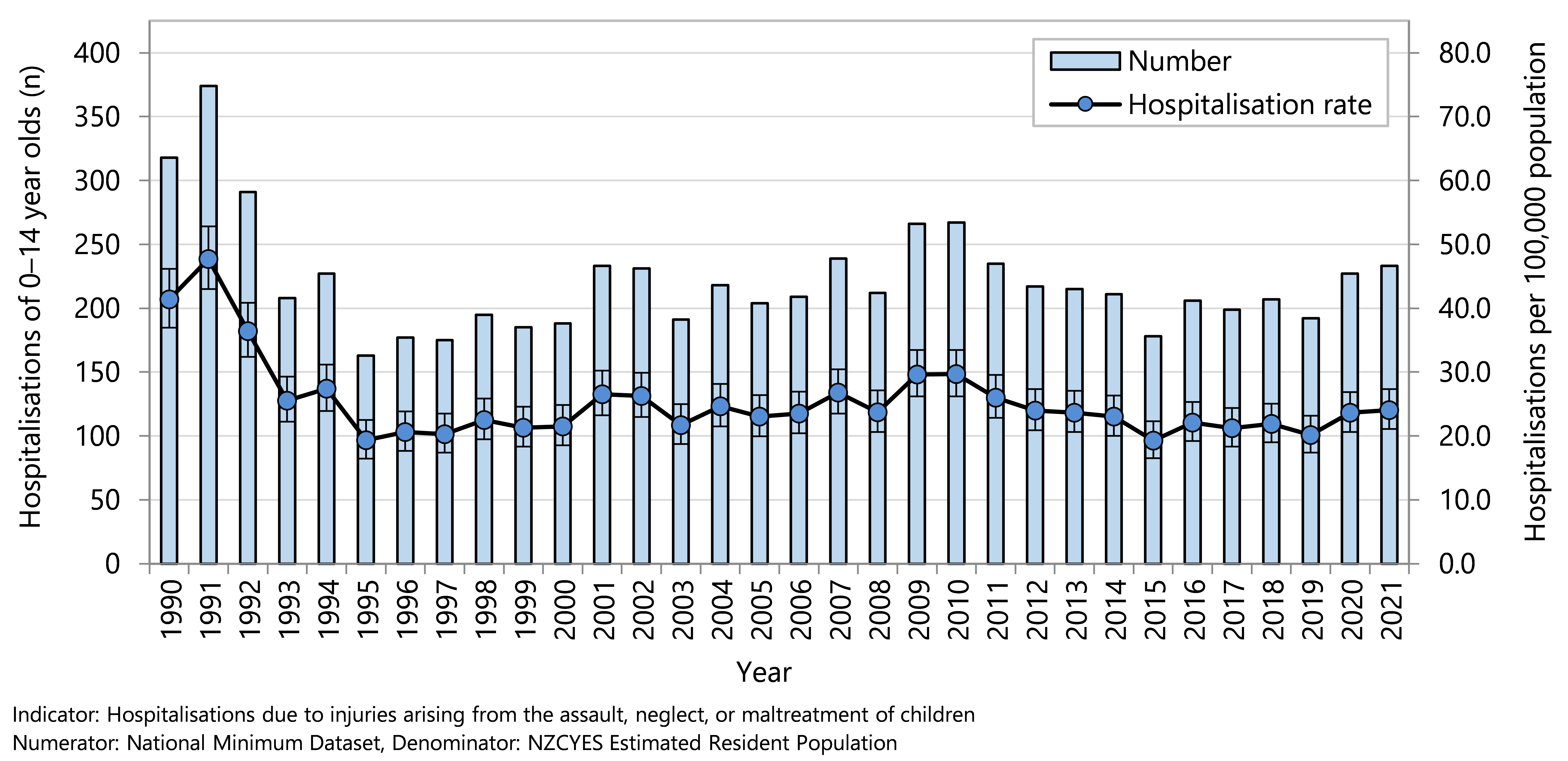

There is a lag between collection of data in national surveys and publication of the results. The child poverty statistics are based on data collection for the 2020/21 Household Economic Survey (HES) that concluded in June 2021. Data collection for the HES has been interrupted in the past two years due to the protections in place during phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most health data are presented to the end of the 2021 calendar year, but mortality data were available only to the end of the 2018 calendar year.

Expanded data collection in the household economic survey allows disaggregation of child poverty statistics by ethnicity and by disability status of the child and members of the child’s household. These analyses reveal inequity in the outcomes of measures to reduce child poverty. European children have met the population level targets for proportions living in low-income households or in households experiencing material hardship. Implementation of policies that overcome systemic disadvantage are needed to extend this achievement to all children and their households, including tamariki Māori, Pacific children and disabled children.

This report will be launched as Aotearoa, with the rest of the world, comes to the end of the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic. In May 2020 the Government Budget anticipated increases in levels of income poverty and material hardship for children in Aotearoa.5

This budget secured access to a $50 billion COVID Response and Recovery Fund. This was an unprecedented amount of stimulus for the economy to prevent and mitigate the risks of COVID-19 in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The pandemic response included easily accessible wage subsidies to try to prevent job losses. It included changes to criteria for accessing emergency grants, food bank services, and other systems that mitigate poverty.

However, some communities bore the brunt of the pandemic more than others. For example, a study found almost one in five (18%) of Pacific households lost half or more of their household income due to COVID-19.6 The impacts of the pandemic and of additional government investments cannot easily be dissected from the data in this report. Substantial investment during 2020-2021 might have masked some ongoing and underpinning factors related to poverty. Ongoing measures of child poverty among different cohorts and communities will be needed to determine long-term changes to rates of poverty throughout the population.

The foundations for Aotearoa to be the best place in the world to be a child have been set in place with the commitment of Parliament to the Child Poverty Reduction Act 20187 and the setting of Government targets, as well as in the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989 and Children’s and Young People’s Well-being Act 1989.8 No child should be left behind as Aotearoa moves to meet these targets. This report identifies actions taken within communities to overcome barriers to mokopuna, especially Māori, Pacific and disabled children, living their best lives. This is the time to be ambitious for all mokopuna, not just some, and achieve positive outcomes for all children.

All people should be able to live their best lives with all mokopuna being supported to thrive and realise their potential. Children and young people have told us that their communities and whānau are a critical factor in their wellbeing. In general, for children and young people to be well, their whānau, friends and communities must also be well. Wellbeing is about relationships, not just about having things.

“If the parents are good then the kids are good.” Rangatahi from Rotorua (What Makes a Good Life? series, Office of the Children’s Commissioner)

The stories presented in this section of the report provide examples of community-led solutions and demonstrate the importance of hearing from whānau and their communities about what works for them.

Communities / hapori provide the environments in which families / whānau / aiga live and thrive. The strength of communities is what supports families to survive and flourish. We have found, in the stories people have told us and we have read and heard, that communities hold the power to provide the best and most bespoke supports to people in their communities, in holistic and non-stigmatising ways. The Children’s Commissioner advocates for greater devolvement of funding, solutions and supports to communities – so they can decide for themselves what is needed and deliver it appropriately.

The Office of the Children’s Commissioner were supported by some key community organisations in Aotearoa New Zealand to connect to the people involved in the stories on the following pages. We acknowledge their support with thanks. (Links to these agencies are provided for information only and are current as of 1 December 2022). We also acknowledge all communities who are enabling their whānau to flourish and wish to emphasise that the stories presented here are just a few examples of the many amazing initiatives and support networks that exist across Aotearoa New Zealand.

Inspiring Communities has a strategy for ‘Child Rich Communities’ that aims to grow a movement of people who think and work in community-led ways to improve child, family and whānau well-being. It is driven by a set of principles that enable people in local places to make positive changes for themselves, their children, their family, and the wider community. They connected us with a story about Te Roopu Tiaki Rangatahi, known as Voyage, who have developed a by-rangatahi for-rangatahi programme called ‘Ko Au’ that grows wellbeing and resilience among young people.

Kore Hiakai Zero Hunger Collective brings together community, business, philanthropy, and government to increase food security in Aotearoa New Zealand. They made us aware of the Sowing Machine initiative of Healthy Families Far North, where mokopuna are supported to learn about growing kai and community space is given over to growing mara kai (gardens), thereby increasing food sufficiency in the community.

The Peter McKenzie Project supports poverty reduction through community organisations who are delivering systems-level change. These include areas such as housing, youth access to employment, wellbeing for rangatahi, and a programme called ‘Uptempo’, within Auckland Council’s The Southern Initiative. Uptempo supports Pacific peoples to improve their income potential, and interviewed aiga and their tamaiti to tell us about what they have noticed change in their homes.

St Vincent de Paul, Auckland is a story about a foodbank that was ‘taken over’ temporarily during lockdown 2020 by young people associated with St Vinnies youth programme. It has become a key community food hub.

E fofō le alamea, le

alamea (Samoan proverb) -

The solutions for our issues lie within our community

Inspiring Rangatahi to inspire rangatahi

A programme designed and delivered by rangatahi is helping young people in Porirua who have experienced challenges including intergenerational and current trauma, poverty, mental health problems and whānau breakdowns.

Called ‘Ko Au’ the programme was created by Te Roopu Tiakai Rangatahi – a leadership group developed by rangatahi with the support of four local community groups (Maraeroa Marae Health Clinic, Taeaomanino Trust, Tumai Hauora ki Porirua, and Wesley Community Action). The kaupapa for the group is to grow wellbeing and resilience among young people. They have called the journey they are on, and their group, ‘The Voyage’.

The Ko Au programme consists of facilitated workshops that support local youth to take control of their own narratives through stories they’ve seen or heard about their tupuna, ancestors, parents, whānau, teachers and peers.

The programme encourages inclusiveness, leadership, teamwork and using the participants’ strengths to support them to learn, grow and heal. The workshops are followed up with the participants to help them reflect and unpack what is happening in their lives, to create a sense of belonging and connectedness to others. Voyage members support Ko Au participants to leave the workshops with a different and more positive perspective of themselves, those around them and those who have gone before them.

The Ko Au programme is now in action in a number of places in Porirua including high schools.

“As a revolving model of co-designed ‘collaborative planning, delivery and reflective debrief’ that evolves with every workshop, it is run “By Rangatahi, For Rangatahi, With Rangatahi”. We have created an actively engaged network of safety for our young people to fall back on.”

“We see the change in their personalities and the way they carry themselves during this programme”. (Member of Voyage leadership team)

This story was brought to the Child Poverty Monitor by Inspiring Communities - a virtual organisation that promotes community-led development through providing resources, training, and consulting to community groups. It endorses Community-led Development (CLD) principles, such as growing collaborative local leadership and learning by doing, as well as an ongoing adaptive cycle of regular planning, action, reflection, and learning. They promote these principles through the Child Rich Communities framework across Aotearoa.

Read a report on Te Roopu Tiakai Rangatahi (TRTR), Voyage, and their many initiatives here

Watch a clip from a Voyage member about Ko Au here.

Read about Inspiring Communities here.

The Sowing Machine

This story is used with permission, from the July 2022 Monthly Pānui of Kore Hiakai and Healthy Families Far North. Other stories from Kore Hiakai can be found among their ‘Catalyst & Champion stories.’

Mā mua ka kite a muri, mā muri ka ora a mua.

Those who lead give sight to those

who follow,

those who follow give life to those who lead.

There is more than one way to cook a potato – and there is more than one way to create a food resilient community.

With the hurt of rising food prices and growing need for those requiring food assistance, impacting on overall community wellness, there are many champions throughout Aotearoa looking for innovative ways to strengthen their rohe.

One approach taken by Healthy Families Far North Lead Systems Innovator and former chef, Paul Condron, is to minimize reliance on supermarkets by guiding others on how to grow their own kai.

Through listening and working with whānau, Paul discovered that knowing how to grow fresh kai has become a thing of the past, and healthy kai is seen as “posh”. Paul, also known as Paora in the Far North, wants to make good kai available to all and to revitalise knowledge by teaching tamariki through play.

Through multiple workshops with whānau, and many trials, the kaupapa has taken

shape in the form of a ‘Sowing Machine' - a vending machine for growing

seedlings.

This sowing machine makes growing fresh kai a simple and fun activity, while also embedding healthy practices into the spaces where tamariki already interact and play.

Stocked with seasonal seeds, potting mix, and recycled paper cups, tamariki use the recycled cups to plant the seeds, which they can take home to their māra kai or keep in the whare kākāriki (green house) until they are ready to plant in the local community māra.

Tamariki are developing their kaitiaki of te Taiao (environmental protection) skills, so local whānau can stop in and pick up some fruit and vegetables at their local community park.

Paul said it's about making healthy kai available for all. Playgrounds are a place of learning, so why not utilize that space to teach our tamariki how to grow healthy kai, while also making healthy kai more available for the community?

“The tamariki love it and the best part is they don't feel like they're in a classroom… they’re just getting their hands dirty and having fun!” (Paul Condron, Healthy Families Far North)

Uptempo – Pasifika-led systemic change

Uptempo is an initiative focused on creating transformative change for Pasifika in Aotearoa. Uptempo’s focus is to provide learnings and insights into how Pasifika-led, workforce innovations can create the solutions needed for Pasifika people to grow and thrive. To deliver these outcomes, they work within The Southern Initiative (TSI), and alongside ‘aiga, The Fono, Oceania Career Academy and First Union.

Uptempo is supported by the Peter McKenzie Project which funds systems-changing community organisations tackling the root causes of child and whānau poverty in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Leader Anna-Jane Edwards says statistics have shown a $1.8b gap between Pasifika incomes and the rest of Auckland – that equates to about $270 per household per week.

The recent findings of MSD’s Child Poverty in NZ report, as well as evidence in this Child Poverty Monitor show that for many households, full-time paid employment on its own doesn’t provide enough income to meet even the most basic needs of a household - especially where there are children.

Anna-Jane says the problem needs a systemic approach – that working family by family will not reach the scale needed.

Uptempo achieves this by working with government, social agencies and employers to create sustainable, intergenerational wealth for Pasifika. They work with ‘aiga to develop their skills, grow their networks, and access holistic support to meet their needs and aspirations, so Pasifika are leading their own futures.

They also work with employers to help them become more culturally responsive workplaces that respect, uphold and nurture Pasifika values.

At the same time, they work across communities to strengthen connections, celebrate Pasifika values, build partnerships and promote positive Pasifika stories.

Their work helps Pasifika to pursue learning, training and employment opportunities that will help them reach their family goals.

All of the learning from working alongside 'aiga, training providers, employers and community, are packaged and shared with government to create scale by informing policy, commissioning, and designing future activities in Pasifika communities.

The experiences reported by Pasifika families working with Uptempo shows it is working.

We heard about one family who immigrated just as Covid hit and were struggling to cope. Through working with Uptempo both parents have taken up training and work opportunities, the children are at school, and they are all engaging with their community. The mum says: “We just needed a little support and direction, the rest we can do for ourselves.”

Another family were juggling the responsibilities of fulltime work and five children. Through their involvement in Uptempo they became more connected to their community, introducing more families to the group and helping them connect to new opportunities. The process has also led the family themselves to learning opportunities and better leadership skills which has helped them into higher paid jobs that will enable them and their children to live lives of dignity and thrive across multiple generations.

A third family of a sole parent and six children were living on one low wage, while the parent was also trying to up-skill to improve the whole family’s prospects. Uptempo helped her get all the government support she was entitled to, and also helped her connect to the community for support. She has now moved into full time work in education and is helping other Pasifika families improve their prospects.

Below are some quotes from Pasifika children who told Uptempo about changes they have already noticed, and that these changes will mean some of their dreams for themselves and their families can come true:

“My mum and dad going to training they know about internet. They are happy all the time.”

“My mum and dad would buy our own house and my mum would do some shopping on clothes.”

“Enjoy having dinner with my whole family.”

“Buy the car and get a house.”

(Children in ‘aiga involved with Uptempo, who drew the pictures.)

Heads, Hearts and Hands

There’s a saying “doing good does you good” – and the young people of Auckland Vinnies, are proving the truth of that saying, with their work to support those doing it tough in their local community.

St Vinnies, which is formally known as the Society of St Vincent de Paul, is a Catholic faith-based, international organisation. The Vinnies Hub in Onehunga houses the Vinnies Auckland youth team that runs school programmes across Auckland. It also houses a large foodhub and advocacy centre that supports families across Auckland.

Young people have always been involved in the Vinnies hub, but challenges presented by COVID meant they felt they really had to step up.

During the first lock down in 2020 the Vinnies hub made the decision to keep the doors open, and recruit family ‘bubbles’ to do all the processing and packing of food parcels. They called on their community – and the community responded, mainly in the form of young people.

As one young Pasefika woman explained “We figured we were all healthy, and Mum and my sister couldn’t work in lockdown, and I was a student – so we just had to. Other families couldn’t because they had immunocompromised people living with them.”

This young woman had already been volunteering at the foodbank - so knew all the systems there and was able to support her mother and three older siblings to put their values and their faith into action to become part of the solution.

Having weathered the first lockdown the new and improved Vinnies hub was well set up to deal with the extended Auckland lockdown in 2021, increasing their distribution of food parcels from about 70 a week to reach 1800 referrals for food per week. In the process this provided the young people helping out with an opportunity to build their own mana, by witnessing the need and then working to help others who were doing it tough in their community.

For one young man, starting as a driver meant he saw firsthand the hardship people faced in run-down, often crowded, homes. The experience opened his eyes to others’ situations and he recognised they really needed the support. He became part of the Vinnies youth programme which visits schools to raise awareness of key aspects of poverty: social exclusion, food insecurity and homelessness.

Under the school programme students collect non-perishable foods for the food bank, visit the food banks and do cooking after school.

As one Year 13 student said he’d learned that food insecurity is a multi-faceted problem which “comes in different shapes and sizes, you don’t know who is affected. People are too shy to talk about their struggles. We need to accept everyone as they are with open arms and treat everyone with respect.”

The combination of education and volunteering – heads, hearts and hands – is what changes the lives of young people and the communities they support. The education provided by Vinnies along with the real world experience means students “understand the deeper meaning of poverty and how it impacts people in our communities. Teaching rangatahi helps them teach others around them. We have a lot of Māori and Pacific peoples around here, and our backgrounds have oral traditions. Word of mouth is a big way of teaching others empathy” (year 12 female student, Vinnies School leader and volunteer).

There is also a skills development aspect – the young people learn leadership skills, develop strong relationships in their communities and “establish a ‘giving’ habit.” (year 13 male student, Vinnies youth leader). It is “stressful but powerful. I had a sense of myself being moulded through being exposed to people in need. It shifts your perspective in life going forward. I can understand the mana and dignity that other people hold.” (Female graduate, Vinnies School leader and volunteer).

“I have a busy life with study but this is an investment in myself and leaving a legacy - you’re changing the world where it’s needed.” (Male university student, Vinnies Tuakana leader)

Key points

Ending child poverty

At a national level there has been progress toward the child poverty reduction targets set by Government as required in the Child Poverty Reduction Act 2018. When data are disaggregated by ethnicity or by disability status it becomes clear that we need strong decisive action so that all children and young people enjoy equal opportunity to thrive and do well. Many children growing up in households with very low income or material hardship experience love and support from their whānau, families and aiga around them. This does not overcome the association between measures of child poverty and adverse outcomes with potential negative long-term impacts.

In the 2021/22, for children aged under 18 years:

-

Using the fixed-line measure of equivalised disposable income after housing costs below 50% of the 2017/18 median, all groups of children have met the 2020/21 target of 18.8% and European children have already met the 2023/24 target of 15%. The target for 2027/28 is 10%. Overall, approximately 187,300 children (16.3%) still live in households below this poverty line and a gap remains between European children and those identifying with other ethnic groups, and between disabled children and non-disabled children. (European children 14.1%; tamariki Māori 17.8%; Pacific children 16.3%. Disabled children 17.6%; non-disabled children 16.2%).

-

The target of 10.5% of children living in households with equivalised disposable income before housing costs below 50% of the contemporary median was not met overall in the 2020/21 survey year, with around 156,700 children (13.6%) in this category. The target for 2027/28 is 5%. The advantage enjoyed by European children means they were the only population group to have met this target, and European children also met the 2022/23 target of 10%. (European children 9.7%; tamariki Māori 18.1%; Pacific children 17.2%. Disabled children 15.5%; non-disabled children 13.7%).

-

The 2020/21 target of 10.3% of children living in households experiencing material hardship was met when the sampling error was taken into account, with 125,700 (10.0%–12.0%) experiencing a lack of six or more essentials. The target for 2027/28 is 6%. Material hardship decreased for all groups of children between 2019/20 and 2020/21, with a persistent high level of disparity between population groups. The 2020/21 and 2022/23 targets (9.0%) were met for European and non-disabled children. (European children 7.8%; tamariki Māori 20.2%; Pacific children 24%. Disabled children 20.5%; non-disabled children 9.7%).

Health

Access to primary care

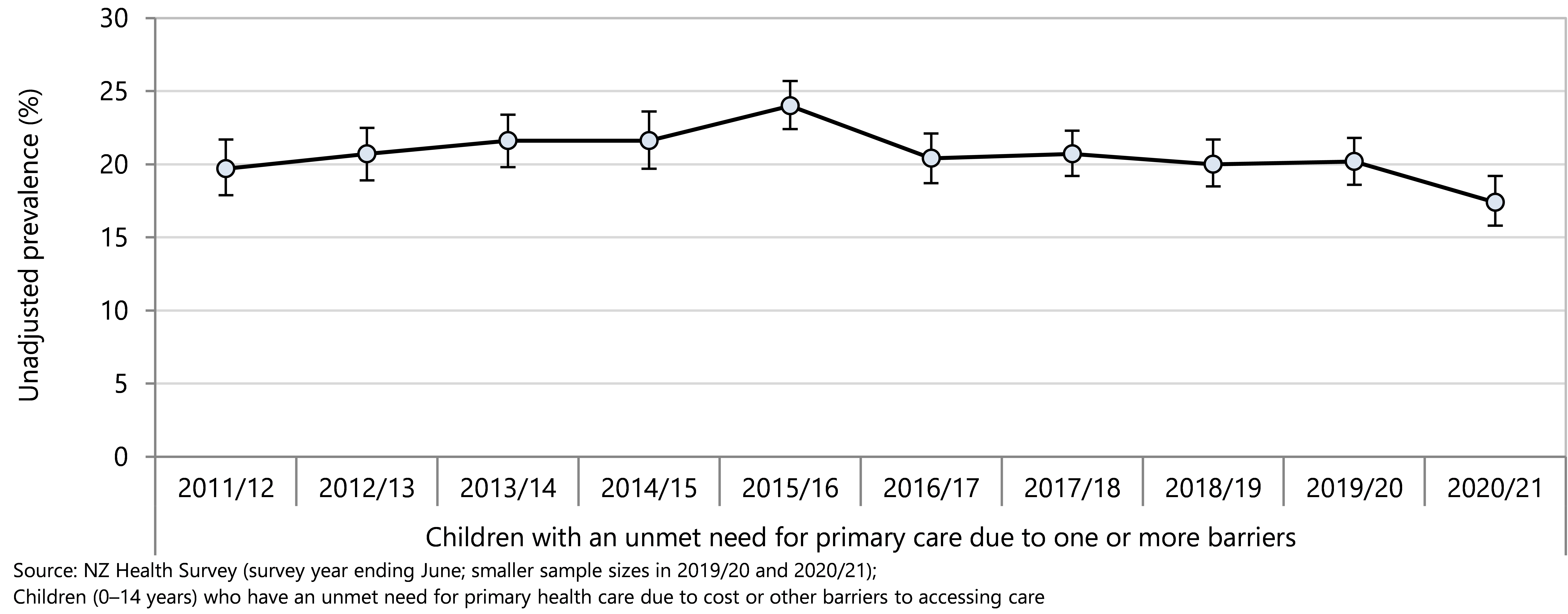

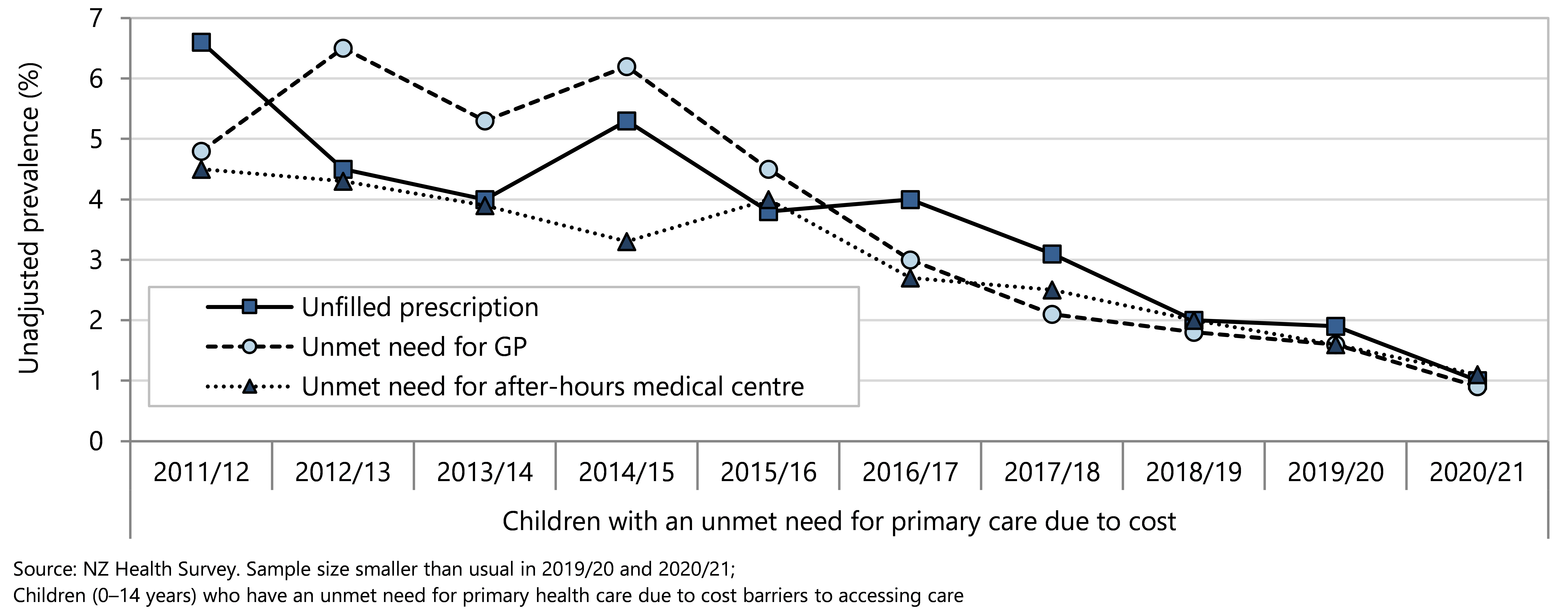

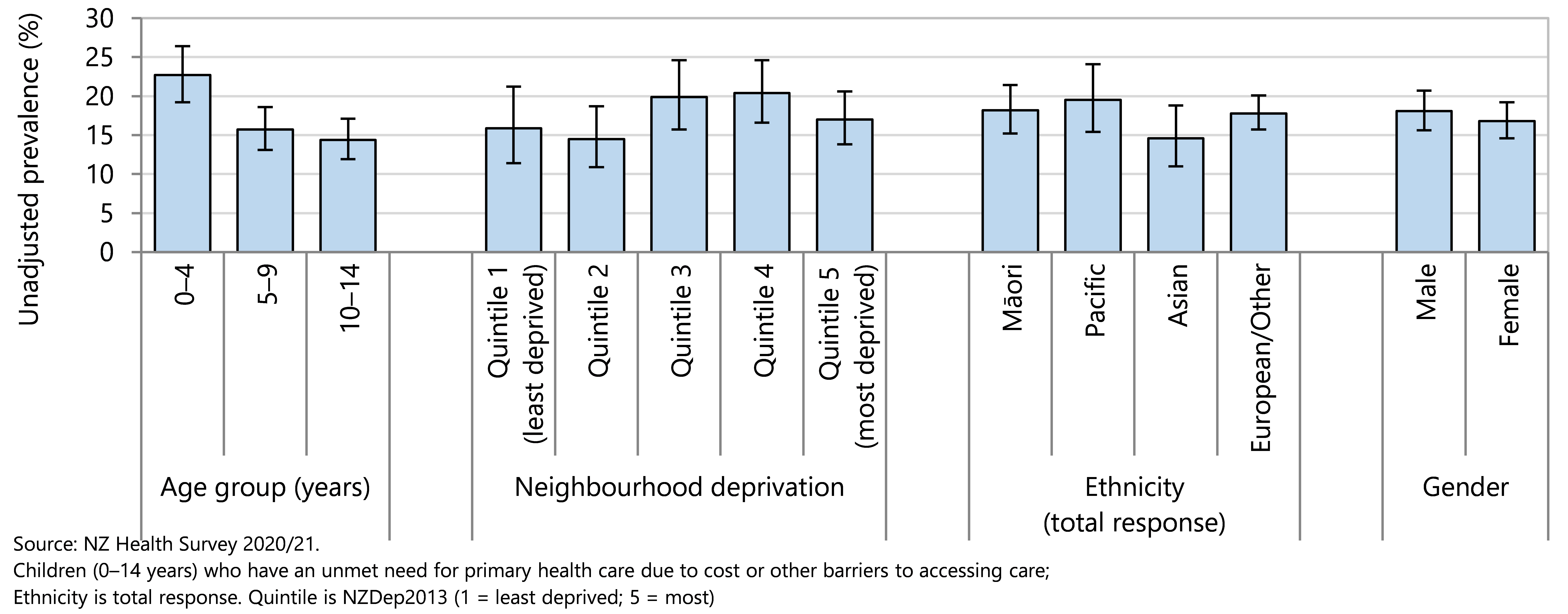

Government initiatives have significantly reduced cost as a barrier to children accessing primary care when they have a medical problem needing attention. In 2020/21 almost two-thirds of children (64.5%) had visited or talked with a GP in the previous 12 months.

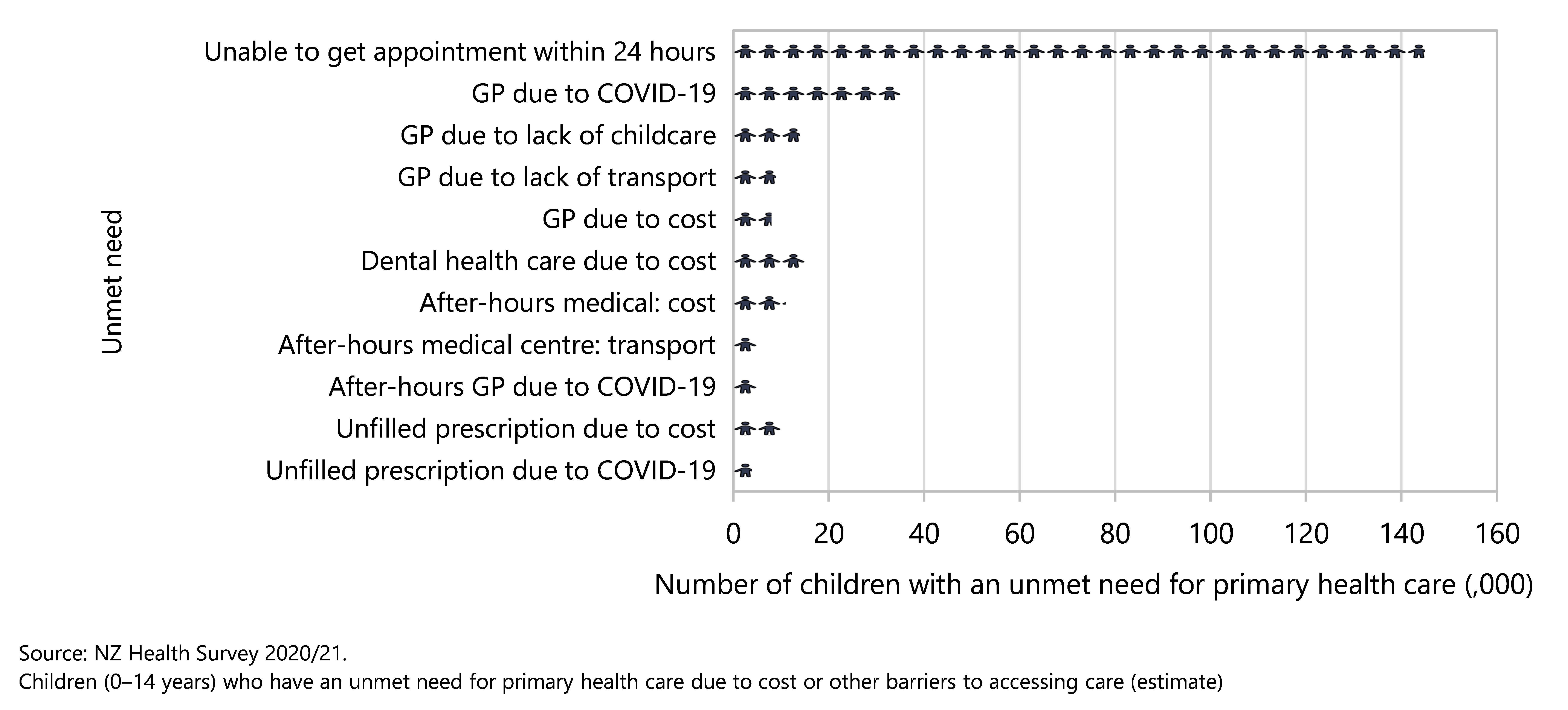

The most frequent barrier to accessing primary care in 2020/21 was the inability to make an appointment within 24 hours. Around 145,000 children were unable to get an appointment within 24 hours when they needed it. This barrier affected children in all population groups.

COVID-19 was a barrier to 35,000 children accessing GP care when they needed it; barriers related to the pandemic could include fear of being infected, pandemic restrictions, not wanting to have a virtual consultation, or other concerns.

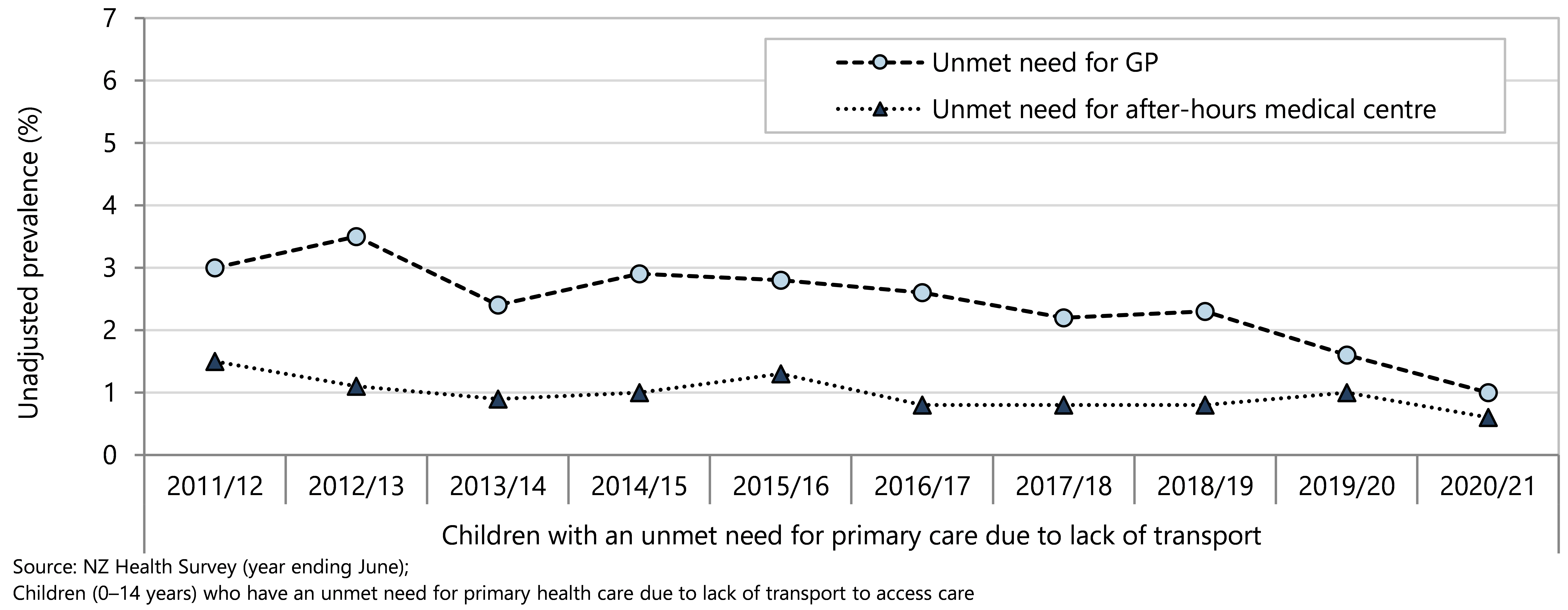

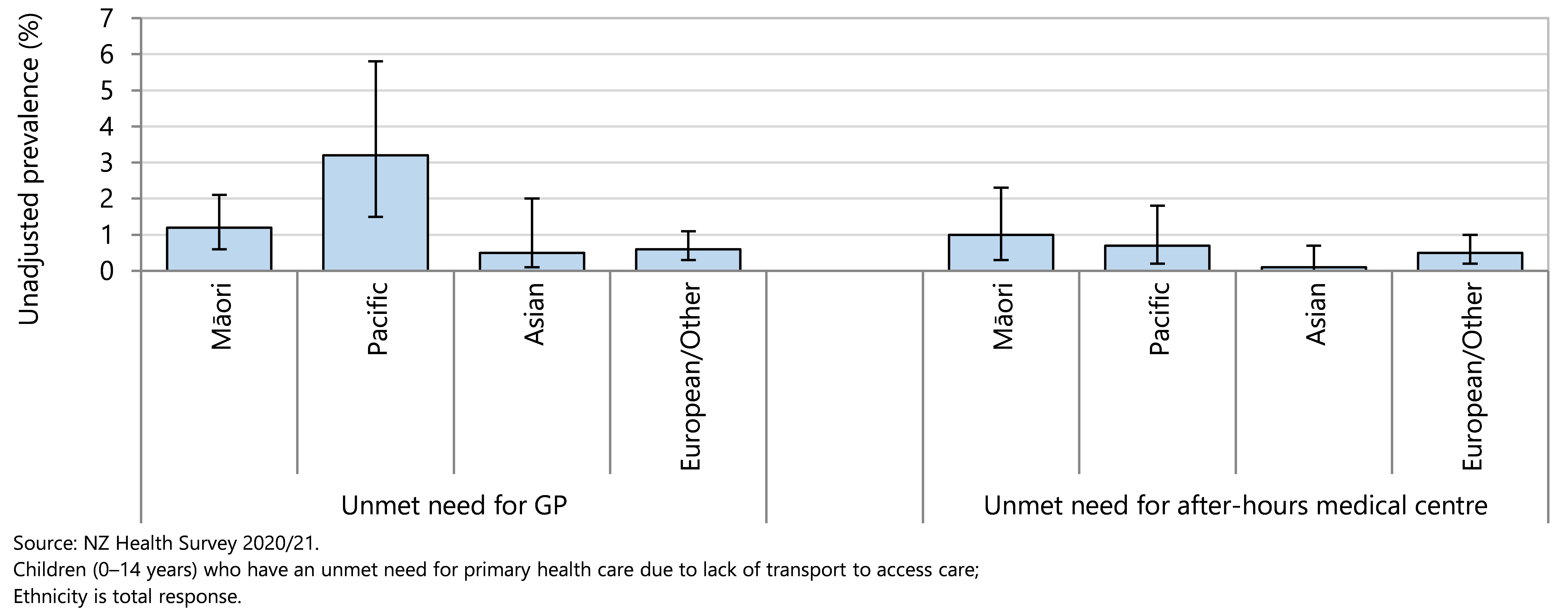

Lack of transport and lack of childcare for other children remain barriers to primary care for around 9,000 and 14,000 children respectively.

Immunisation

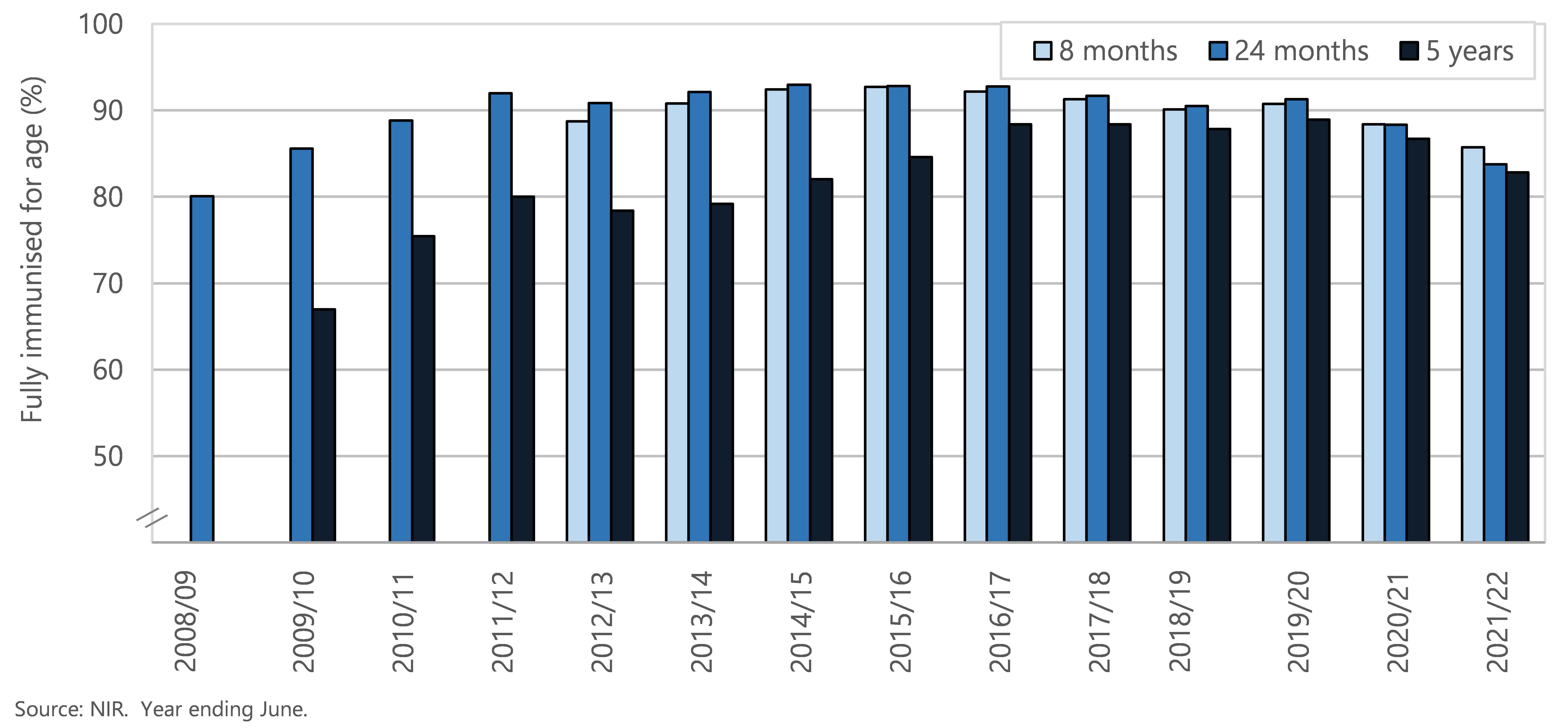

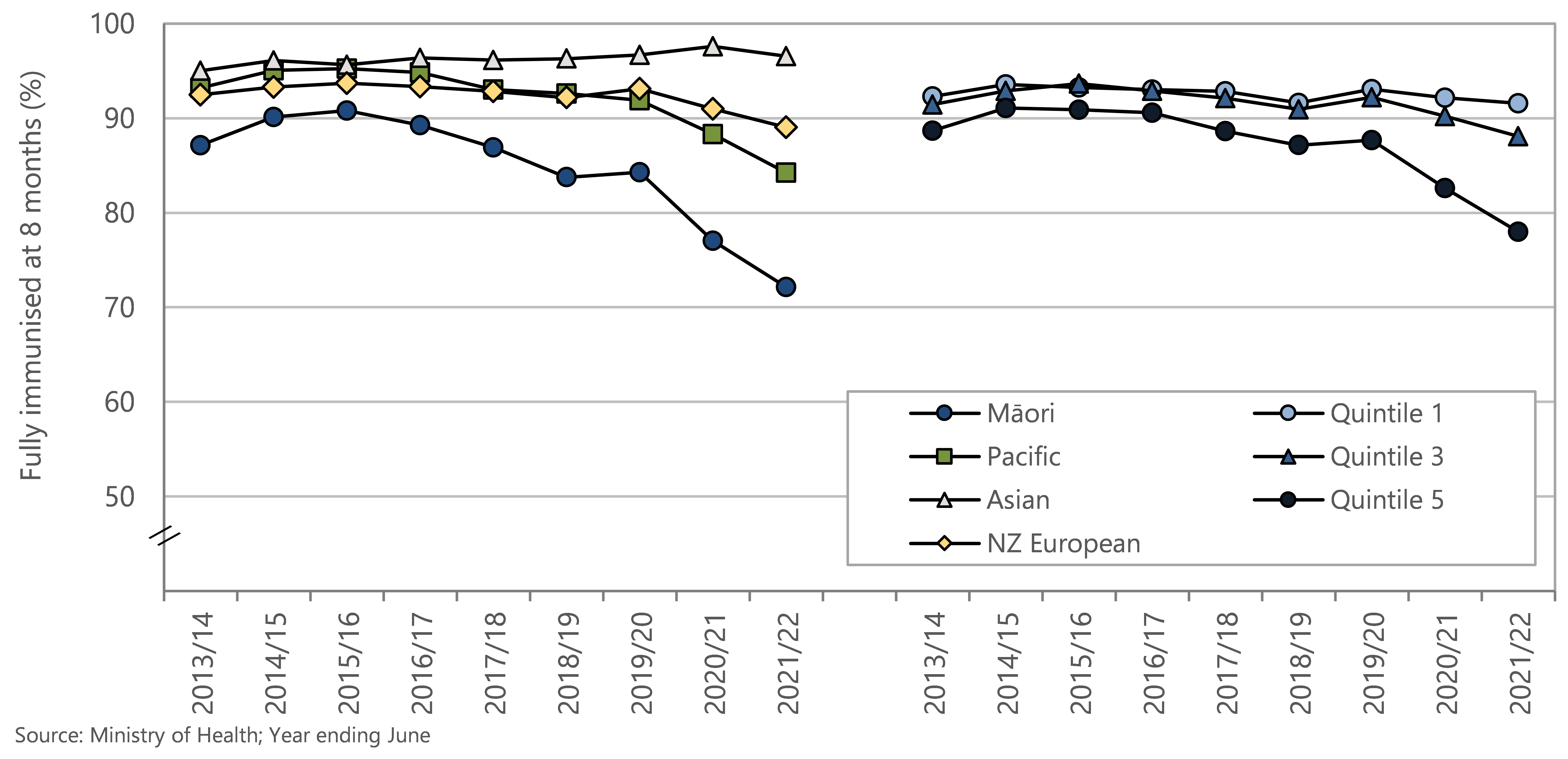

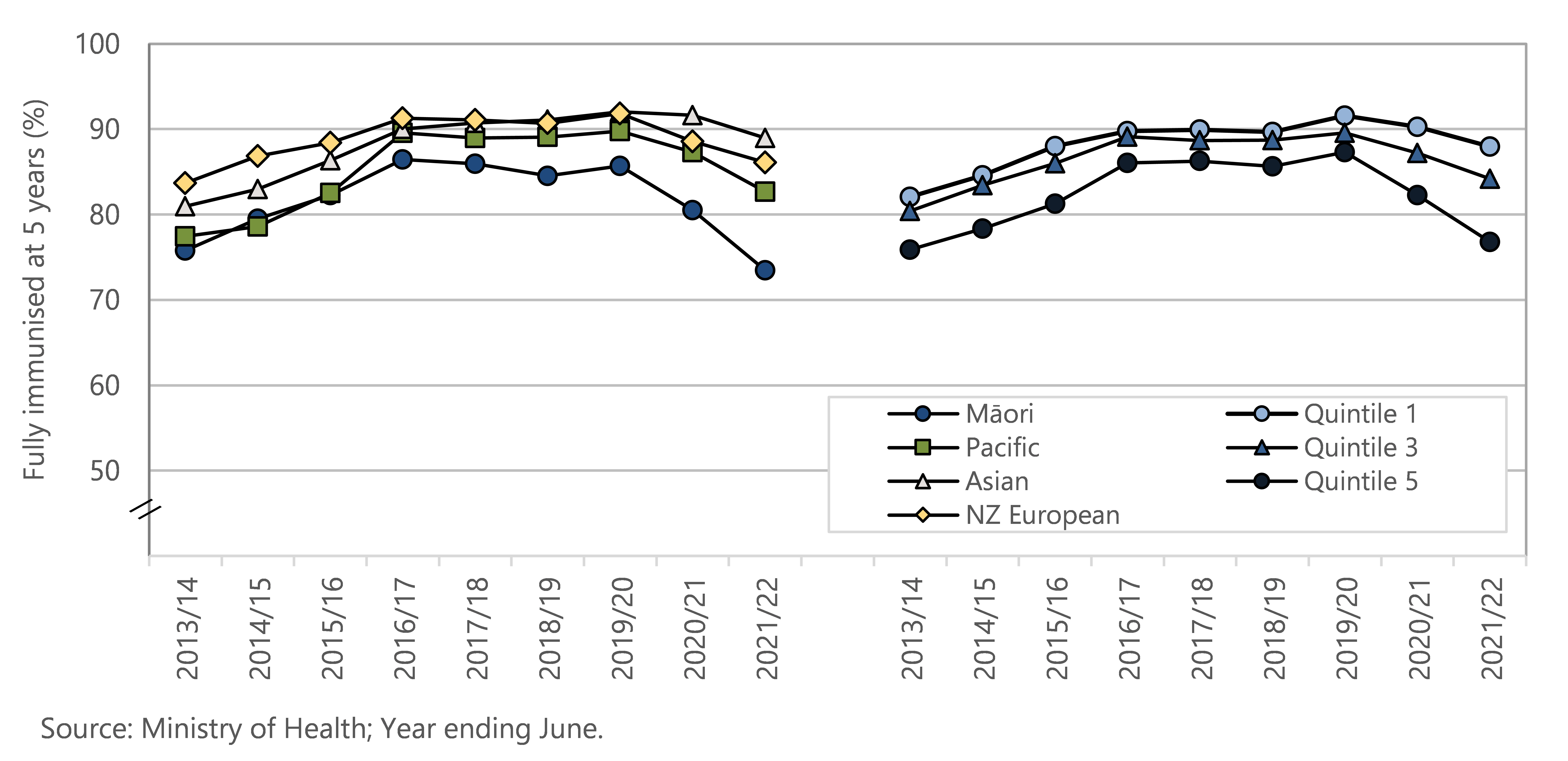

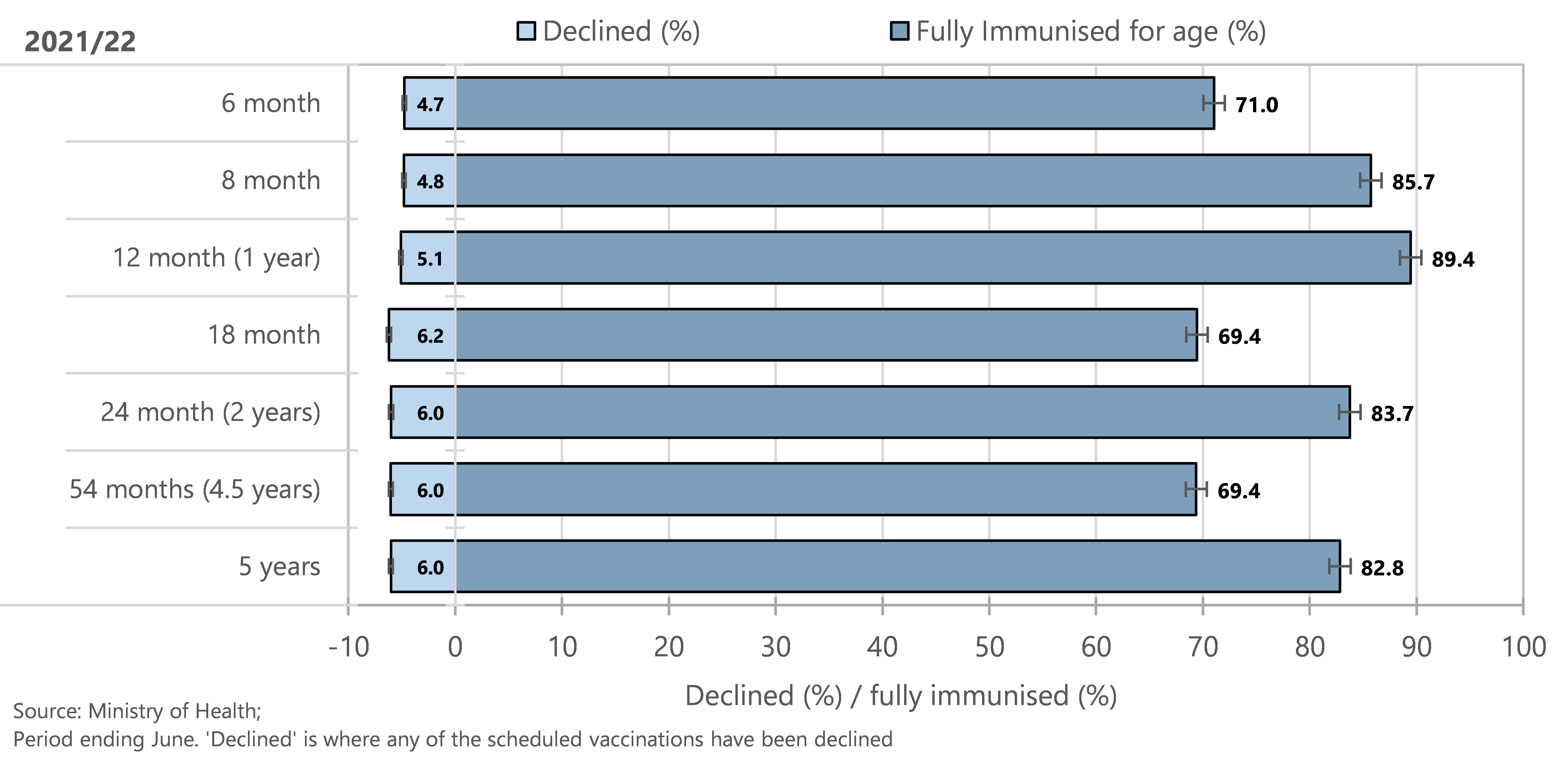

Immunisation rates have fallen well below the target of 95% needed for a protected community. In 2020/21 only 85.7% of all babies were fully immunised at age 8 months, with 84.2% of Pacific babies and 72.1% of Māori pēpi fully vaccinated at this age.

The proportion of 8-month-olds fully immunised in areas with high deprivation scores on the New Zealand index of deprivation (NZDep) has been consistently lower than the proportion in less deprived areas. This gap based on deprivation level increased markedly from 2016/17 to 2021/22.

Children in Aotearoa are now less protected from vaccine-preventable disease than they were before the COVID-19 pandemic. There is an urgent need to prioritise childhood vaccinations and to overturn the inequity in vaccine delivery that has increased markedly during the pandemic and response.

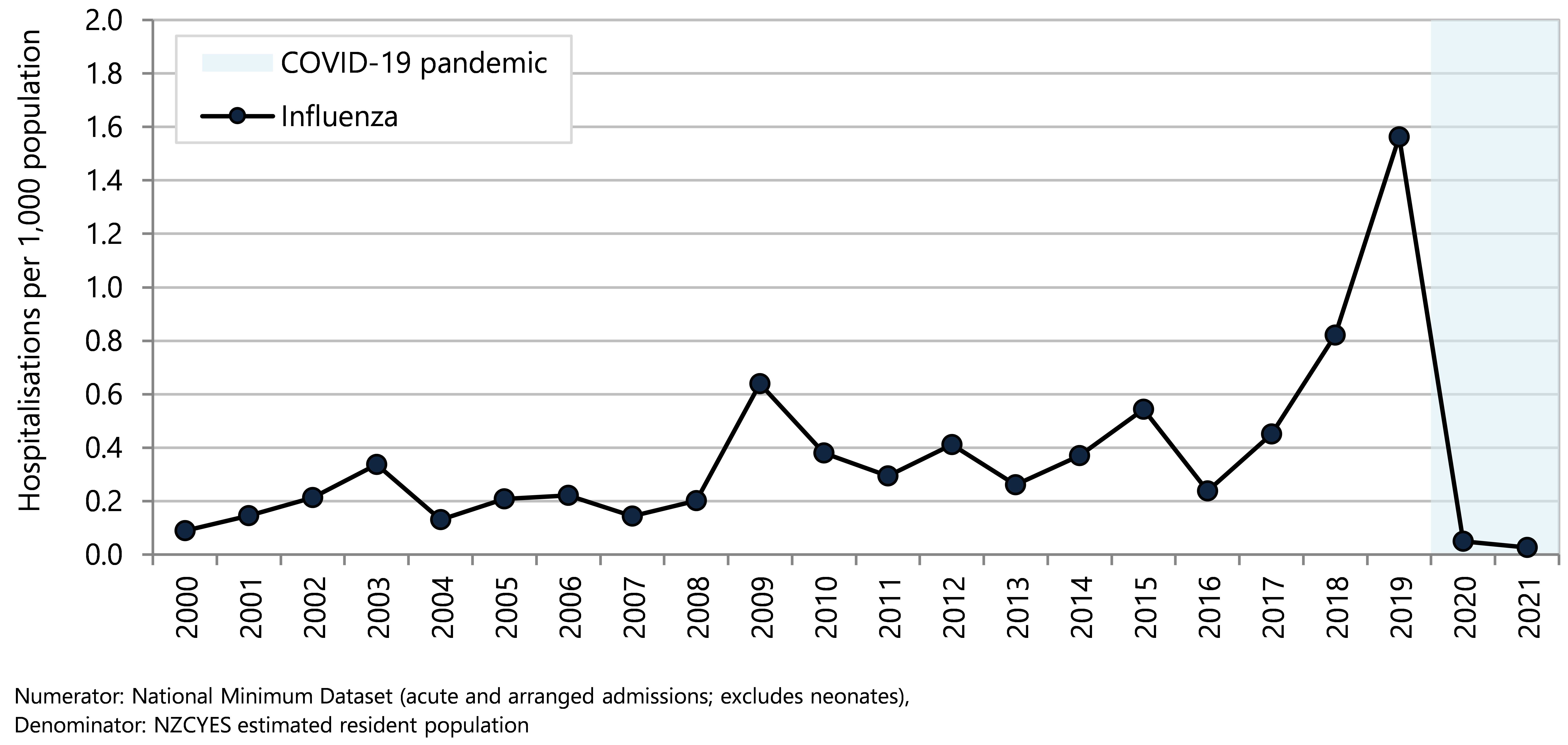

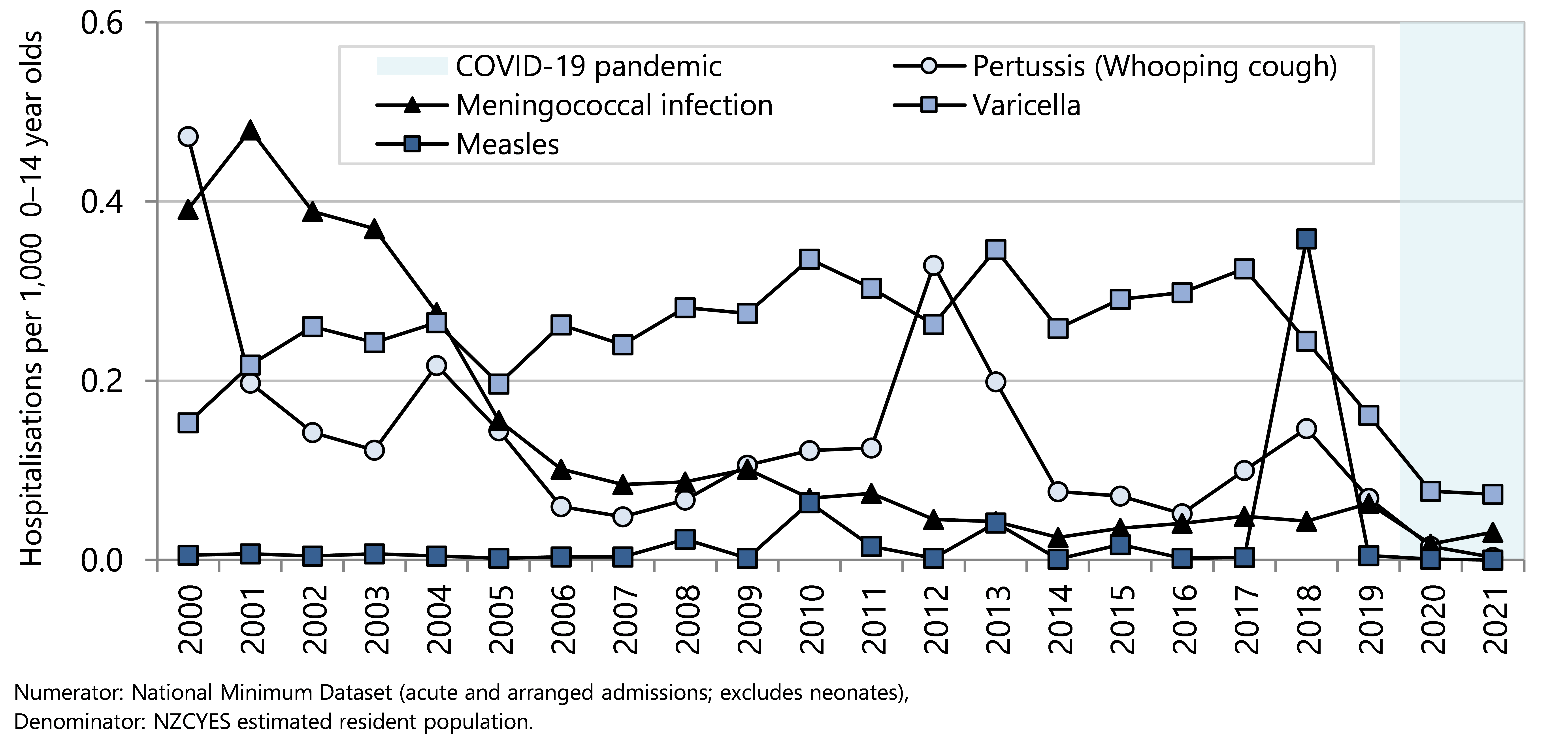

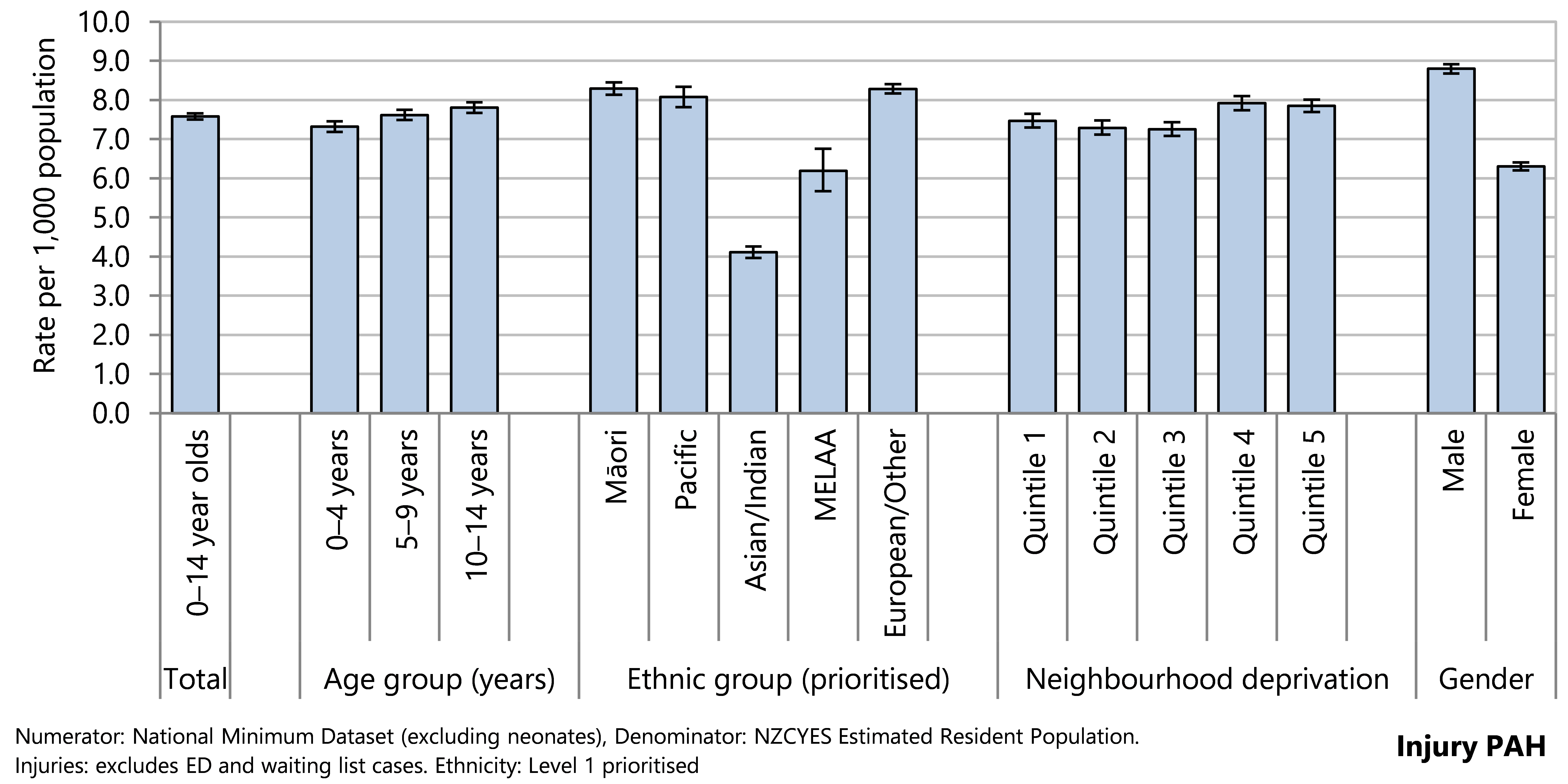

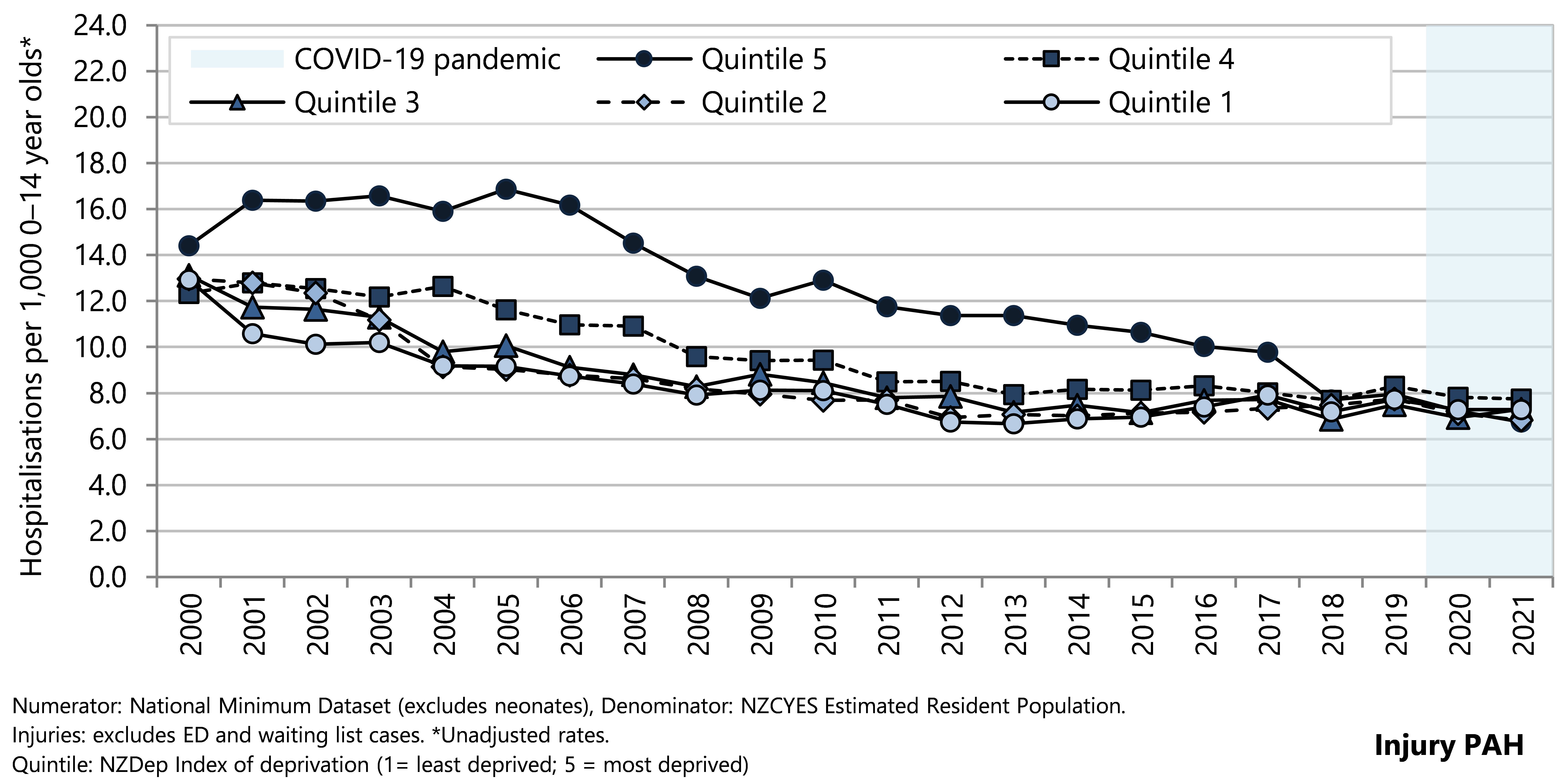

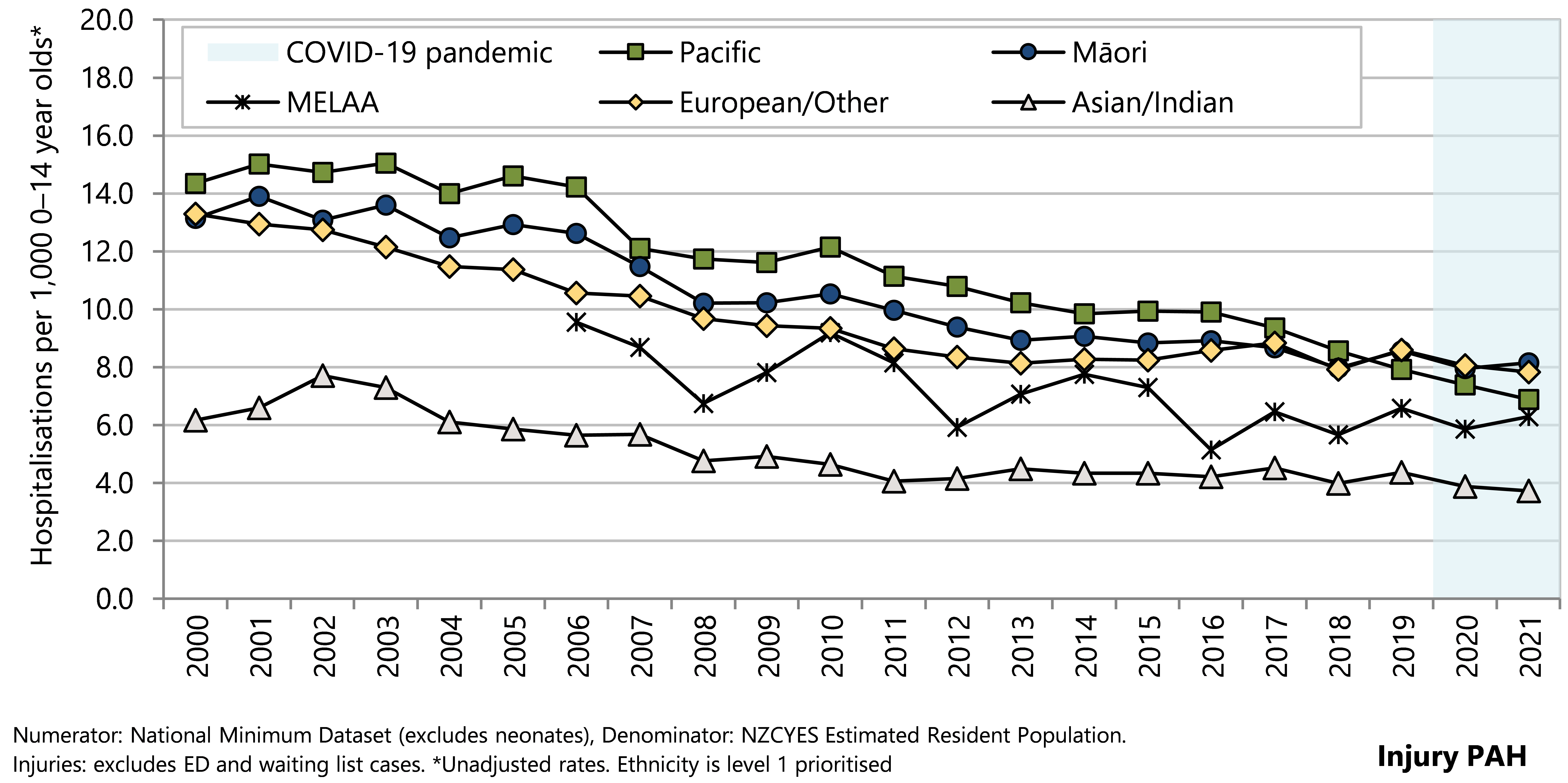

Vaccine preventable diseases

From 2017–2021 there were almost 5,000 potentially avoidable hospitalisations for vaccine preventable diseases. Hospitalisation rates for all common VPD declined sharply in 2020 and stayed low in 2021. The fall in vaccination rates raises concerns about the ongoing potential for further outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.

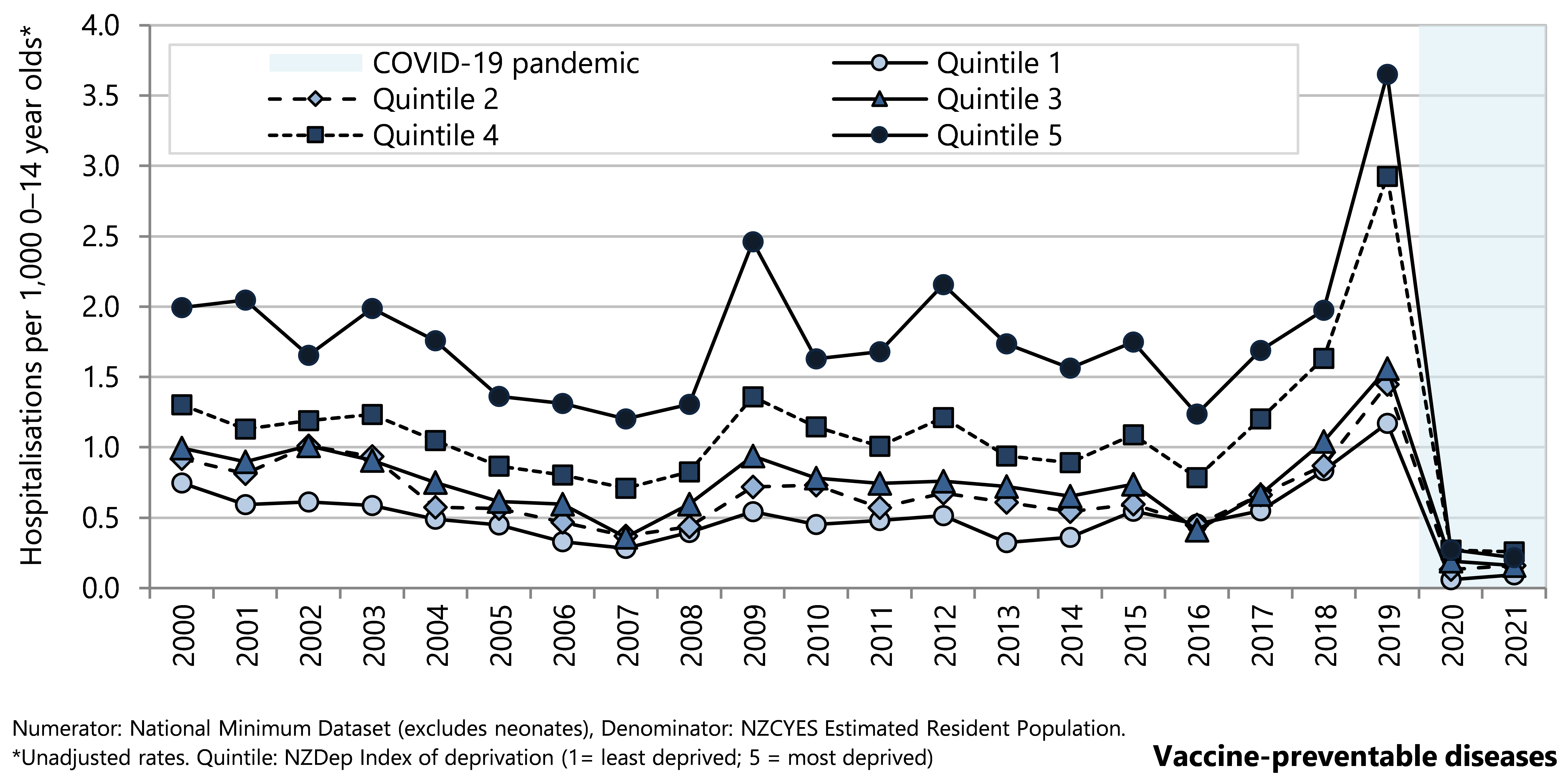

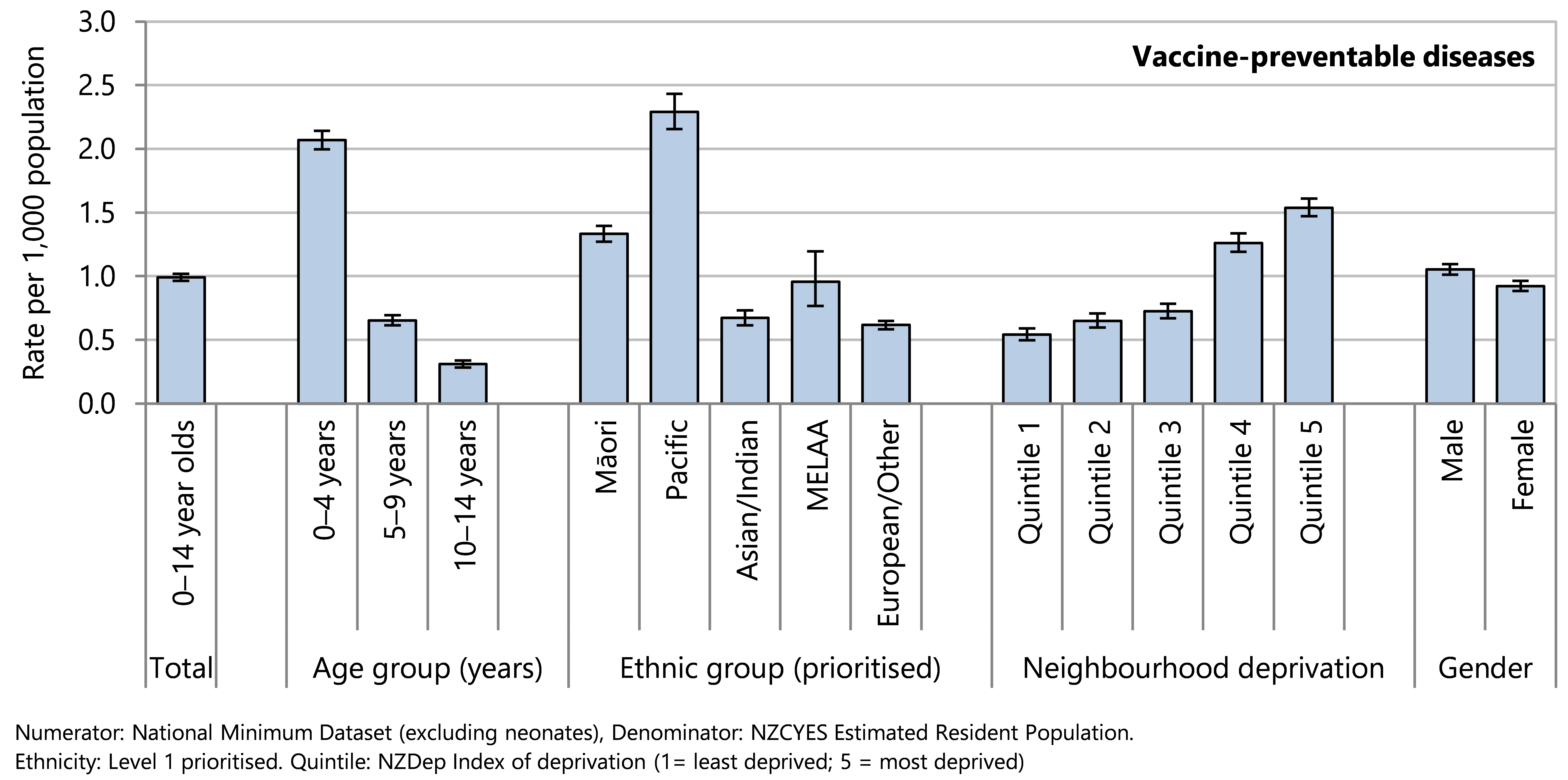

Some children were better protected than others from vaccine-preventable illness serious enough to need hospital treatment. Children living in the most deprived neighbourhoods (NZDep quintile 5) had a hospitalisation rate for vaccine-preventable diseases that was almost three times as high as the rate for children living in the least deprived neighbourhoods (NZDep quintile 1).

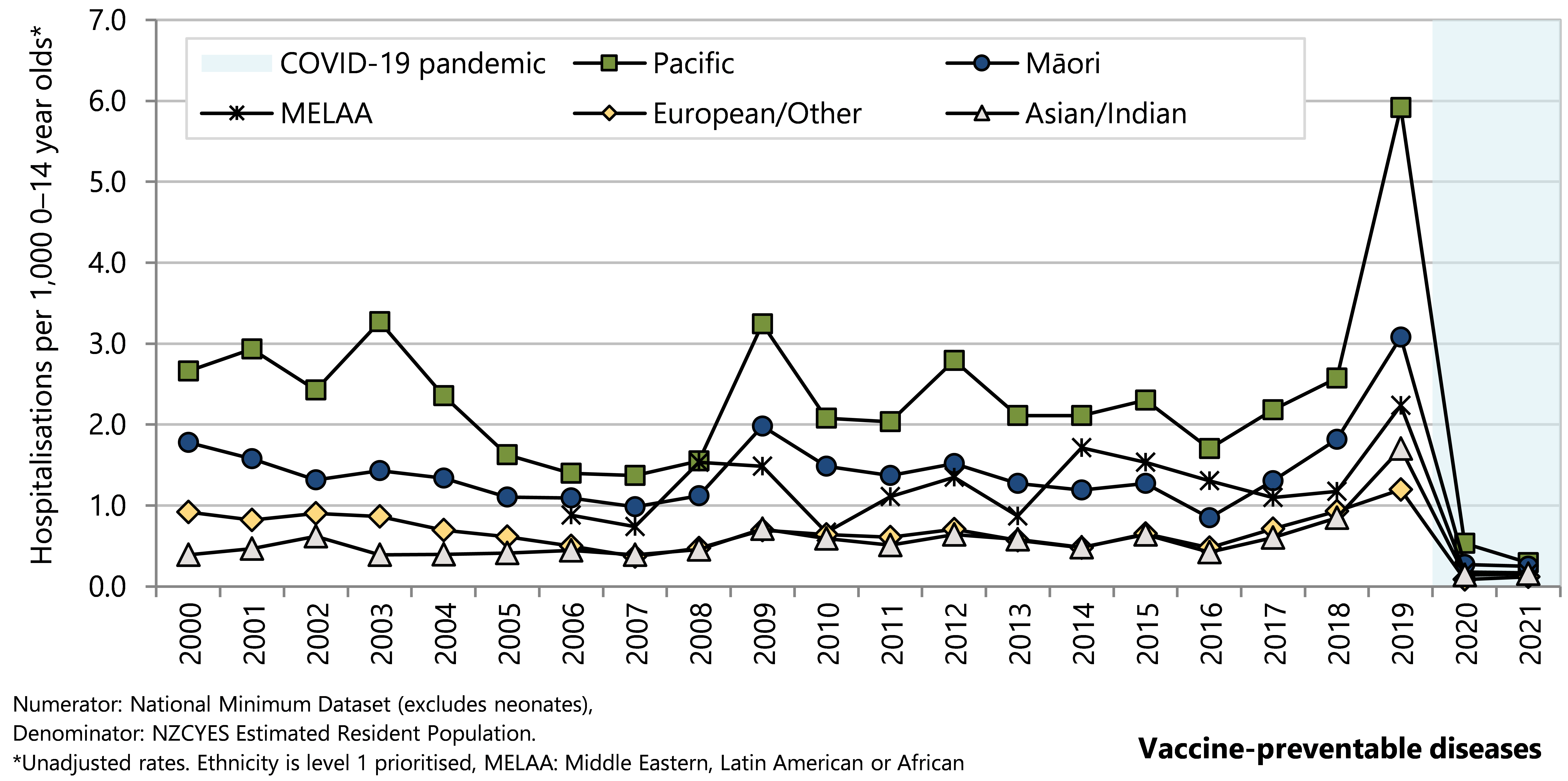

Pacific children had the least protection with a hospitalisation rate for vaccine-preventable diseases almost four times as high as rates for European/Other and Asian/Indian children. The hospitalisation rate for vaccine-preventable diseases for Māori children was twice as high as the rates for European/Other and Asian/Indian children.

Food security

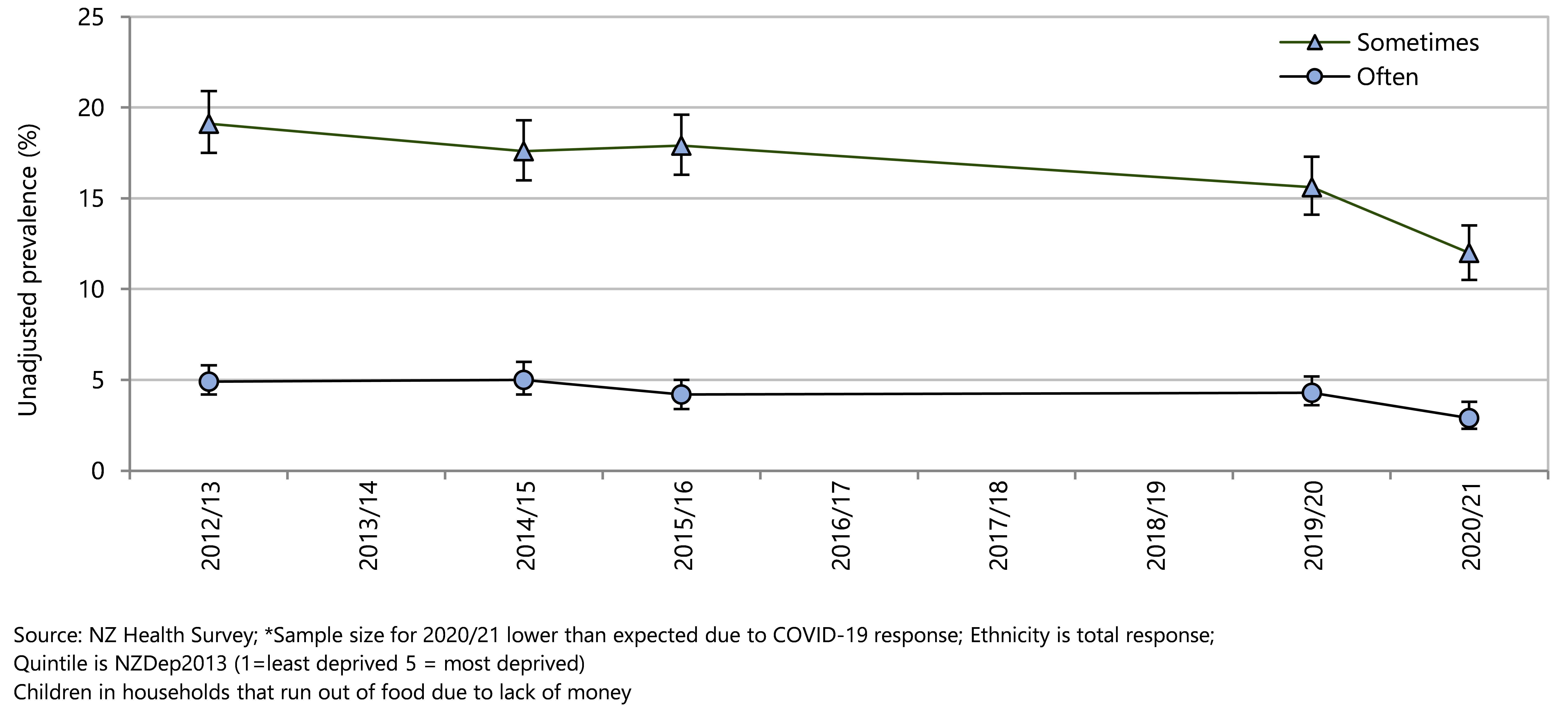

In 2020/21, around one in six children (14.9%) were living in households where food ran out sometimes or often due to lack of money.

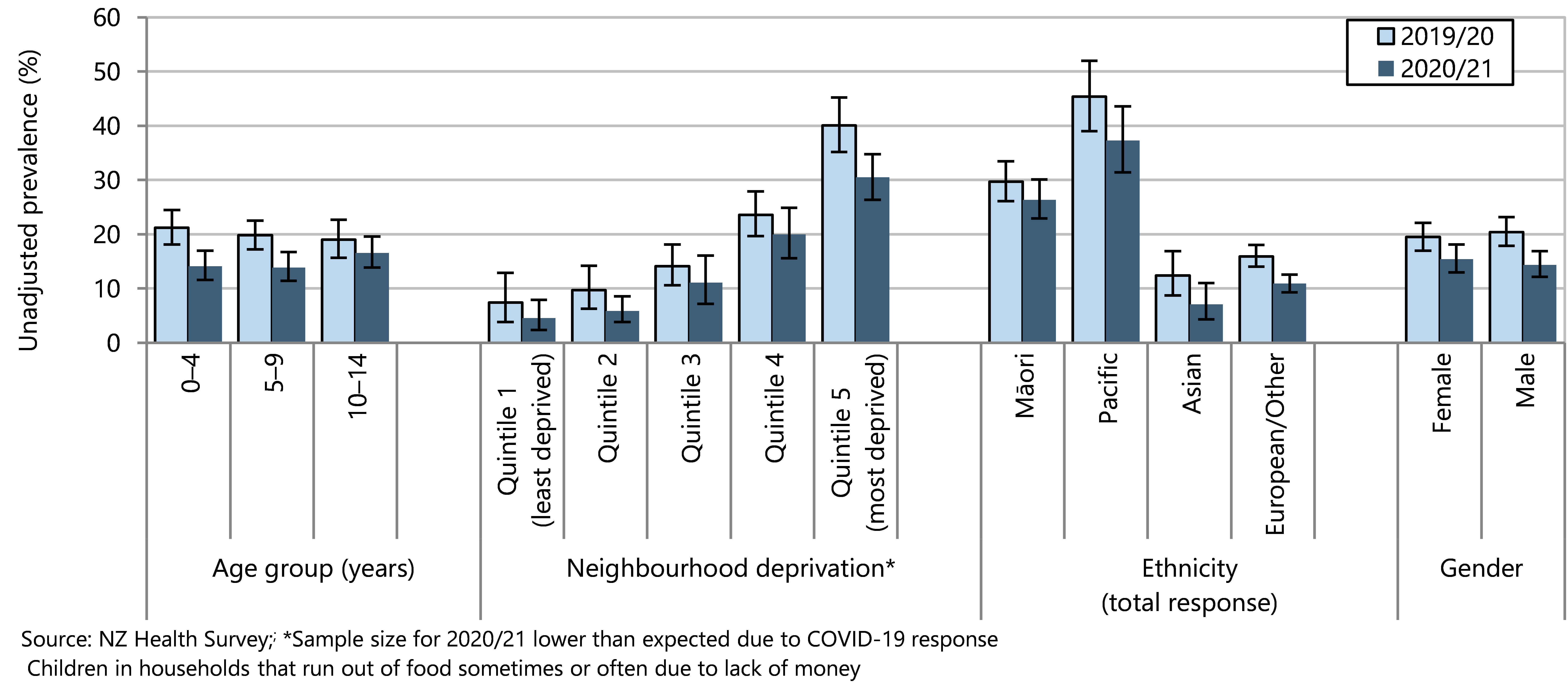

A higher proportion of children living in areas with the highest deprivation scores (NZDep quintile 5) lived in households that sometimes or often ran out of food due to lack of money, compared with 4.6% of children living in neighbourhoods with the lowest NZDep scores (Quintile 1).

Over one-third of Pacific children (37.3%) and 26.4% of Māori children lived in households that sometimes or often ran out of food. European children were better protected from inadequate nutrition, with 10.9% living in households that sometimes or often ran out of food.

A place to call home

Affordable homes

Housing is classified as unaffordable when households spend more than 30% of disposable income on housing costs, which includes rates, dwelling insurance, mortgage and rent. For the year ending 30 June 2021, 34% of all households with children aged 0–17 years spent more than 30% of their disposable income on housing.

Housing unaffordability disproportionately affects lower income households.

Approximately 60% of households with children in quintile 1 (lowest 20% of income distribution) spend more than 30% of their disposable income on housing, compared to only 11% of children in households in the top 20% of income distribution (quintile 5). More than one in three quintile 1 households with children spend more than 50% of their disposable income on housing costs.

More than 40% of households with children who are renting spend more than 30% of their income on housing costs. Quintile 1 households with children who pay private rent and receive the Accommodation supplement payment spend close to 50% of their income on housing.

More than half of all single-parent households spend more than 30% of income on housing, and over one in five single-parent households have housing costs of more than 50% of their disposable income.

Healthy homes

Healthy homes protect children and their whānau from communicable disease transmission and other health problems. In 2020/21, 6% of children aged 0–17 years lived in households with major problems with dampness or mould (down from 9% of households in 2017/18).

Poor quality housing disproportionately affects children in low income households (10% of children in quintile 1 households), children of Māori (10%) and Pacific (12%) ethnicity.

Ten percent of households with a child with a disability or households with a disabled person live in poor quality housing.

Major problems with dampness and mould are reported by 11% of households who live in rented accommodation compared with 2% in owner-occupied homes.

Household crowding

Children need adequate shelter, space, and privacy within their homes, taking account of the number of people living there. Reducing household crowding is an important intervention to reduce the high rates of hospitalisation for infectious diseases among children in Aotearoa.

In each census year since 1991 there have consistently been 16% or 17% of New Zealand children aged under-15 years living in crowded households, including around 5% of children living in severely crowded households.

The highest levels of household crowding were experienced by Pacific children, over 40% of whom lived in crowded households including 18% who lived in homes with severe crowding.p>

Over one-fifth of tamariki Māori lived in crowded households (23.5%). This group includes 9% of Māori children who were living in severely crowded households (17,410 children).

Ending child poverty

Adequate income

Adequate disposable household income is important to provide children with the necessities of living, and the opportunities to participate fully in society. A household with sufficient income is better equipped to provide the nurturing and enriching relationships that are critical to children’s growth and development.9,10,11

To measure how many children live in households with income poverty, household incomes are compared to poverty lines that are set based on the overall distribution of incomes in the population. For example, a threshold for income poverty can by defined as having a disposable household income that is less than half of the median (or middle) disposable household income.

Disposable (or net) income for an individual is the total of all sources of income including tax credits, less tax payable and ACC earner’s levy. Disposable household income is the sum of the disposable incomes for all household members aged 15 years and older.

To allow for comparison between households, disposable household incomes are equivalised - adjusted for household size and composition. This reflects that larger households require more income overall than a smaller household, but there are also economies of scale for larger households. The modified Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) equivalence scale is used for equivalisation. This scale assigns a value of 1.0 to the first adult in the household, and 0.5 to each additional adult (aged 14 years or older), then 0.3 for each child aged under 14 years).12

Equivalised household disposable income is an indicator of the economic resources available to the members of the household. The household income is then compared to a threshold based on the ‘middle point’ for all households – the median equivalised disposable income. A median income is used for comparison rather than the mean, because it is less sensitive to extremes. Thresholds for income poverty are defined as less than 40%, 50% and 60% of the median equivalised disposable income.13

The income thresholds can be set using a fixed line or moving-line approach. A moving-line approach (e.g. below 50% of the (contemporary) median household income) compares a household’s income in a given year to the current median for all households in the same year. Contemporary median household incomes will change each year due to inflation and economic changes. Using this approach, a low-income household is deemed better off if it moves closer to the median, even with no change in real income. Moving-line approaches are better for assessing long-term change.13,14

The fixed line approach compares incomes to the median income in a particular base financial year: this is a constant threshold, which is adjusted for inflation. Fixed-line measures show short and medium-term change. It shows how a household income changes between years, irrespective of what happens to the incomes of other households. The fixed line measure indicates whether the real income of a household is increasing or decreasing.14

These income measures are presented before housing costs are deducted (BHC), and after housing costs are deducted (AHC), because the expense of housing (including rent, mortgage repayments, property rates and insurance) are not discretionary – all families need somewhere to live.

Child Poverty Reduction Act

In December 2018, Parliament passed the Child Poverty Reduction Act 20187 which seeks to “help achieve a significant and sustained reduction in child poverty in New Zealand” through encouraging government and society to focus on child poverty reduction, facilitating political accountability to achieve published targets, and requiring transparent reporting. The Act mandates ten primary and supplementary child poverty measures which are reported by Stats NZ.7 Data are available to monitor progress on nine of these measures. The definition for a poverty persistence measure must be decided and reported on for the financial year beginning on 1 July 2025.

Low income measures specified in the Child Poverty Reduction Act are listed below ( primary measures in bold) :

· Percentage of children living in households with less than 50 percent of the median equivalised disposable household income for the 2017/18 base financial year after housing costs are deducted

· Percentage of children living in households with less than 50 percent of the median equivalised disposable household income before housing costs are deducted (contemporary financial year)

· Percentage of children living in households with less than 60 percent of the median equivalised disposable household income without deducting housing costs (contemporary financial year)

· Percentage of children living in households with less than 60 percent of the median equivalised disposable household income after housing costs are deducted (contemporary financial year)

· Percentage of children living in households with less than 50 percent of the median equivalised disposable household income after housing costs are deducted (contemporary financial year)

· Percentage of children living in households with less than 40% of the median equivalised disposable household income after housing costs are deducted (contemporary financial year)

In 2019 the Government set three-year and ten-year targets to reduce the proportion of children living in households with equivalised income less than 50% of the contemporary median before housing costs, and less than 50% of the base financial year (2017/18) median after housing costs.15 Further three-year targets for the 2023/24 year were set in June 2021.16 All targets are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. New Zealand Government low-income targets set under the Child Poverty Reduction Act 2018.

| Primary measure |

Intermediate | Second intermediate (3‑year) target rate16 |

Long-term |

| Low-income: less than 50% of median equivalised DHI (without deducting housing costs) for financial year [Before housing costs, BHC 50% moving line] | 10.5% of children in the 2020/21 financial year | 10% of children in the 2023/24 financial year | 5% of children in the 2027/28 financial year |

| Low-income: less than 50% of median equivalised DHI (after deducting housing costs) for base financial year [after housing costs, 50% fixed line] | 18.8% of children in the 2020/21 financial year | 15% of children in the 2023/24 financial year | 10% of children in the 2027/28 financial year |

The United Nations Global Goals for Sustainable Development (SDGs) were adopted by Aotearoa and other nations in 2015. Governments must reduce the proportion of children in poverty, in all its dimensions, by at least half by 2030 (Goal 1.2).18 These goals are used in this report for the supplementary child poverty indicators

This section of the Child Poverty Monitor presents information on children living in households with low disposable incomes, using the equivalised income of the household that includes the child, as reported by the official measures of child poverty produced by Stats NZ Child Poverty Statistics19 and as reported in Child Poverty in New Zealand20 reports produced by the Ministry of Social Development.

Data sources and methods

Indicators

*Children in households below 50% of median income poverty threshold before housing costs (BHC)

Children in households below 60% of median income poverty threshold before housing costs (BHC)

Children in households below 40% of median income poverty threshold after housing costs (AHC)

Children in households below 50% of median income poverty threshold after housing costs (AHC)

Children in households below 60% of median income poverty threshold after housing costs (AHC)

* This indicator is presented by current financial year (contemporary median) and by base financial year (fixed-line)

Definitions

Children are persons aged under 18 years.

A household is one person who usually resides alone or two or more people who usually reside together and share facilities (e.g. eating, cooking, bathroom and toilet, living area).

A child is a member of a household if they live there for four or more nights per week, or spend equal time in this and another household and were present during the survey week.

Equivalised household income is the household disposable income for the previous twelve months adjusted for household size and composition.

Disposable income is calculated for each household as the: sum of taxable income, non-taxable income, working for families’ tax credits, and total rebates, less ACC earner’s levy and tax payable.

Contemporary median poverty measures are set relative to the median income for the same year. This gives a low-income threshold that rises and falls with changes in contemporary median incomes. This type of measure is also called a moving-line or relative approach. Improvement is considered to have occurred when a poor household moves closer to the median irrespective of whether income in real terms has increased or decreased.13

Base financial year poverty measures are anchored in a reference year (in this report, the reference year is 2017/18), adjusted for inflation, and kept at a constant value in real terms over other years. This type of measure is also called a constant value or anchored approach. Because it is considered most useful for examining short to medium term change, it is necessary to re-set the reference year to continue to calculate realistic rates of poverty where there have been considerable changes in New Zealand’s economy, adjusted using the consumer price index. Improvement is considered to have occurred when household income rises in real terms irrespective of what is happening to the incomes of other households .

Households are low-income where they have an income <60% of the contemporary median income

Data source

Stats NZ Child Poverty Statistics

New Zealand Household Economic Survey (NZHES) via Perry (2022).20

Additional information

The median is a more stable measure of household incomes than the mean. A few households with a very high income will shift the mean upwards, and the number of very-high-income households varies from year to year.

All dates are for year ended June 30. Data collection finished in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, so the sample size is smaller for the 2019/20 survey than for other years.

The 2009 financial year is the first year for which data are available using the 2017/18 base financial year (fixed-line measure). Data for the contemporary median measures are available from 2007 (Table 2 ).

Table 2. Children in low-income households, by selected poverty thresholds, Aotearoa 2006/07–2020/21

| Year | Before housing costs (BHC) | After housing costs (AHC) | ||||||||||

| Children in low-income households | ||||||||||||

| <50% contemporary median | <60% contemporary median | <40% contemporary median | <50% contemporary median | <60% contemporary median | <50% fixed-line median* | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 2006/07 | 150,800 | 14.0 | 256,800 | 23.9 | 163,900 | 15.3 | 240,500 | 22.4 | 314,200 | 29.3 |

|

|

| 2007/08 | 155,900 | 14.5 | 251,800 | 23.4 | 155,900 | 14.5 | 257,800 | 23.9 | 355,200 | 33.0 |

|

|

| 2008/09 | 150,600 | 14.0 | 239,500 | 22.2 | 165,200 | 15.3 | 256,300 | 23.8 | 338,700 | 31.4 | 328,600 | 30.5 |

| 2009/10 | 152,500 | 14.1 | 242,400 | 22.4 | 160,400 | 14.8 | 237,400 | 21.9 | 321,900 | 29.7 | 291,100 | 26.9 |

| 2010/11 | 161,900 | 14.9 | 253,400 | 23.3 | 175,500 | 16.1 | 238,000 | 21.9 | 328,100 | 30.2 | 335,300 | 30.9 |

| 2011/12 | 160,900 | 14.8 | 252,800 | 23.3 | 176,800 | 16.3 | 240,700 | 22.2 | 314,300 | 28.9 | 315,600 | 29.1 |

| 2012/13 | 169,000 | 15.6 | 255,500 | 23.6 | 169,000 | 15.6 | 237,600 | 21.9 | 318,300 | 29.3 | 292,300 | 26.9 |

| 2013/14 | 157,500 | 14.5 | 253,900 | 23.4 | 171,700 | 15.8 | 248,800 | 23.0 | 317,800 | 29.3 | 295,900 | 27.3 |

| 2014/15 | 177,200 | 16.3 | 267,900 | 24.6 | 168,200 | 15.5 | 258,500 | 23.8 | 331,200 | 30.5 | 295,600 | 27.2 |

| 2015/16 | 168,300 | 15.4 | 254,400 | 23.3 | 177,600 | 16.2 | 244,200 | 22.3 | 325,700 | 29.8 | 265,400 | 24.3 |

| 2016/17 | 156,300 | 14.2 | 243,300 | 22.1 | 178,000 | 16.1 | 235,600 | 21.4 | 313,600 | 28.4 | 247,500 | 22.4 |

| 2017/18 | 183,400 | 16.5 | 281,200 | 25.3 | 174,300 | 15.7 | 253,800 | 22.8 | 341,100 | 30.6 | 253,800 | 22.8 |

| 2018/19 | 153,200 | 13.5 | 250,300 | 22.1 | 156,100 | 13.8 | 227,900 | 20.1 | 313,200 | 27.7 | 207,700 | 18.3 |

| 2019/20 | 151,200 | 13.2 | 248,900 | 21.8 | 151,400 | 13.2 | 222,800 | 19.5 | 318,100 | 27.8 | 203,300 | 17.8 |

| 2020/21 | 156,700 | 13.6 | 249,000 | 21.7 | 150,400 | 13.1 | 236,900 | 20.6 | 322,900 | 28.1 | 187,300 | 16.3 |

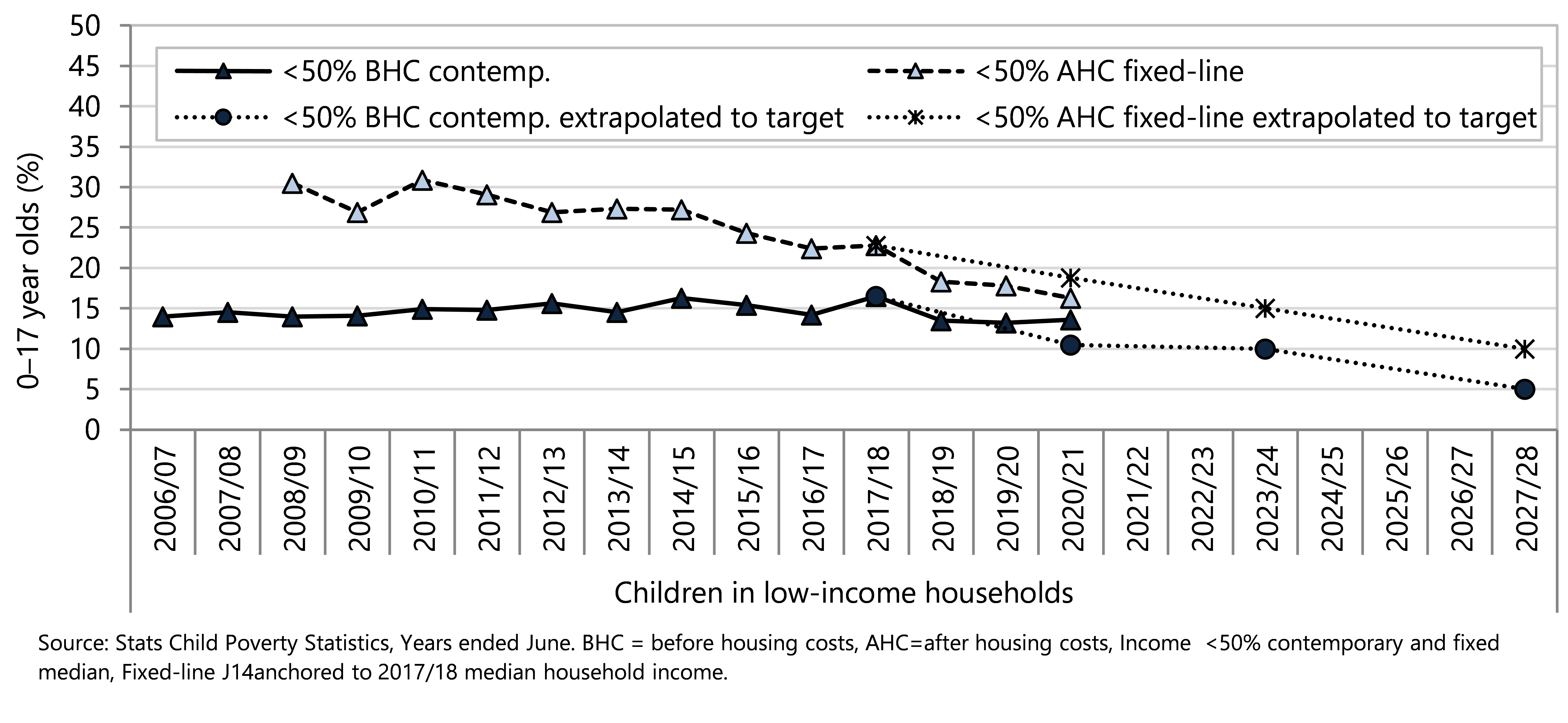

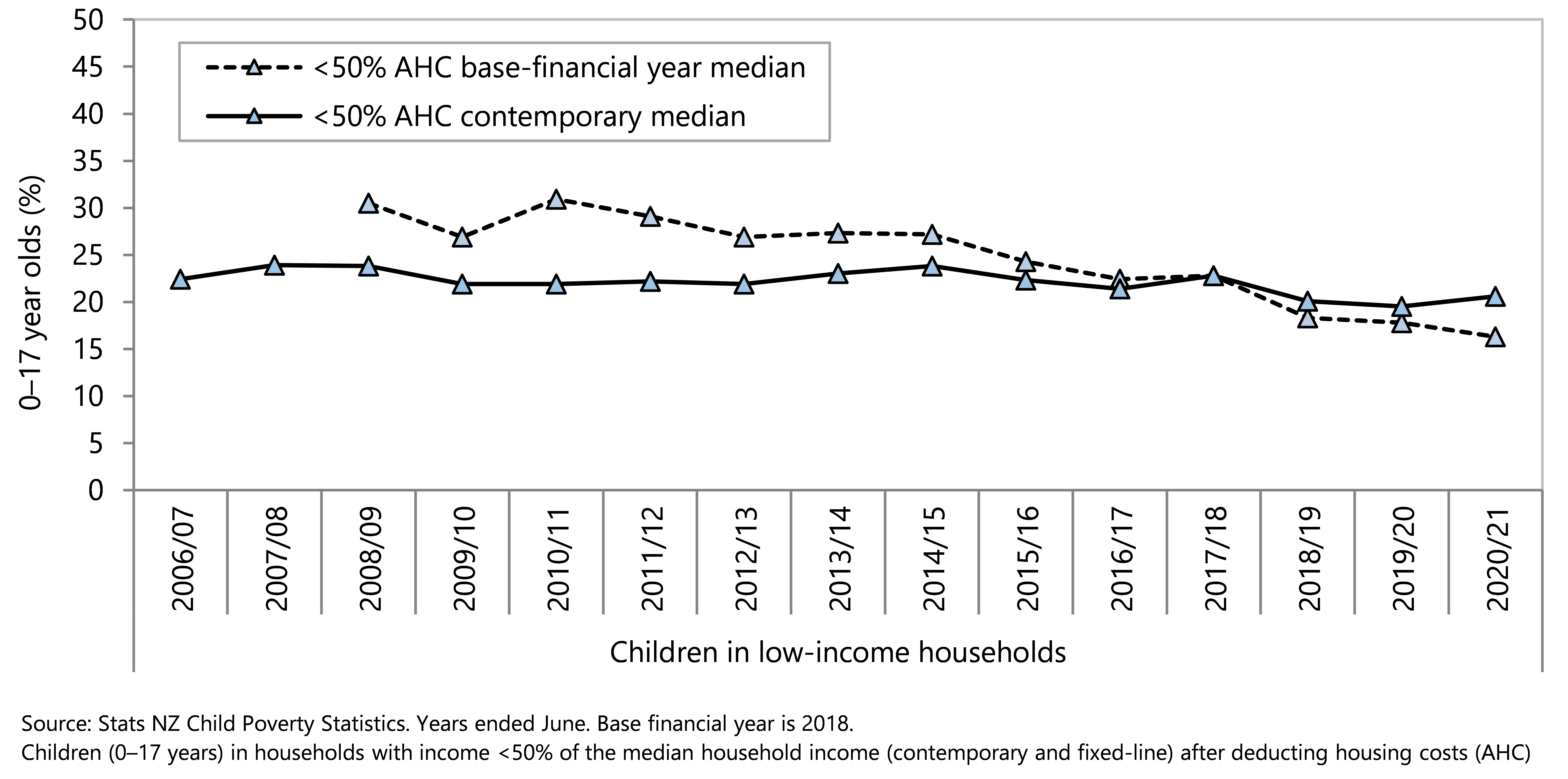

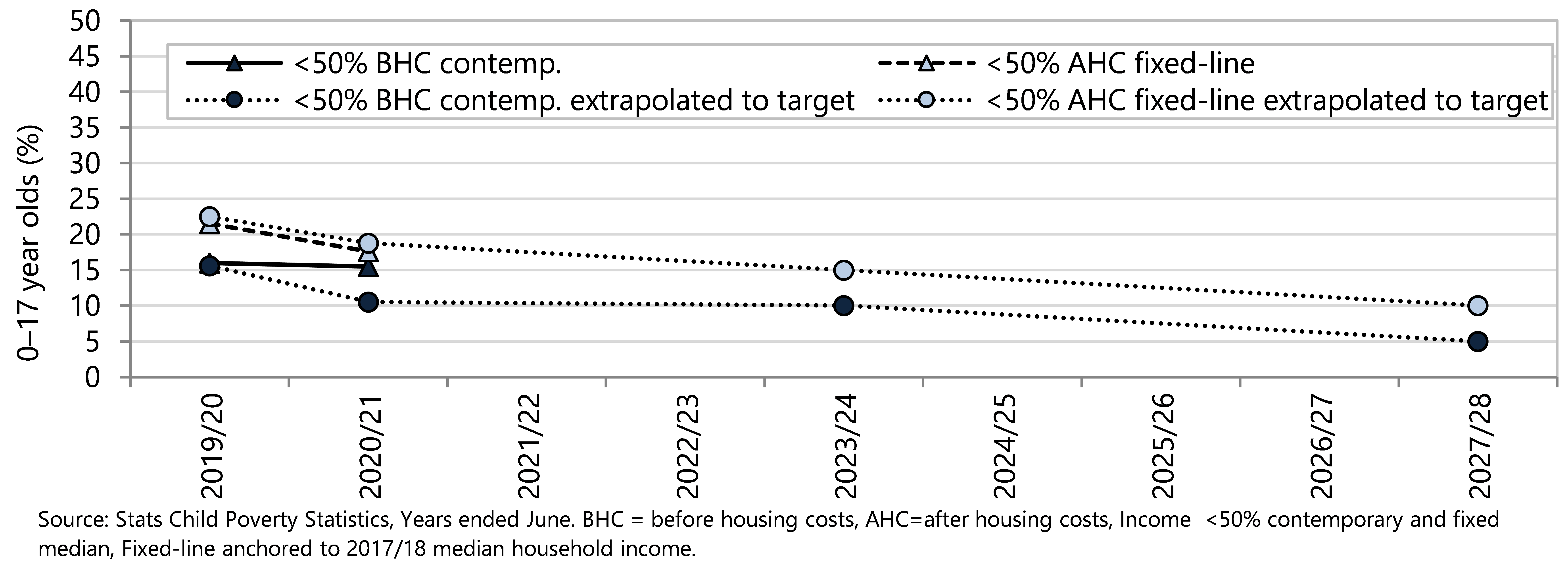

There has been an overall decline in the proportion of children living in households with equivalised disposable income less than 50% of the fixed-line median income after housing costs since 2008/09. The rate of decline in this measure will need to continue in order to achieve the 2023/24 Government target of 15.0% (Figure 1). In 2020/21 there were an estimated 187,300 children (16 children in every 100) living in households with equivalised disposable income below 50% of the 2017/18 base financial year after housing costs.

The proportion of children living in households with equivalised disposable income less than 50% of the contemporary (moving-line) median income before housing costs rate has shown year-to-year fluctuation but has not substantially changed since 2006/07, and at 13.6% is well above the 2020/21 target of 10.5%. There will need to be a significant decline in this proportion to meet the 2023/24 Government target of 10%.

Figure 1. Children in low-income households (less than 50% contemporary median income before housing costs and less than 50% fixed-line median income after housing costs), Aotearoa, 2006/07–2020/21 with extrapolations to Government targets

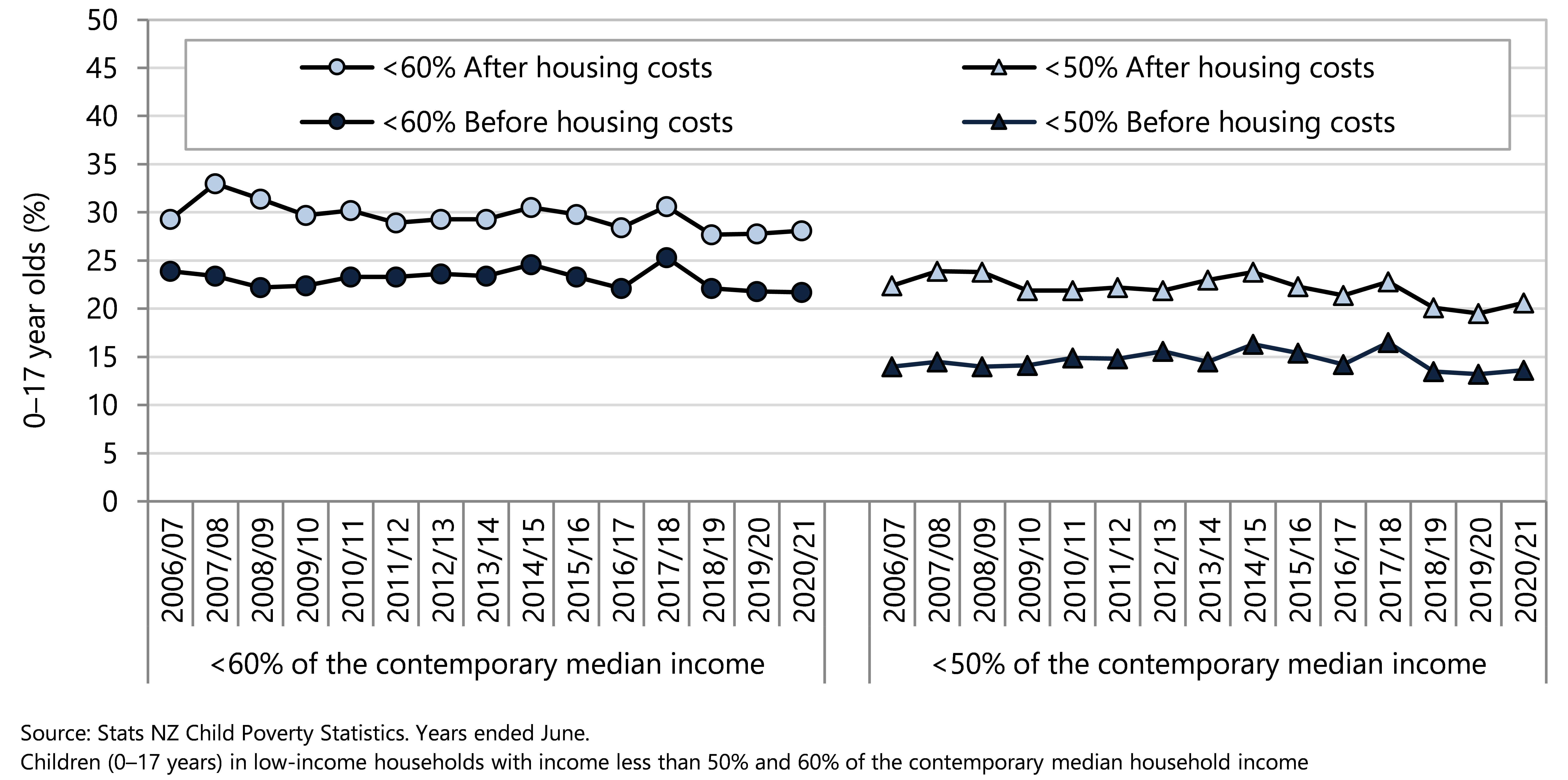

Figure 2 shows the impact of housing costs on the proportion of children living in households with equivalised disposable income less than 50% and less than 60% of the contemporary (moving-line) median income. The effect of housing costs on the proportion of children living in income-poor households has been consistent since around 2012 (Table 2, Figure 2). Before housing costs were deducted, an estimated 249,000 children (21.7%, more than one in five children) lived in households with an equivalised disposable income less than 60% of the contemporary median household income in 2020/21 (Table 2, Figure 2). The impact of housing costs meant that an additional 73,900 children lived in a low-income household (less than 60% of the contemporary median) after housing costs were deducted (Table 2, Figure 2). This is equivalent to an additional 6.4% of children living in households experiencing income poverty (less than 60% contemporary median) due to the impact of housing costs on disposable household income.

A similar pattern is seen for children living in households with equivalised disposable income less than 50% of the contemporary median income. Using this measure, an additional 80,200 children lived in a household with an income less than 50% of the contemporary median after housing costs were deducted (Table 2, Figure 2). Accounting for housing costs increased the proportion of children living in low-income households (less than 50% contemporary median) from 13.6% to 20.6%.

Figure 2. Children in low-income households (less than 50% and less than 60% of the contemporary median income) before and after housing costs, Aotearoa 2006/07-2020/21

Figure 3 compares base financial year (fixed line) low-income measures with financial year (contemporary median) measures for the proportion of children in low-income households using a less than 50% of the median equivalised disposable income threshold. The base financial year for the fixed-line measure is 2017/18.

Without consideration of the income changes experienced by other households, disposable incomes in some low-income households with children have increased in real dollar terms between 2010/11 to 2020/21 with a decline of the proportion of children in low-income households (Table 2, Figure 3).

When taking into account income changes experienced by all households, the disposable incomes in low-income households have remained relatively stable compared to the (contemporary) median household income for each year, with 20.6% of 0–17 year olds living in low-income households (Table 2, Figure 3).

Figure 3. Children in low-income households (income less than 50% of the contemporary and fixed-line median household income) after housing costs (AHC), Aotearoa 2006/07-2020/21

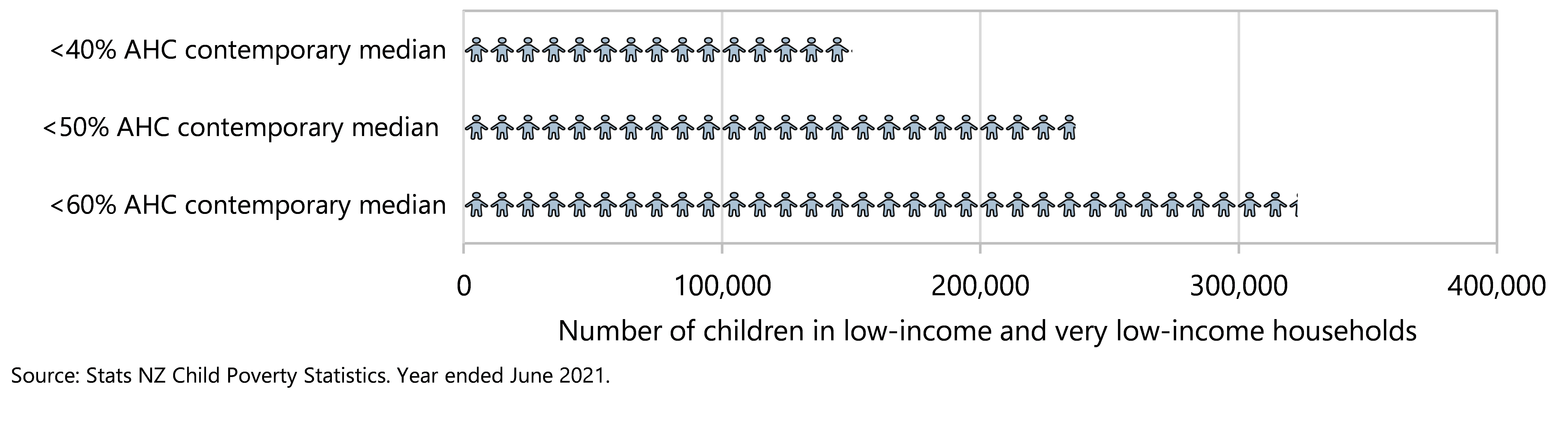

For every 100 children in 2020/21, an estimated 13 children lived in a household with an equivalised disposable income less than 40% of the median household income for that year, after housing costs; 21 children lived in a household with income less than 50% of the median, and 28 children lived in a household with income less than 60% of the median (Table 2). In numerical terms, after taking housing costs into consideration, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 4, there were approximately:

· 150,400 children (13.1%) living in a very-low-income household (equivalised disposable income less than 40% of the contemporary median)

· 236,900 children (20.6%) living in a low-income household (equivalised disposable income less than 50% of the contemporary median)

· 322,900 children (28.1%) living in a household with equivalised disposable income less than 60% of the contemporary median.

Figure 4. Children in low-income and very low-income households (income less than 40%, 50% and 60% of the median household income) after housing costs (AHC), by income threshold, Aotearoa 2020/21

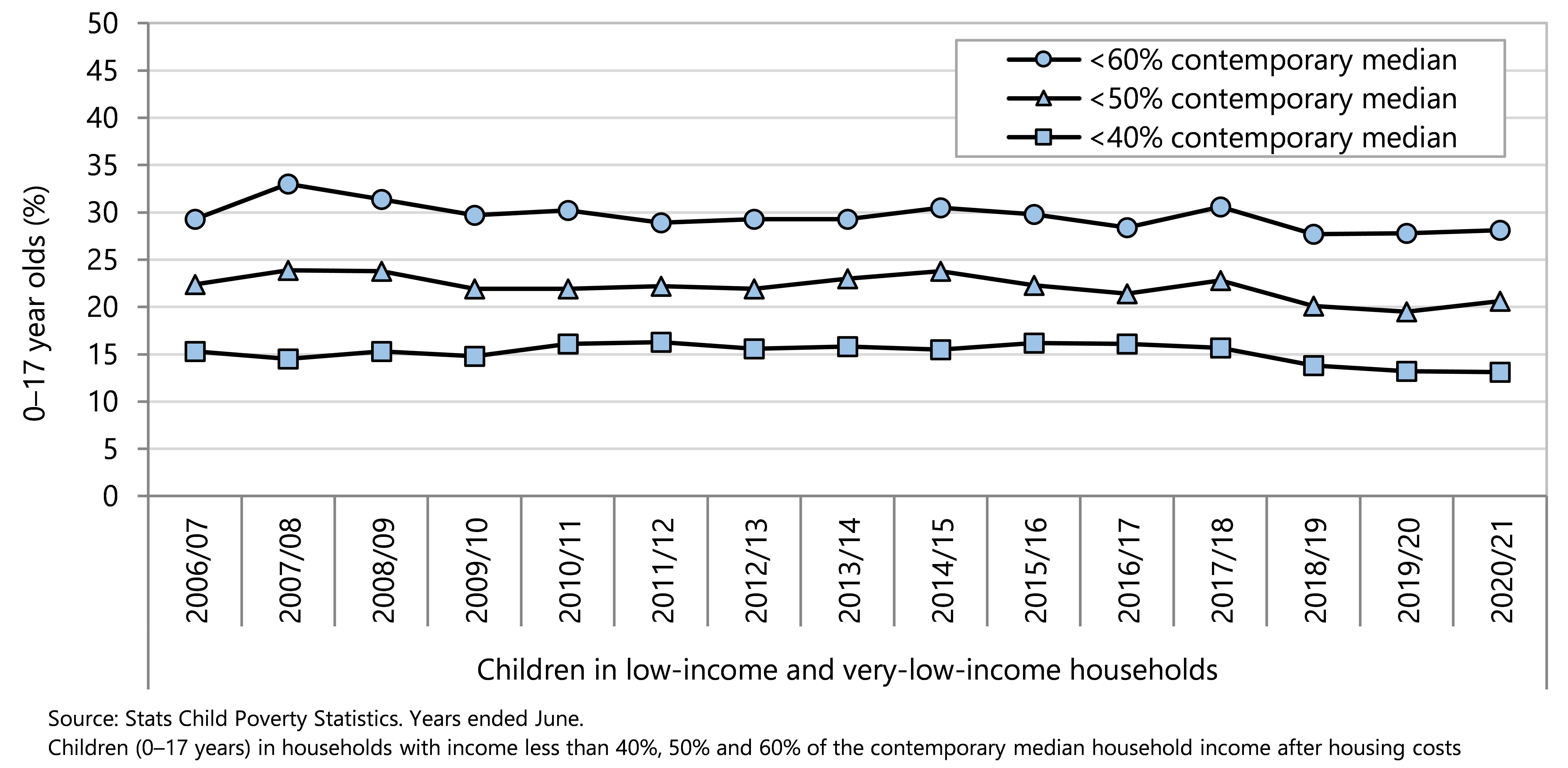

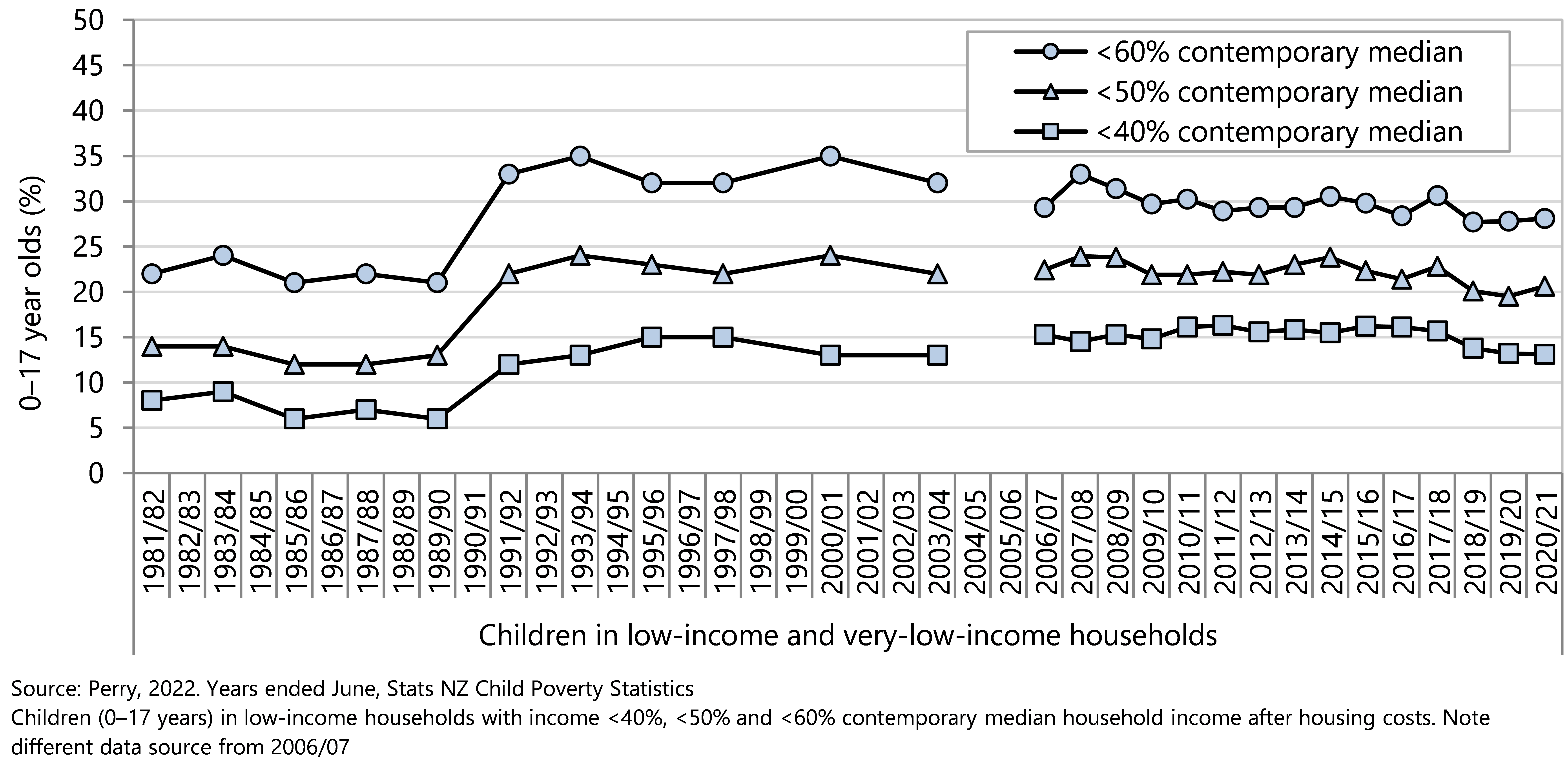

Since 2006/07, over 300,000 children have lived in a household with an equivalised disposable income less than 60% of the median after housing costs for that year, and in 2020/21, almost one in seven lived in households experiencing severe income poverty (less than 40% of the median income) ( Table 2, Figure 5). Since 2010/11, there has been a slight decline in the proportion of children living in low‑income households using the contemporary median measures (Figure 5). Data collection for the 2019/20 year stopped in March 2020 and was interrupted in 2020/21 due to COVID-19 pandemic protections, and so the sample sizes were smaller than planned in those survey years.21 Despite the reduction in sample size with higher margins of error, Stats NZ is confident the data are fit for purpose.

Figure 5. Children in low-income and very low-income households (less than 40%, 50% and 60% contemporary median after housing costs), Aotearoa 2006/07–2020/21

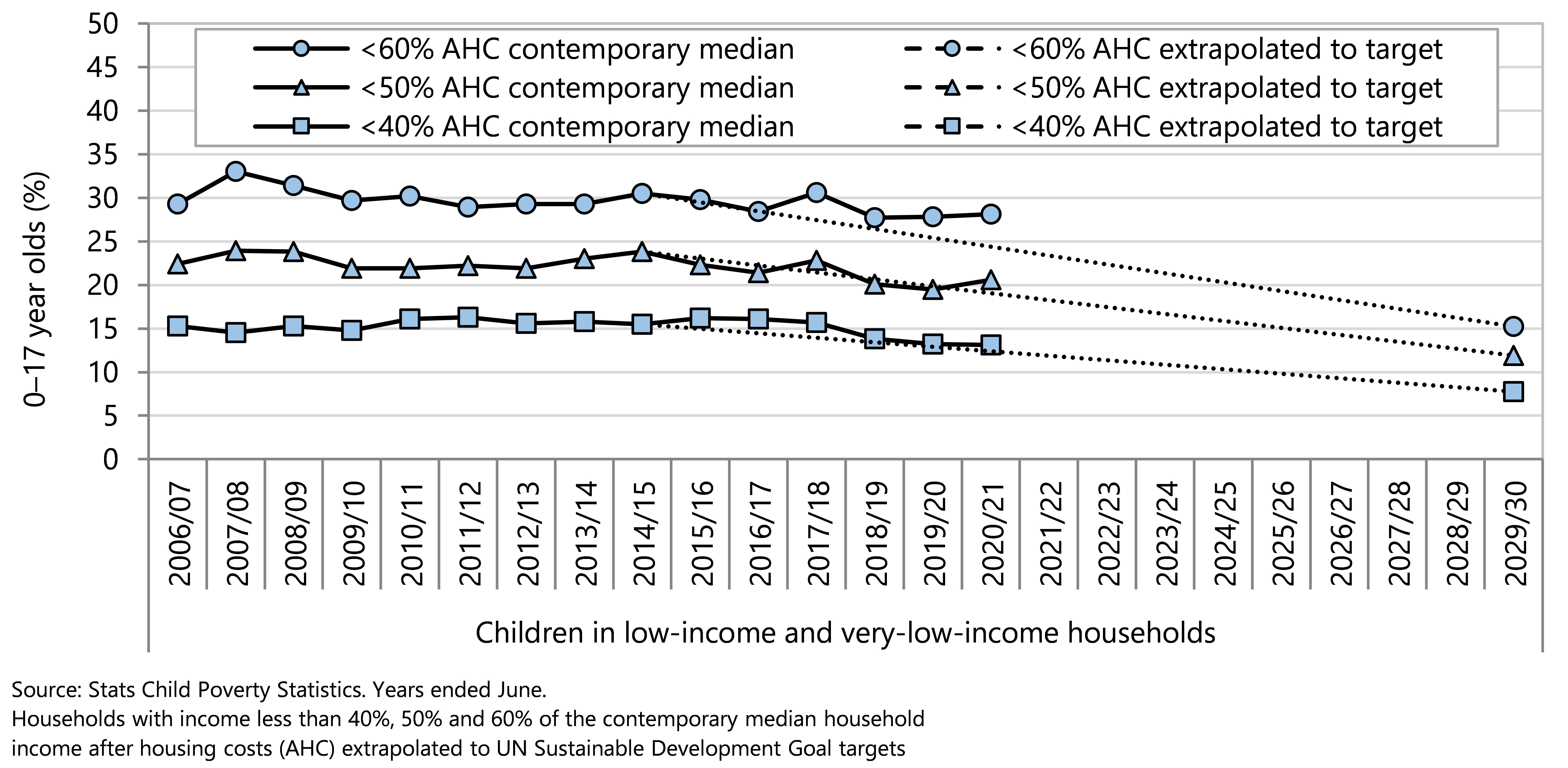

The United Nations (UN) global goals for sustainable development (SDGs) include reducing all forms of poverty to at least half of the values as at 2015.18 Figure 6 applies the SDG targets to contemporary median thresholds for child poverty, after housing costs, which are supplementary measures set out in the Child Poverty Reduction Act 2018.7

Government will need to implement effective policies to reduce the proportion of children living in low-income and very-low-income households in order to achieve the 2030 SDG targets for child poverty reduction (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Children in low-income and very low-income households (less than 40%, 50% and 60% contemporary median after housing costs) extrapolated to UN Sustainable Development Goal targets, Aotearoa 2006/07–2029/30

A longer-term perspective

A long-run time series from the Ministry of Social Development13,20 (using older methodology for calculating income poverty) shows the proportion of children living in low- and very-low-income households. In the 1980s, 18-20% of households with children experienced income poverty after housing costs, when compared to the fixed median incomes. This proportion sharply increased in the early 1990s; at this time there was high unemployment, decreased average wages, benefit cuts, and introduction of market rents for social housing.13 Since this time, there have been changes in taxation/tax credits (Working for Families), higher employment (especially for women), increased average wages, and income-related rents for social housing, which has decreased the proportions of households with income poverty from the 1990s.13

Since 2013, the proportion of households with children in low-income households, after housing, (compared to fixed median incomes) has declined, reflecting good economic conditions, a rising minimum wage and, more recently, higher housing support through changes to the Accommodation Supplement and increases in incomes for beneficiary families and households.

The proportion of children who have income poverty after housing costs, (relative to the contemporary median) remained fairly stable from 1993 to 2018, with a slight decline since then; this suggests that there has not been a marked change in income inequality (after housing costs) at the lower end of the income distribution (Figute 7).

Figure 7 . Children in low-income and very low-income households (income less than 40%, 50% and 60% of the contemporary median household income) after housing costs (AHC), Aotearoa 1981/82–2021

Essentials for a good life

Day-to-day living conditions in which children live, learn, grow, and play affect their health and wellbeing.22,18 Access to essential items is associated with equitable opportunities for children and young people to thrive and reach their potential.22 Material hardship at household level in Aotearoa is monitored using a 17-item index (DEP-17) that determines whether households experience enforced lack of essentials due to cost, a high level of economising in order to afford essentials, insufficient funds to pay for essential services, or high levels of financial stress and vulnerability. All 17 items in the DEP-17 index are considered essential and are enjoyed by almost all households. An enforced lack is where a household misses out on an item in the DEP-17 index because of cost.23 Material hardship is defined where a household experiences the enforced lack of six or more essentials. Severe material hardship is when a household experiences the enforced lack of nine or more essentials on DEP-17.24 Material hardship reflects the day-to-day living conditions of the households in which children live.

The New Zealand Government has set intermediate and long-term targets for reduction of material hardship, as shown in Table 3 .

Internationally, the Sustainable Development Goals require that material hardship, or unacceptably low material wellbeing,13 be reduced by at least half between 2015 and 2030 (Goal 1.2) as a dimension of poverty.

This section of the Child Poverty Monitor presents information on children aged 0–17 years living in households experiencing material hardship using data gathered in the New Zealand Household Economic Surveys (NZHES) and analysed using DEP-17. The most recent data are from the 2021 NZHES year (ending June 2021).

Table 3. New Zealand Government material hardship target set under the Child Poverty Reduction Act 2018.

| Primary measure | Intermediate (3-year) target | Second intermediate (3-year target) | Long-term (10-year) target |

| Material hardship | 10.3% of children in the 2020/21 financial year | 9% of children in the 2023/24 financial year | 6% of children in the 2027/28 financial year |

| Source: New Zealand Gazette 16,17

| |||

Data sources and methods

Indicator

Children in households experiencing material hardship

Children in households experiencing severe material hardship

Definitions

Children are persons aged under 18 years.

A household is one person who usually resides alone or two or more people who usually reside together and share facilities (e.g. eating, cooking, bathroom and toilet, living area).

A child is a member of a household if they live there for four or more nights per week, or spend equal time in this and another household and were present during the survey week.

Material hardship is unacceptably low material wellbeing.13 Experienced by children, material hardship is living in households who were lacking basic/essential child-specific items because of cost. Where a household does not have the opportunity to have or do an essential because of cost, it is considered an enforced lack .

The material hardship threshold is an enforced lack of six or more (≥6) DEP-17 items.23

The severe material hardship threshold is an enforced lack of nine or more (≥9) DEP-17 items.23

Data sources

Stats NZ Child Poverty Statistics 19, Perry report: Child Poverty in New Zealand.20

Additional information

DEP-17 is an index of material hardship or deprivation, particularly suited to capturing the living standards of those at the low end of the material living standards continuum.25

DEP-17 items

Enforced lack of essentials (because of cost)

Do not have a meal with meat, fish or chicken (or vegetarian equivalent) at least each 2nd day

Do not have two pairs of shoes in good repair and suitable for everyday use

Do not have suitable clothes for important or special occasions

Do not give presents for family and friends on special occasions

Do not have home contents insurance

Economised, cut back or delayed purchases ‘a lot’ because money was needed for other essentials

Went without fresh fruit and vegetables

Bought cheaper cuts of meat or bought less than would have liked

Postponed visits to the doctor

Postponed visits to the dentist

Did without or cut back on trips to the shops or other local places

Put up with being cold (to keep costs down)

Delayed repairing or replacing broken or damaged appliances

Restrictions

Feel ‘very limited’ by money available when thinking about purchasing clothes or shoes for self

Could not pay an unexpected and unavoidable bill of $500 within a month without borrowing

Financial stress and vulnerability

In arrears more than once in last 12 months, because of shortage of cash at the time, not through forgetting:

Rates, electricity, water

Vehicle registration, insurance or warrant of fitness

Borrowed from friends or family more than once in last 12 months to cover everyday living expenses

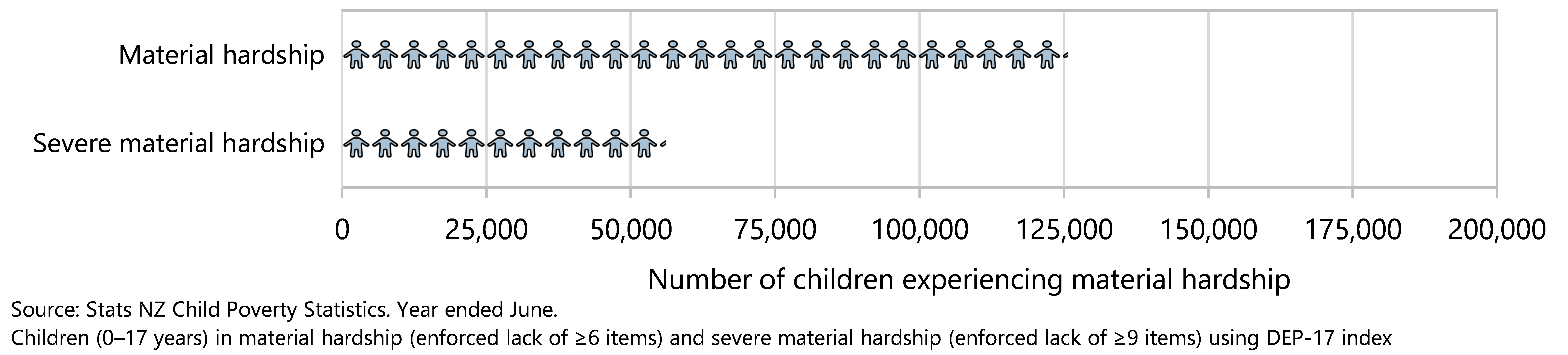

In 2020/21 almost 126,000 children in Aotearoa were in households that experienced unacceptably low material wellbeing, having to go without six or more of the essentials in DEP-17 (Figure 8). This represented 11.0% of all children. Essential lacks (due to cost) included in the DEP-17 index include postponing a visit to the doctor, putting up with feeling cold, not having two pairs of good shoes, going without fresh fruit or vegetables, or inability to pay the electricity or gas bills on time.

In the same year, 4.9% of children (approximately 56,100) experienced severe material hardship, having to go without nine or more essentials due to cost (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Children in households experiencing material hardship, by hardship threshold, Aotearoa 2020/21

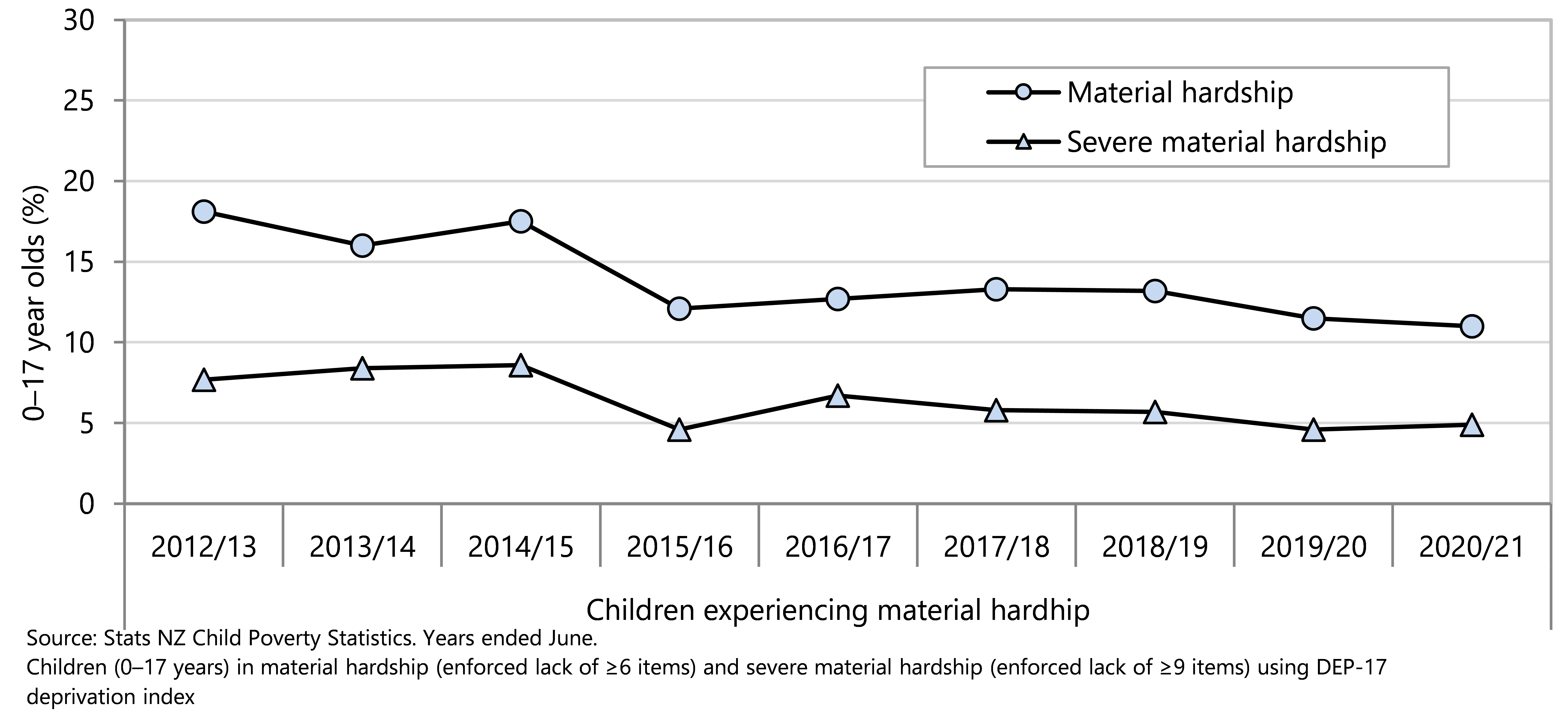

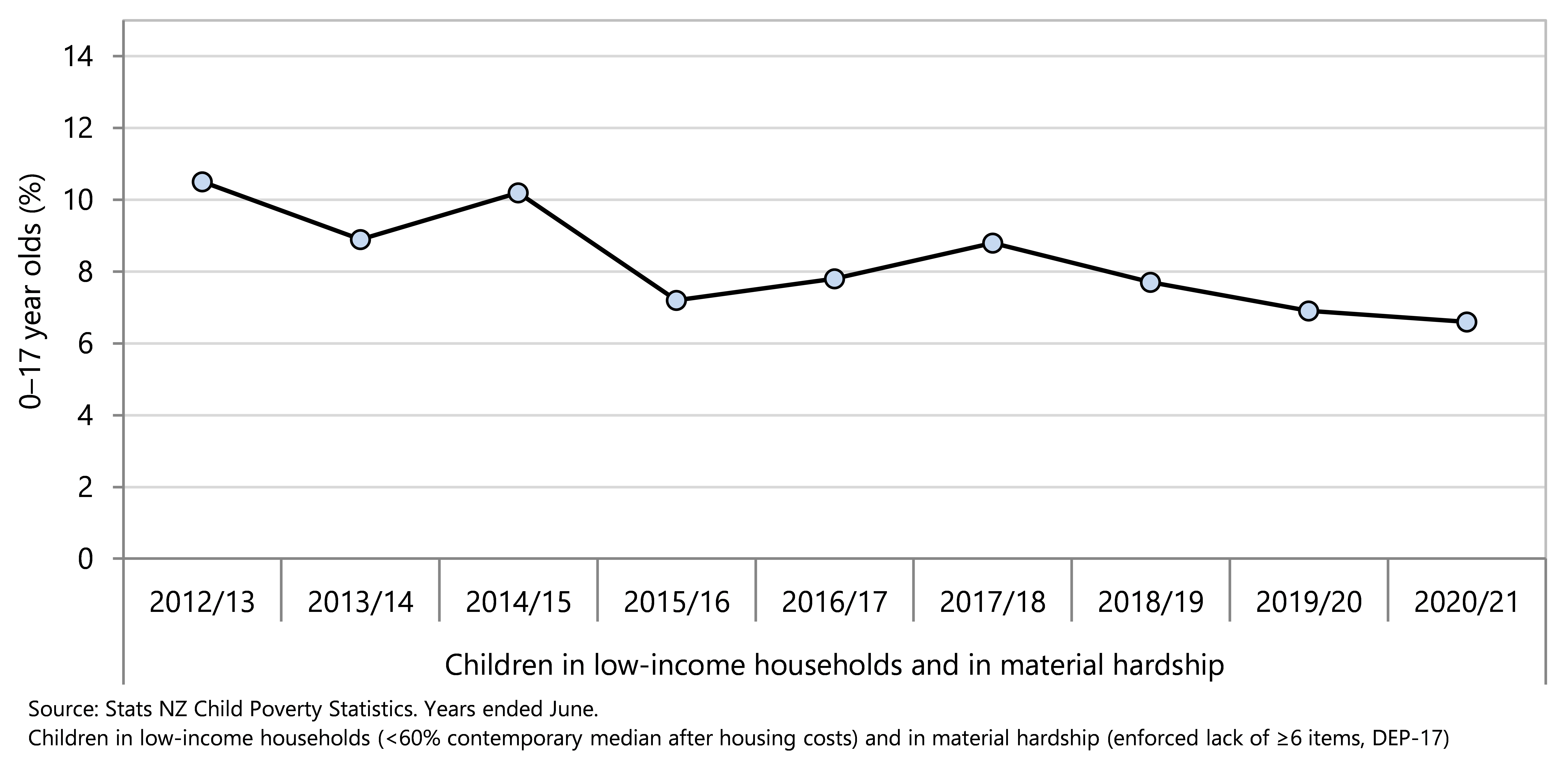

Since 2012/13, there has been an overall decline in the percentage of children in households experiencing material hardship and severe material hardship. Over this time-frame, an estimated 70,100 fewer children are living in households missing out on six or more essentials in 2020/21 compared with 2012/13 (Figure 9). The lower rate of material hardship in 2015/16 needs to be interpreted with caution, noting that in the household economic survey ending June 2016 there were fewer than expected sole parent households and households with children receiving financial assistance.24

Figure 9. Children in households experiencing material hardship, by hardship threshold, Aotearoa 2012/13-2020/21

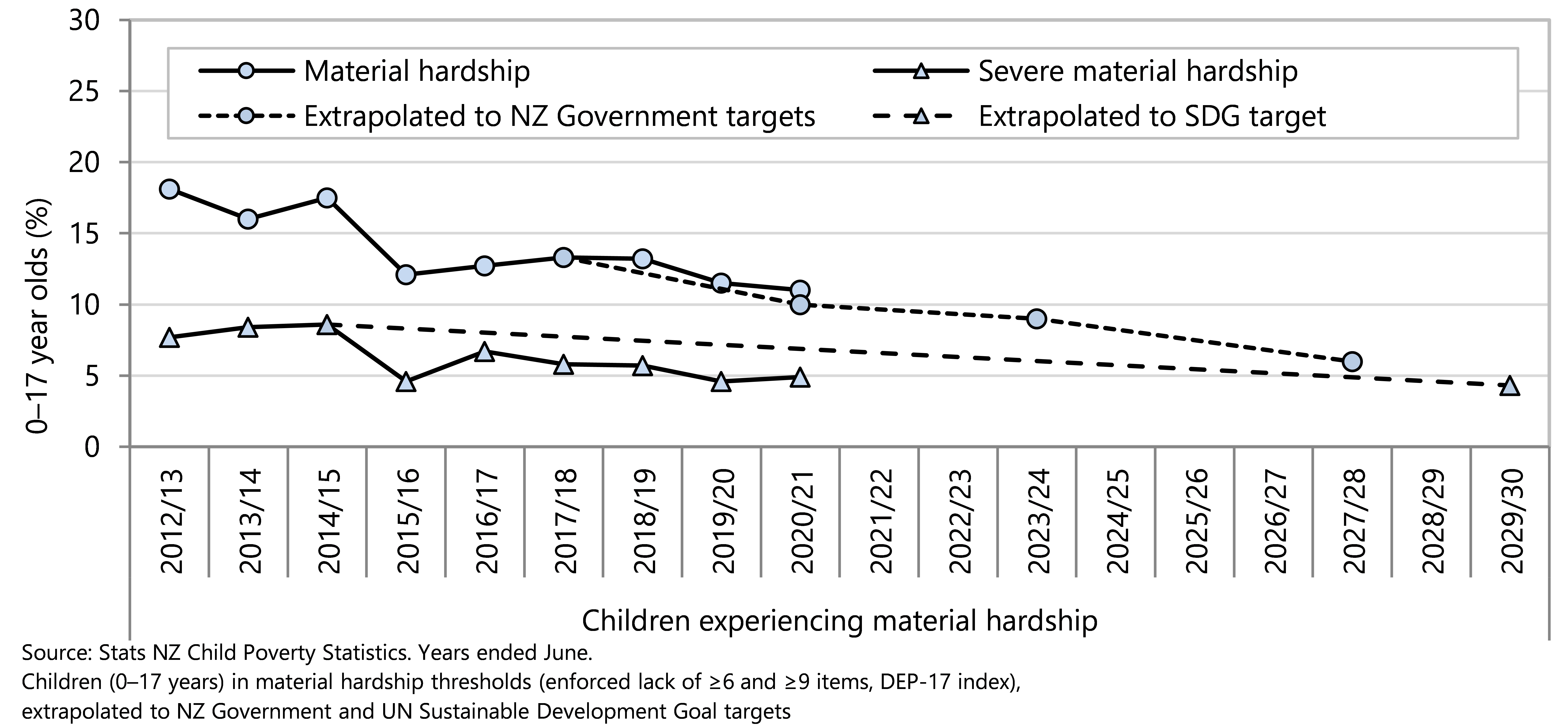

In 2020/21 the percentage of children in material hardship was 0.7% above the target and 5.0% from the 2027/28 target (Figure 10). In the case of severe material hardship, where there is no government target, Figure 10 shows that the percentage of children living in households with enforced lack of nine or more essentials in DEP-17 in 2020/21 was lower in 2019/20 and 2020/21 than in most previous years.

Figure 10 . Children in households experiencing material hardship, by hardship threshold, extrapolated to NZ Government and UN Sustainable Development Goal targets, Aotearoa, 2012/13–2030

Combined measures of income and access to essentials

Children in households that experience low income and material hardship have the greater restrictions on day-to-day activities than either households that are income-poor but not in material hardship, or households that experience material hardship but do not meet a low-income threshold.20 Not all households with low income experience material hardship; protective factors include the availability of liquid financial assets (savings and accessible investments), low levels of debt, whanau and community support, the ability to grow food, and access to less expensive housing such as papakāinga. Conversely it is possible to experience hardship while having a household income above the threshold, if there are significant costs for housing, health, or debt servicing.

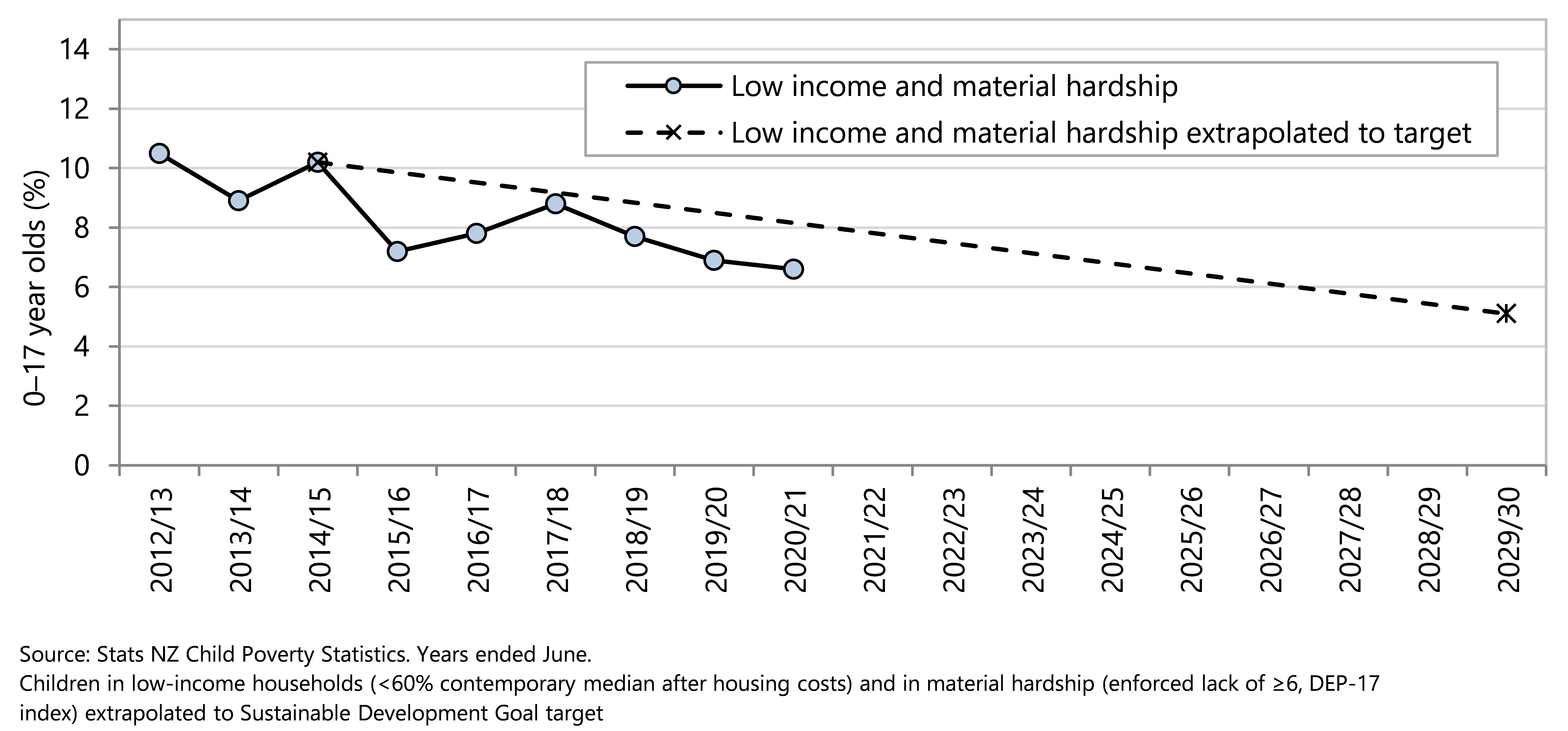

In 2020/21 there were an estimated 76,100 children (6.6%) living in households with equivalised incomes less than 60% of the contemporary median household income after housing costs who also experienced an enforced lack of six or more of essentials in the DEP-17 index. There was an overall decline in the percentage of children in households experiencing both material hardship and income poverty from 2012/13 to 2020/21, with an estimated 37,700 fewer children in these circumstances in 2020/21 compared with 2012/13 (Figure 11). This overall decline will need to be sustained in order to at least meet the UN Sustainable Development Goal target of halving this measure of poverty for children in Aotearoa by 2030 (Figure 12).

The combined measure specified in the Child Poverty Reduction Act is:

· Percentage of children living in households with less than 60% of the median equivalised disposable household income after housing costs are deducted and experiencing material hardship

Figure 11. Children in households with both low income and material hardship, Aotearoa 2012/13–2020/21

Figure 12. Children in households with both low income and material hardship extrapolated to UN Sustainable Development Goal target, Aotearoa 2012/13–2029/30

Leave no child behind

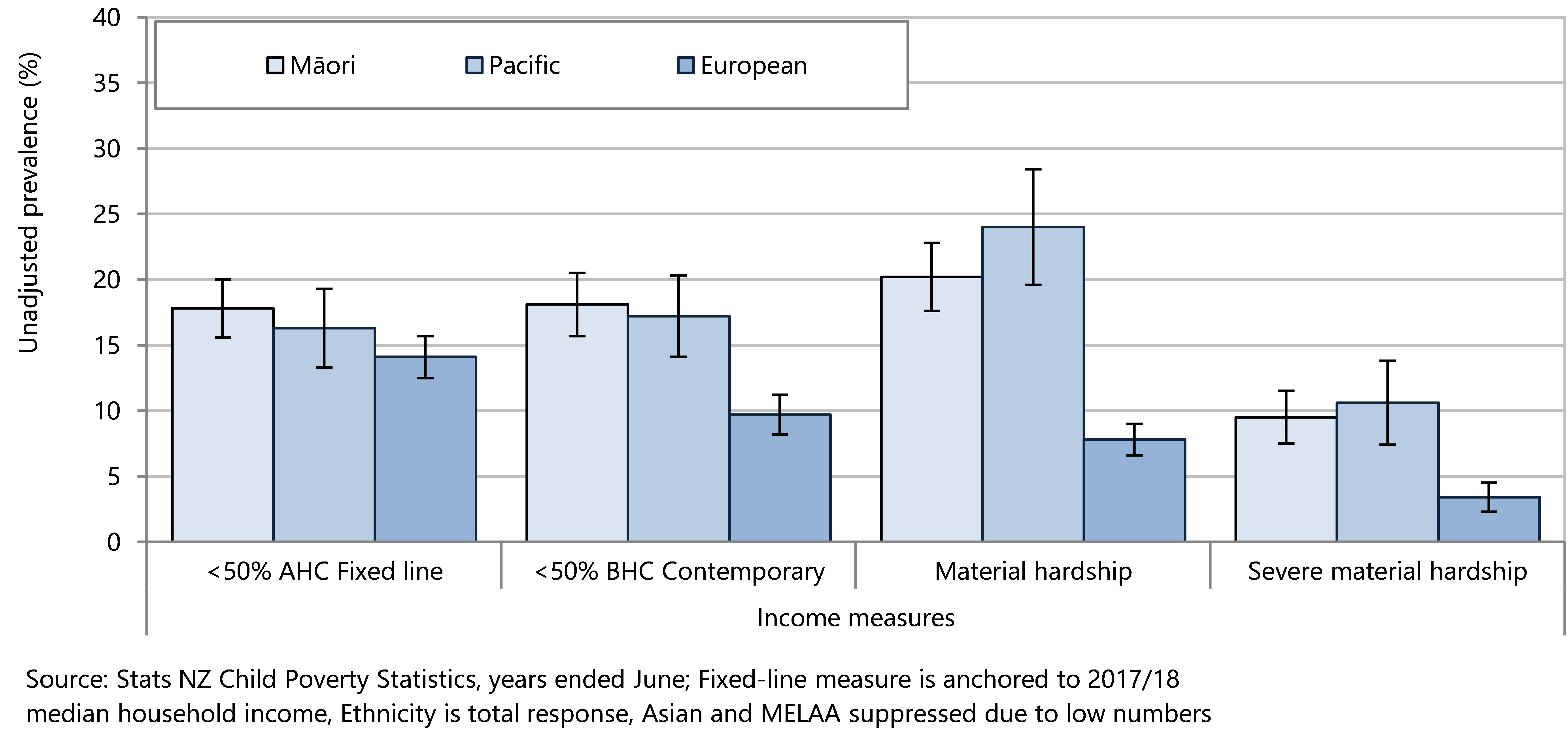

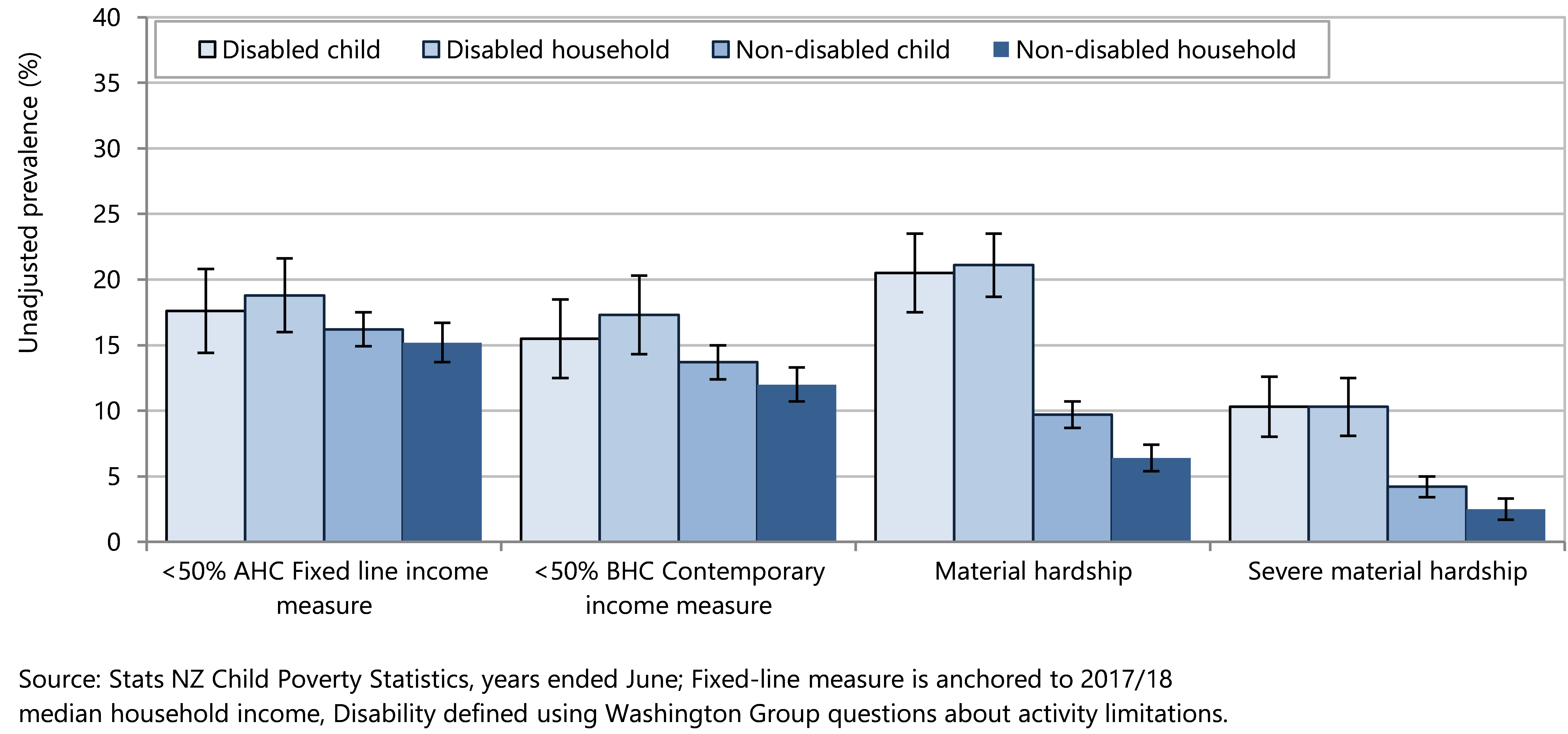

In looking at overall progress toward the Government targets it is possible to overlook inequity in outcomes between groups of children. The 2020/21 Child Poverty Statistics presented data for disabled children, non-disabled children, children living in households with at least one disabled person and children living in households with no disabled people. Data by ethnicity are available in the Child Poverty Statistics from 2018/19 to 2020/21. 19

This indicator presents information from the Child Poverty Statistics dataset on progress toward Government targets for the three current primary measures of child poverty. Stats NZ uses total response ethnicity data, in which children who identify with more than one ethnic group will be counted in both groups. Percentages may therefore add to more than 100%.

As seen earlier in this section, in 2020/21 overall 13.6% of under-18-year-olds were living in households with equivalised disposable income before housing costs below 50% of the contemporary median, and 16.3% were living in households with equivalised disposable income after housing costs below 50% of the fixed-line median (anchored to the 2017/18 financial year). These figures were on track to meet, or had already met, the Government’s 2020/21 targets.

When disaggregated by ethnicity it is evident that the combination of historical and recent policies has advantaged European children (Figure 13). Interventions to date have left Māori and Pacific children behind with 18.1% of Māori children living in households with equivalised disposable income before housing costs below 50% of the contemporary median (2020/21 target is 10.5%) and 17.2% of Pacific children in this category. The 2020/21 Government target is for 18.8% of children to be living in households with equivalised disposable income after housing costs below 50% of the fixed-line median; in 2020/21 this figure was 17.8% for Māori children and 16.3% for Pacific children.

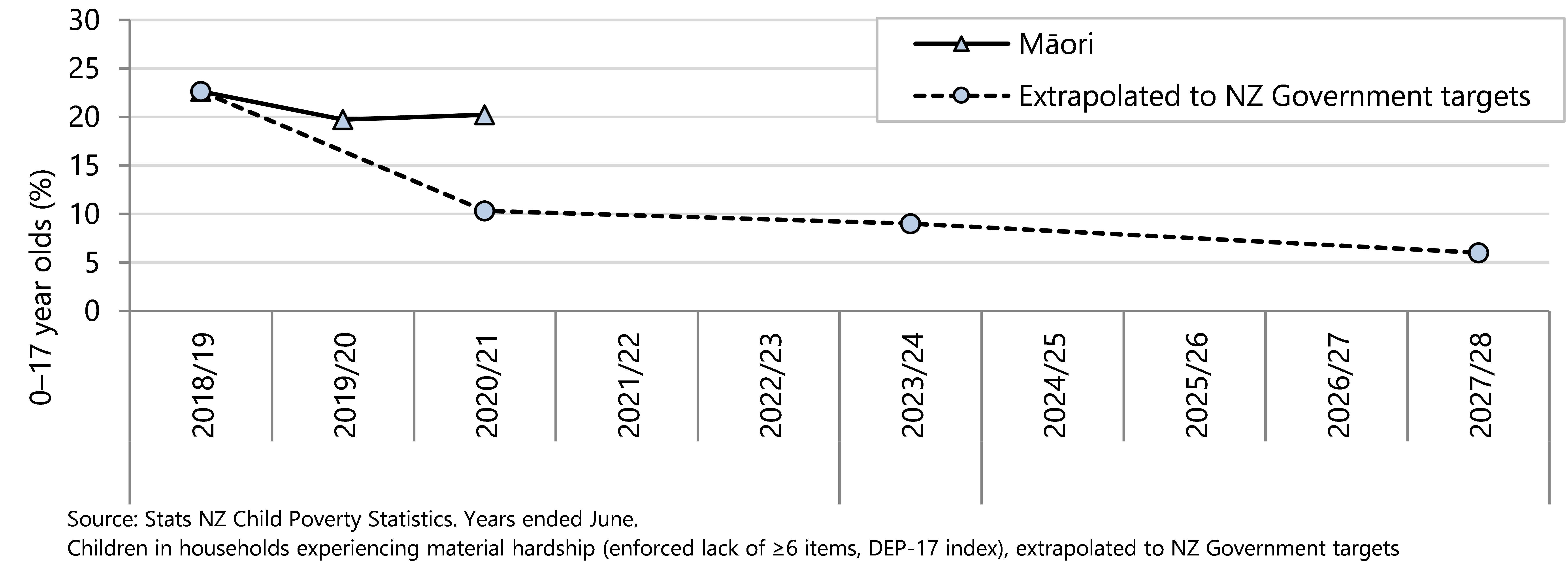

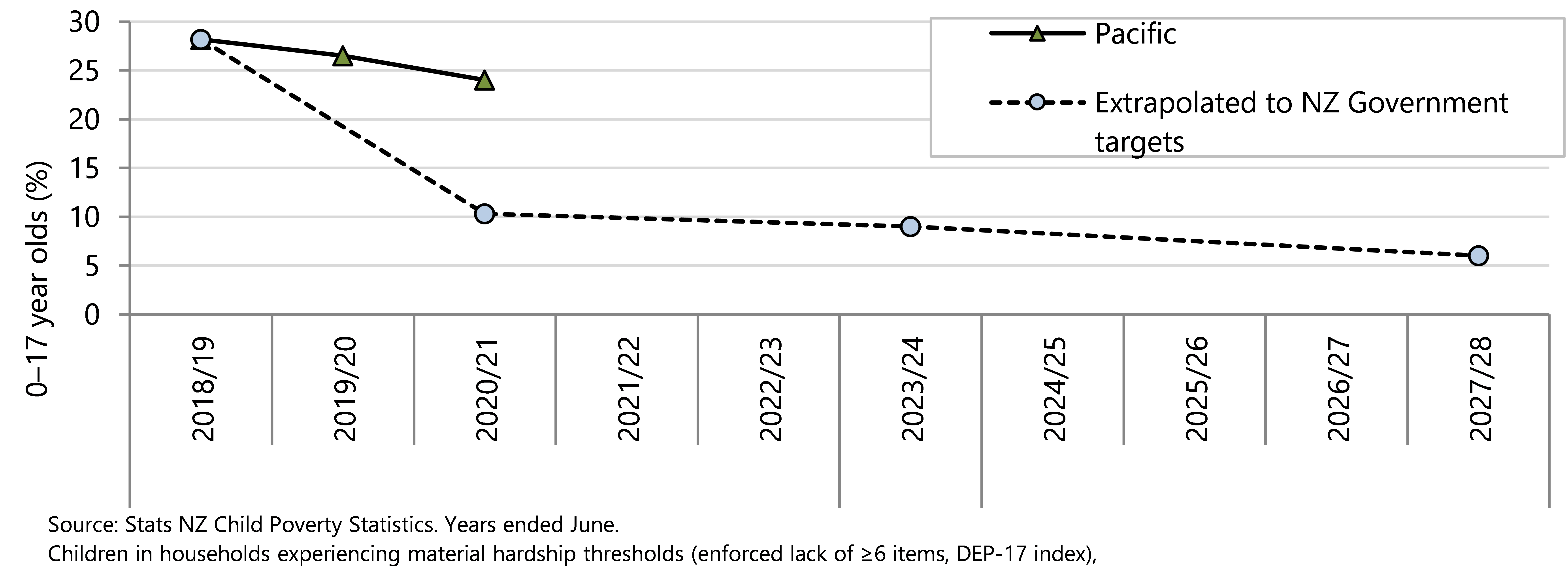

The difference was even greater for material hardship, with European 0–17 year olds already well below the target of 10.3% of children living in households experiencing material hardship whereas 20.2% of Māori and 24% of Pacific children were living in households experiencing significant restrictions or deprivations of essential items (Figure 13). These disparities were even more marked for severe material hardship, when households go without nine or more essentials. In 2020/21, 9.5% of Māori children and 10.6% of Pacific children were living in households experiencing severe material hardship, compared to 3.5% of European children (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Children in low-income households, and children in households experiencing material hardship and severe material hardship, by ethnicity, Aotearoa 2020/21

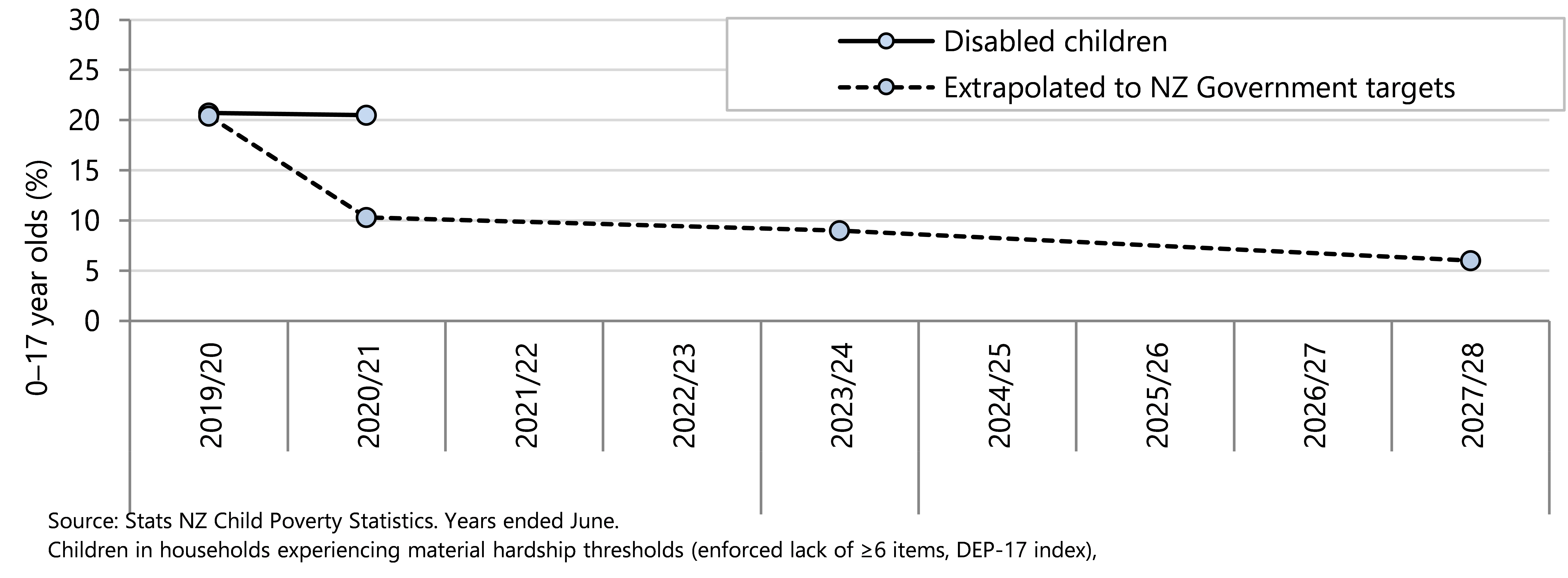

On all primary measures a higher proportion of disabled children, and children living in a household with at least one disabled person, experienced household-level low income and material hardship compared with non-disabled children and children living in households where no member was disabled (Figure 14). Children aged 2–4 years are disabled if they have serious difficulty with at least one of the following: seeing (even with glasses), hearing (even with hearing aids), walking, manual dexterity, communicating, learning, playing or controlling their own behaviour. For older children, further difficulties are added, including: difficulty feeding or dressing themselves, remembering or concentrating, accepting change, making friends, anxiety, or depression. Adults aged over 18 years are disabled if they have at least one of the difficulties already mentioned or have difficulties with upper body strength or manual dexterity. Children aged under 2 years are not assessed for disability.19

In 2020/21, 15.5% of disabled children, and 17.3% of children living in a disabled household, were in households with median equivalised disposable income before housing costs below 50% of the contemporary median (2020/21 target is 10.5%). At this same time, 17.6% of disabled children, and 18.8% of children living in a disabled household, were in households with equivalised disposable income after housing costs below 50% of the fixed-line median.

One in five disabled children (20.5%) live in households experiencing material hardship, which is more than double the rate for non-disabled children (9.7%) (Figure 14). Severe material hardship is experienced by 10.3% of children who are disabled, or by those living in a household with a disabled person, compared to much lower rates of severe material hardship experienced by non-disabled children (4.2%), and those living in a non-disabled household (2.5%) (Figure 14).19

Figure 14. Children in low-income households, and children in households experiencing material hardship and severe material hardship, by disability status, Aotearoa 2020/21

Households that pay rent experience much higher proportions of income poverty and material hardship than those who own their own homes, (with or without a mortgage).

In 2020/21, 20% of children living in households that pay rent were in low-income households with equivalised disposable income before housing costs below 50% of the contemporary median, compared to 7.5% of households who were living in their own dwelling and making mortgage payments. Similarly, 24.6% of children who live in households paying rent had an equivalised disposable income after housing costs below 50% of the fixed-line median, compared with 11.6% of those households living in their own home (Figure 15).19

Over the same time-frame, 22% of households who pay rent were also experiencing material hardship, compared to other kinds of households, who had rates of material hardship of less than 5%. More than 10% of households with children who were paying rent experienced severe material hardship in 2020/21, while this proportion was less than 1% of those households with children living in their own homes (Figure 15).19

Figure 15. Children in low-income households, and children in households experiencing material hardship and severe material hardship, by housing tenure, Aotearoa 2020/21

It is acknowledged that low-income and material hardship rates do not necessarily result in children being deprived of a ‘good life’ - many children growing up in hardship experience love and support from their whānau, families and aiga around them. However, missing out on essentials can make children sick, affect their education, and have long term impacts on their lives. A much more targeted effort will be needed to get fair and just outcomes for all children. Strong policy and practice initiatives are needed for every child in Aotearoa to have the resources that they need to thrive. From 2018/19 to 2020/21 the proportion of European children living below the poverty line (defined as less than 50% of the fixed-line median equivalised household income after housing costs) was already below the 2020/21 target (Figure 16).

Figure 16. European children in low-income households extrapolated to Government targets Aotearoa 2018/19 extrapolated to 2027/28

This intermediate target has now also been met for Māori children (Figure 17) and Pacific children (Figure 18), (2020/21 fixed-line target <50% median AHC).

However, the intermediate target for the before housing cost poverty measure (10.5% at June 2021) has not been met either overall (13.6%) or for any cohort described below.

Policy and practice resulted in no change from 2018/19 to 2020/21 in the percentages of Māori children living in households with equivalised disposable income below 50% of the contemporary median before housing costs (Figure 17), while there was a slight reduction in the proportion of Pacific children living in these households (Figure 18).

Data for disabled children were provided for the first time in the 2019/20 child poverty statistics. As shown in Figure 19, the proportions of disabled children living in low income households before housing costs is well above the 2020/21 Government target.

Figure 17. Māori children in low-income households extrapolated to Government targets Aotearoa 2018/19 extrapolated to 2027/28

Figure 18. Pacific children in low-income households extrapolated to Government targets Aotearoa 2018/19 extrapolated to 2027/28

Figure 19. Disabled children in low-income households extrapolated to Government targets 2027/28 Aotearoa

Household levels of material hardship for Māori children, Pacific children, and disabled children are all well above the 2020/21 targets (Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22).

Figure 20. Māori children in households experiencing material hardship against government targets Aotearoa 2018/19 extrapolated to 2027/28

Figure 21. Pacific children in households experiencing material hardship, extrapolated to NZ Government targets, Aotearoa 2020/21 extrapolated to 2027/28

Figure 22. Disabled children in households experiencing material hardship, extrapolated to NZ Government target, Aotearoa 2020/21 extrapolated to 2027/28

How is hardship experienced?

In the year ended June 2021, 11% of children live in households experiencing material hardship – households that cannot afford specific items that most people regard as essential.

Households in hardship prioritise their basic needs differently than those not experiencing hardship. Less than one percent of children living in households that are not in material hardship are deprived of meals with a protein component, lack two pairs of shoes or go without fresh fruit and vegetables. Less than ten percent of households that are not in hardship are limited in purchasing adequate meat and clothing. The great majority (95% or more) of households that are not in hardship report they can give presents on special occasions, are able to go on local trips, replace broken appliances and do not need to put up with being cold.

In contrast, while most children in households experiencing hardship are still provided with meals containing protein, and have two pairs of shoes, almost a quarter report they go without fresh fruit and vegetables, and approximately 70% restrict meat in meals. Nearly 40% of households in hardship report putting up with cold, and one in four are unable to give presents on special occasions.

Almost three in four households in hardship report being very limited in their ability to purchase clothes and shoes, 61% cannot place broken appliances, and more than half cannot pay for utilities such as power or rates on time. Households experiencing hardship report being especially vulnerable to extra financial shocks, with 85% unable to pay an unexpected $500 debt, and 68% forgoing home contents insurance. Over half of these households need to borrow from friends and family in order to meet everyday costs. The percentages of children living in households going without basic needs, by material hardship status are shown in Figure 23 .

Figure 23 Children living in households going without basic needs, as measured using Dep-17 index items, by material hardship status, Aotearoa 2020/21.

How low income affects population groups

This section reports on low-income rates for households with children by region and household type, and briefly describes how material hardship is experienced by low-waged families.

These data have been collated from the child poverty statistics19 and wellbeing statistics26 collected by Stats NZ, and the original analyses describing income poverty and hardship by household type and low-waged families contained in the Child Poverty in New Zealand report from the Ministry of Social Development.20

Region

The proportions of children living in households with low income varies by region of Aotearoa, as shown in Figure 24. The regions with the highest proportions of children living in households with less than 50% median equivalised disposable income after housing cost (fixed measure) were Bay of Plenty (18.8%), Waikato (18.2%) and Northland (17.8%), while the region with the lowest rate was Southland (10.9%). However, due to the large population, the region with the largest number of children living in households experiencing income poverty was Auckland where an estimated 66,700 children are living in households with less than 50% median equivalised income (AHC), in 2020/21, (Figure 25).

Figure 24 . Percentage of children in low-income households (income less than 50% of the fixed-line median household income) after housing costs (AHC), by regional council area, Aotearoa 2020/21

Figure 25 . Number of children in low-income households (income less than 50% of the fixed-line median household income) after housing costs (AHC), by regional council area, Aotearoa 2020/21

Household type

Approximately 15% of children live in single parent households. Single parent households have rates of material hardship that are three to four times higher than those of two parent households. Out of all children in severe material hardship, 41% are from single parent households. 20 Single parents are often solely responsible for all household expenses so are less able to benefit from economies of scale. Two-parent households may also benefit from sharing childcare more flexibly, allowing greater hours of employment. While the requirement for non-custodial parents to provide financial child support is intended to offset the disadvantages of a single parent household, it rarely completely compensates.27

In Aotearoa, well-being measures from the 2021 General Social Survey (collected between April 2021-August 2021) show that sole parents are about three times more likely than parents in two-parent families to report ‘not enough money to meet everyday needs’ and nearly 40% of sole parents report low levels of life satisfaction. Nearly 46% of sole parents report poor overall mental wellbeing; this is a much higher proportion than in the whole population, of which approximately 28% report poor mental wellbeing. 26

Low-waged families

As described in the Child Poverty in New Zealand report from the Ministry of Social Development,20 about the same number of children in households in material hardship come from working households as come from beneficiary households (60000-65000 children in 2021), although beneficiary households have hardship rates that are four to five times higher than rates for children in working households. Approximately 70% of children live in two-parent households, and there is an increasing proportion of two-earners in these, which may partially reflect that a single income for a household with children is no longer viable.

Adequate financial assistance

A Government-appointed review of the welfare system in Aotearoa noted that New Zealand Social Security Act 201828 “is meant to provide a government guarantee of financial and social support to ensure people have an adequate income and standard of living when needed.” 29 (page 5) The review group recommended a social security system that restores trust and treats people with dignity.29

The following section uses data from the Ministry of Social Development to review the proportion of children included in recipients of financial assistance.

Data sources and methods

Indicator

Number of 0–17 year olds included in recipients of financial assistance

Data sources

Numerator: SWIFT database: Number of 0–17 year olds included in recipients of financial assistance

Denominator: NZCYES Estimated Resident Population

Definitions

Main benefits (up to June 2013) include: Domestic Purposes Benefit (DPB)-Care of Sick and Infirm, DPB- Woman Alone, Emergency Benefit, Independent Youth Benefit, Youth Payment, Young Parent Payment, Unemployment Benefit Training and Unemployment Benefit Training Hardship, Unemployment Benefit Student Hardship, Widow's Benefit.

Main benefits (from June 2014 onwards) include: Jobseeker Support, Sole Parent Support, and Supported Living Payment

Other benefits (from June 2014 onwards) include: Emergency Benefit, Youth Payment, Young Parent Payment, and Jobseeker Support Student Hardship.

Main benefits are income-replacing.

Not-income replacing financial assistance includes but is not limited to: Disability allowance, Unsupported Child's Benefit and Orphan's Benefit and Non-Beneficiary Assistance/Non-Benefit Assistance. 30

Non-benefit financial assistance is assistance provided to those who are not beneficiaries, such as accommodation supplements.

Hardship Assistance is the term used to describe emergency grants and one-off payments. The two main types of payment are Special Needs Grants (non-recoverable) and Advance Payments (also known as Recoverable Assistance Payments)

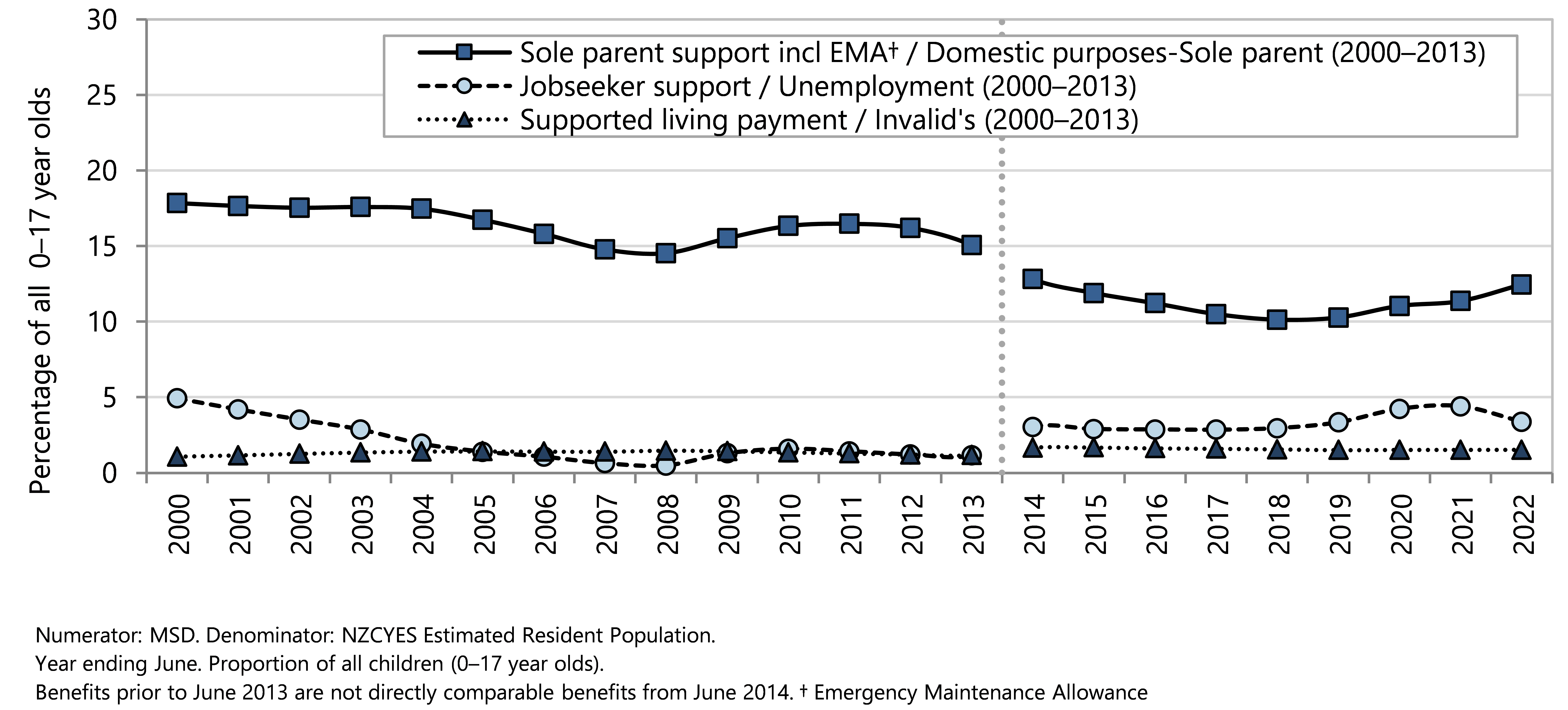

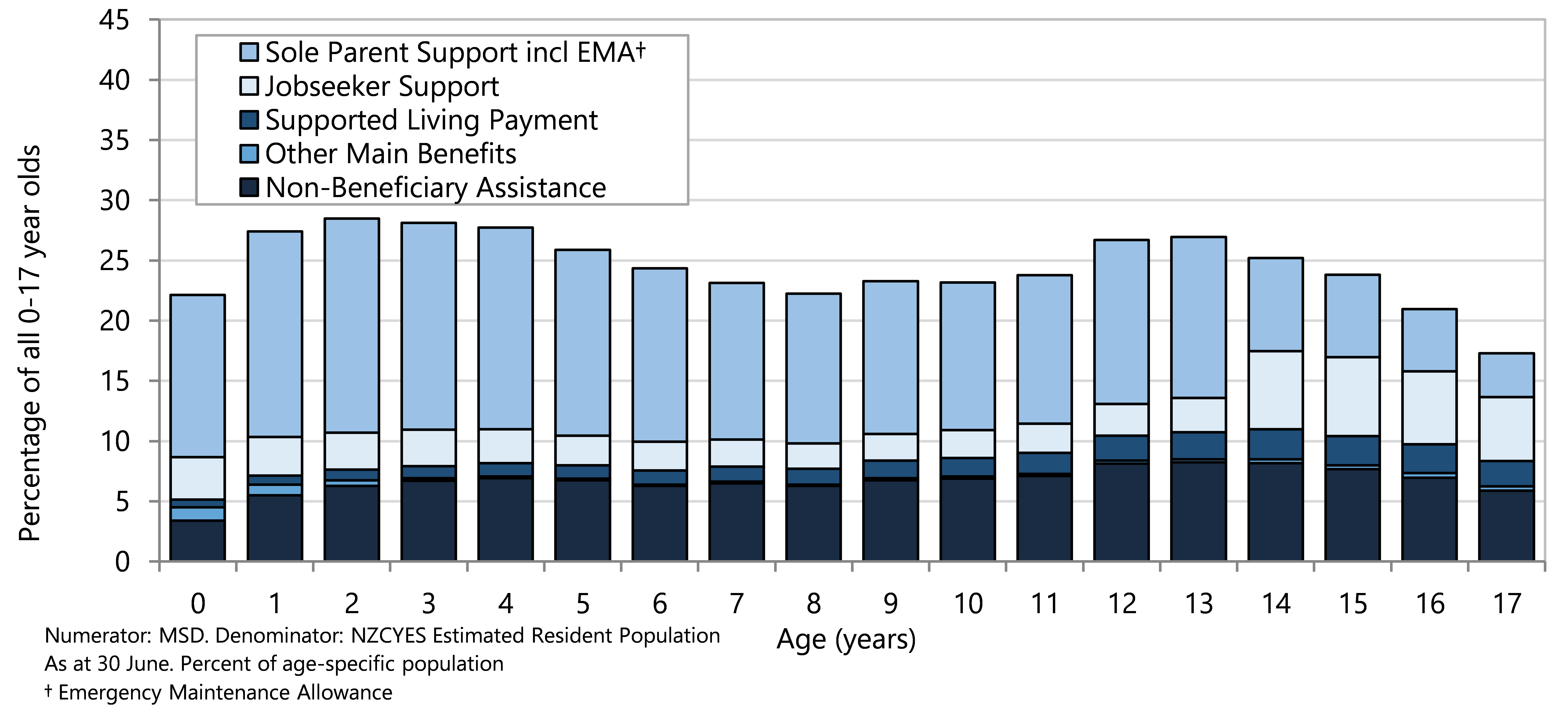

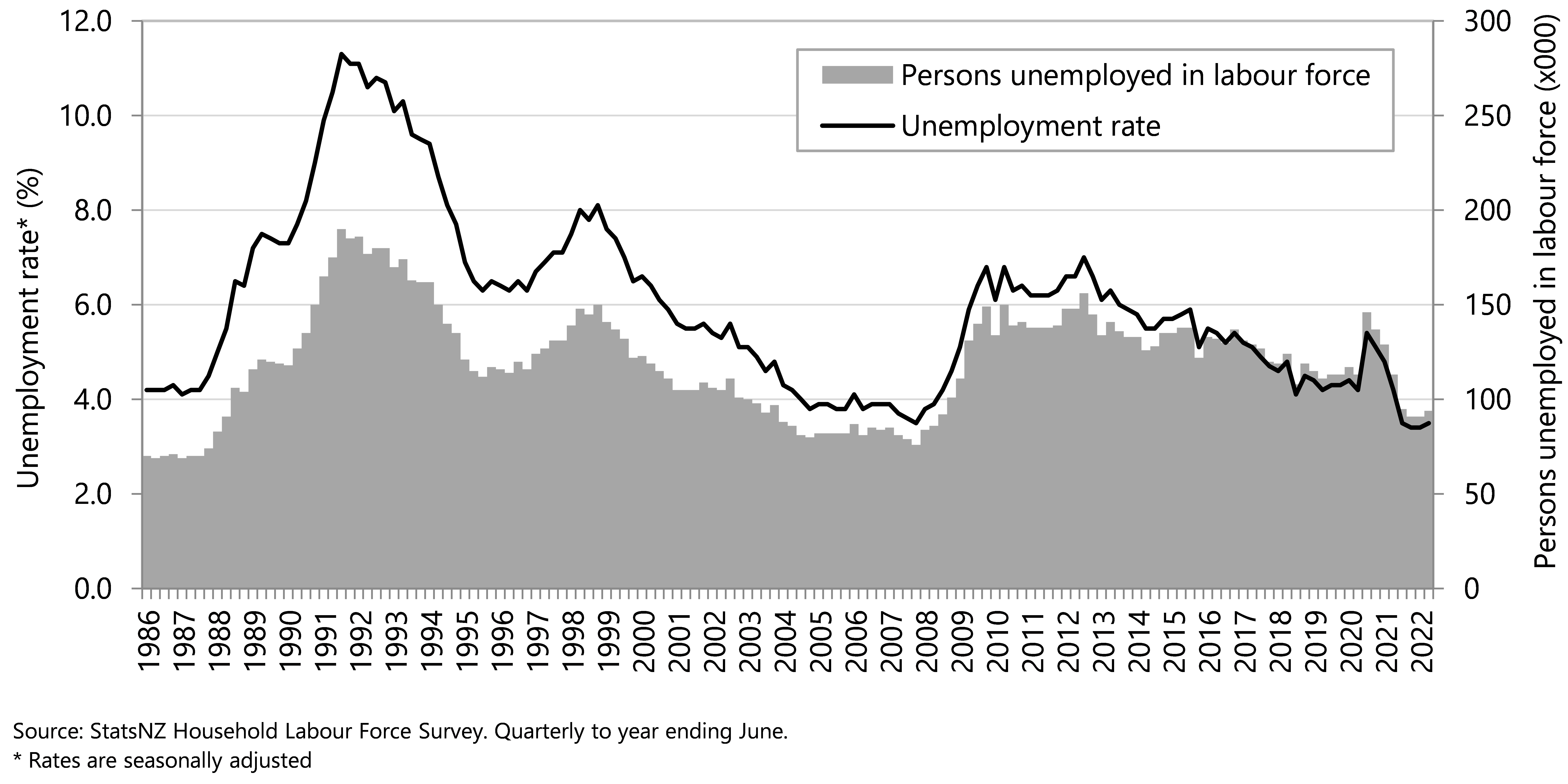

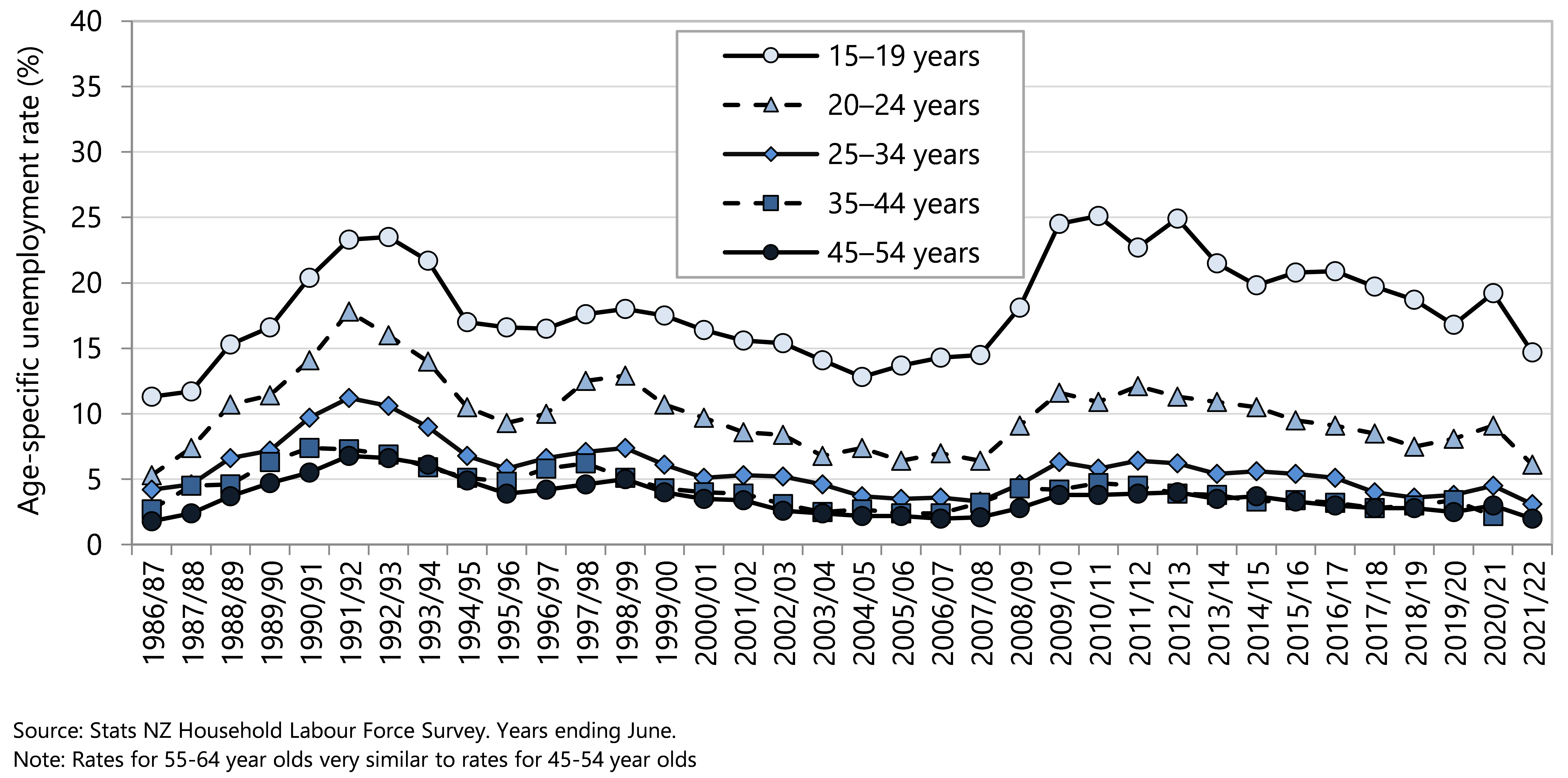

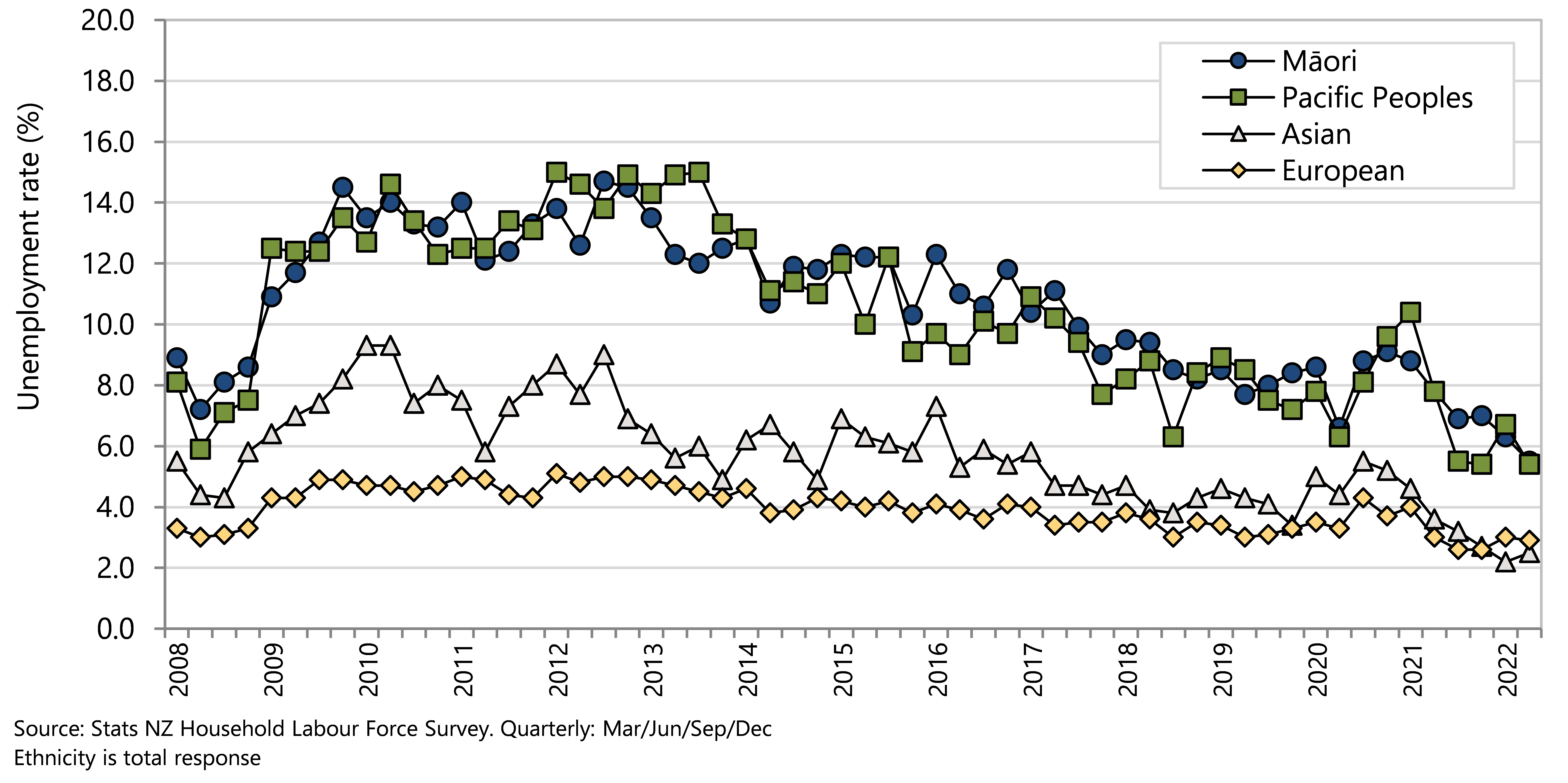

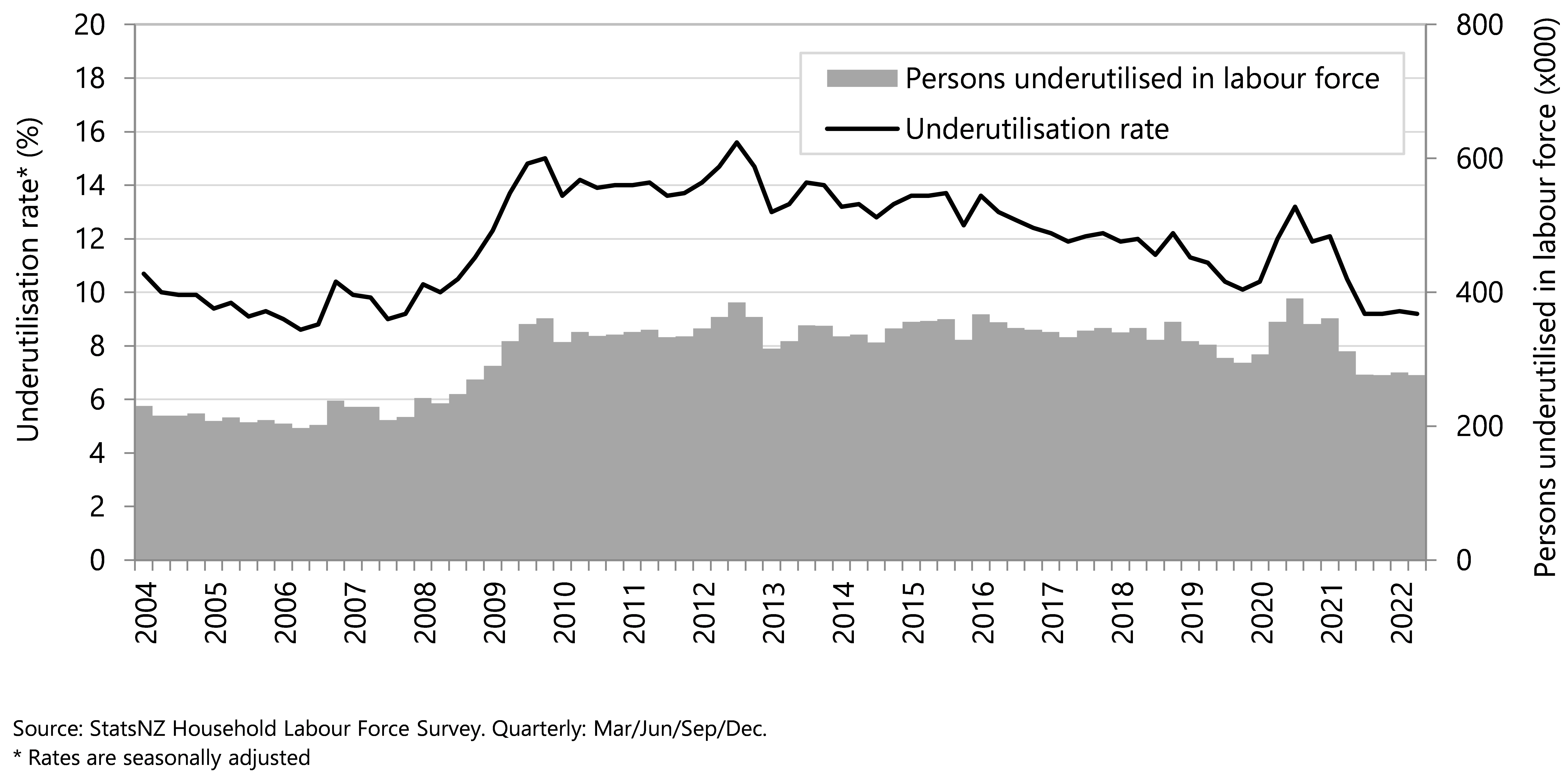

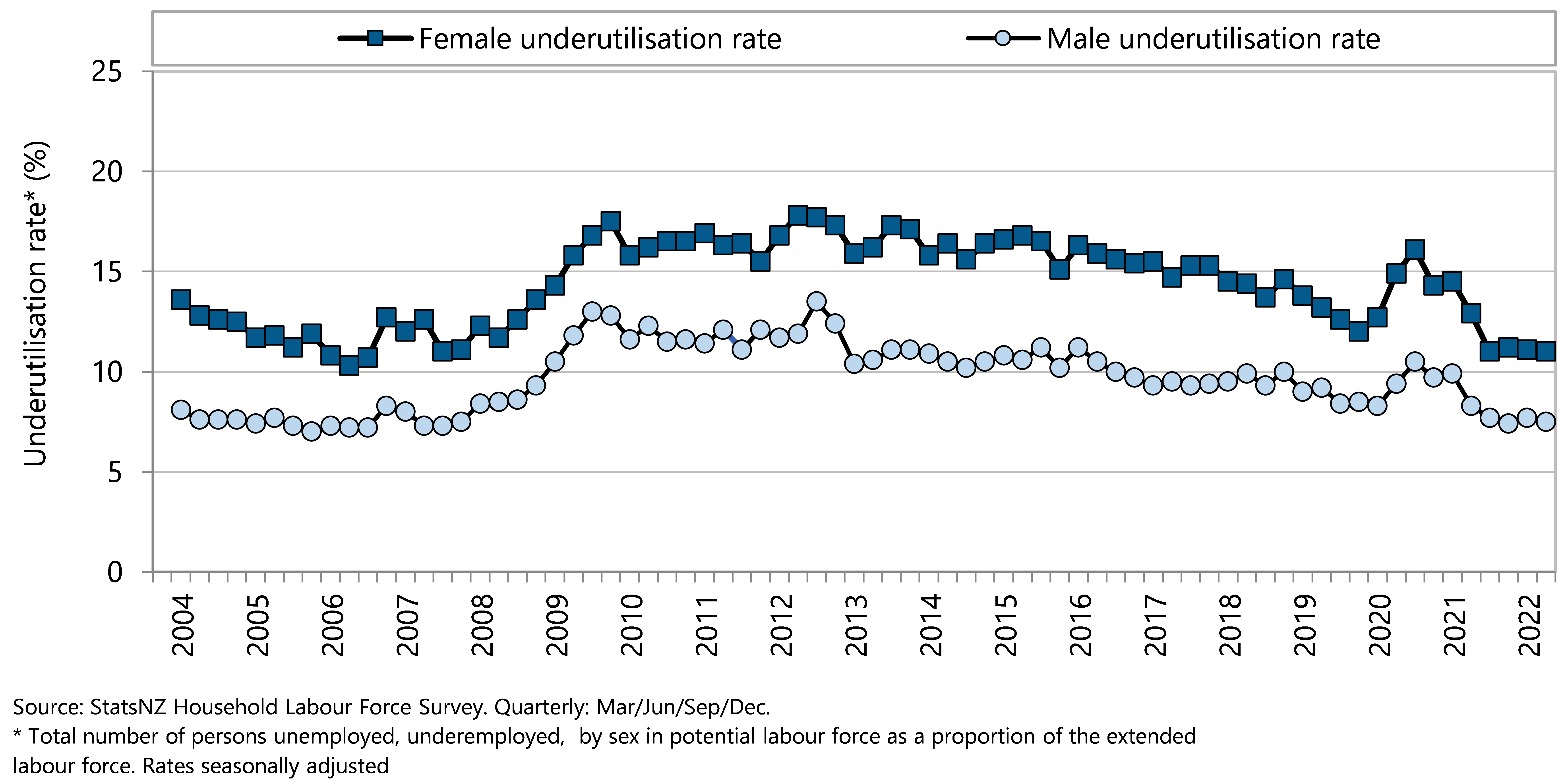

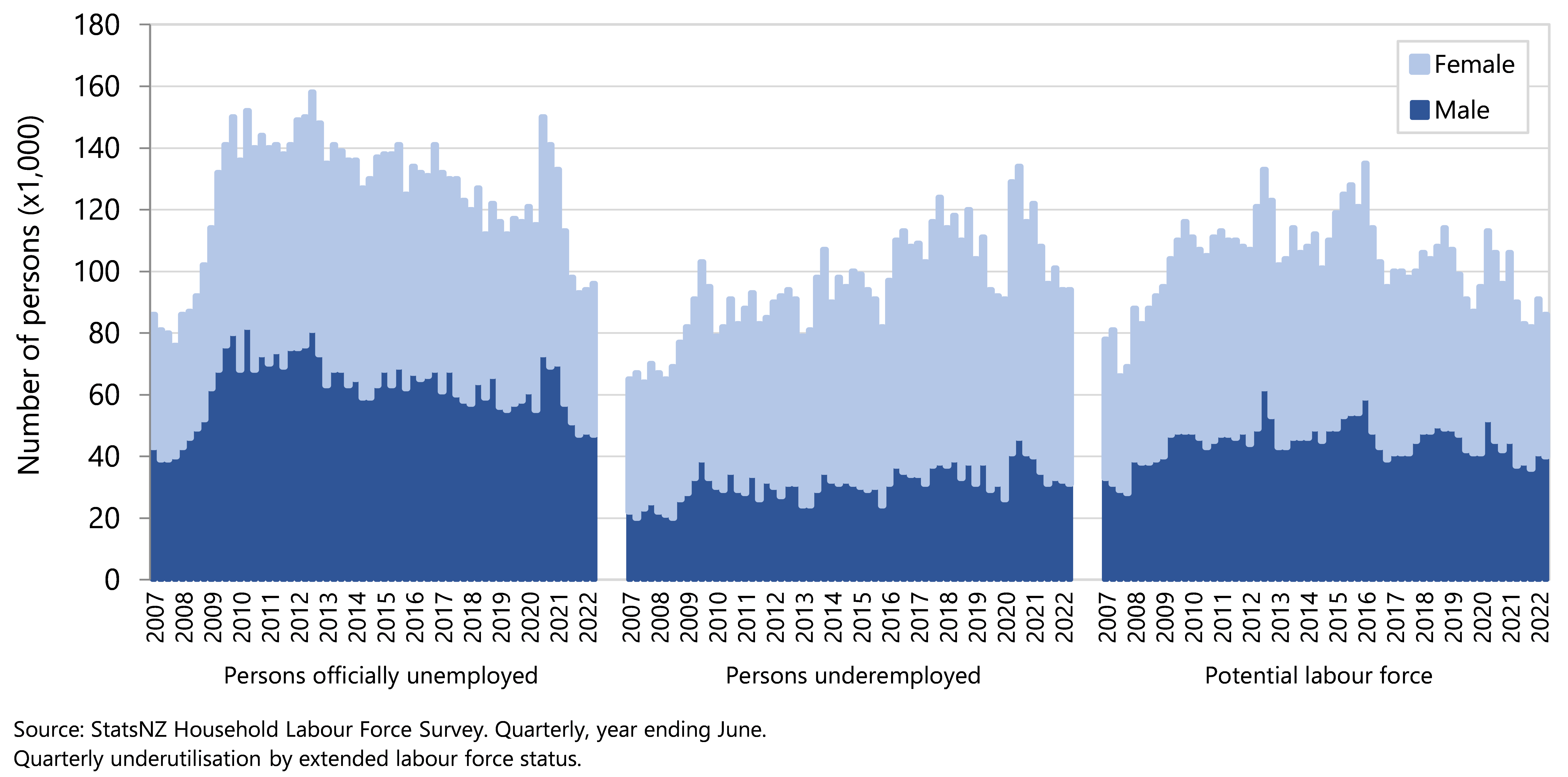

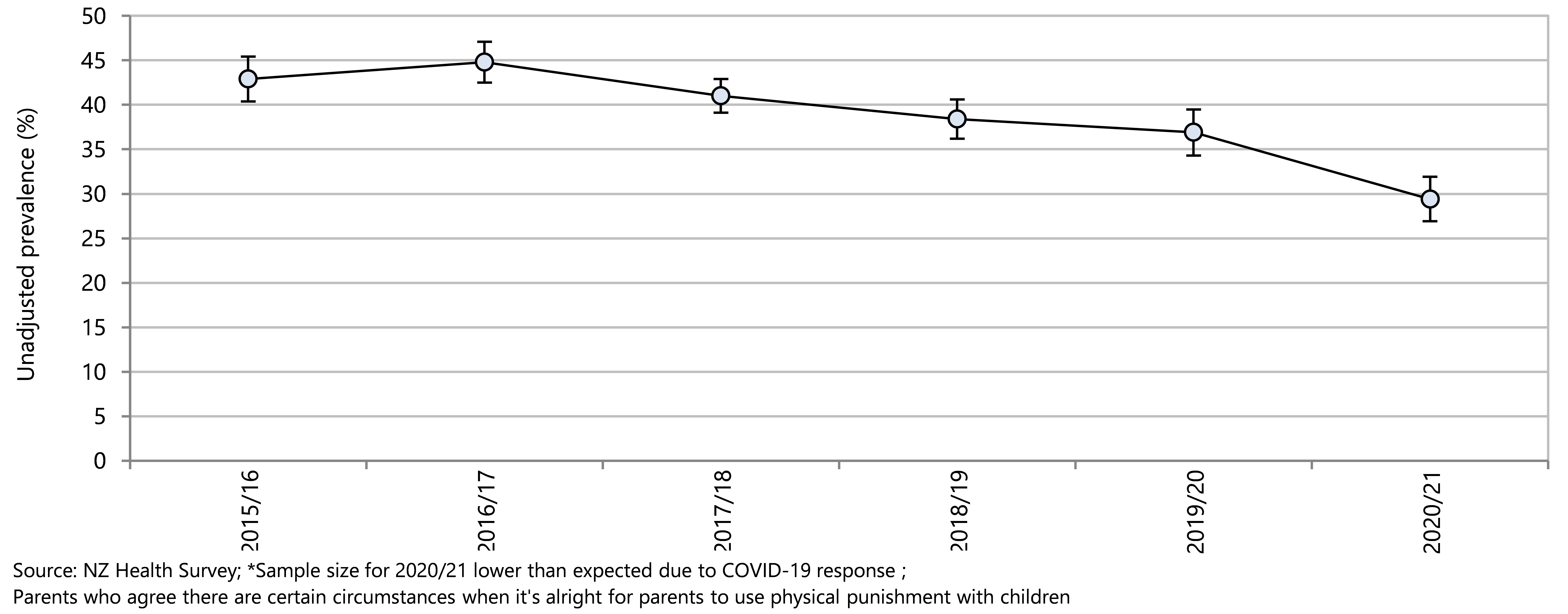

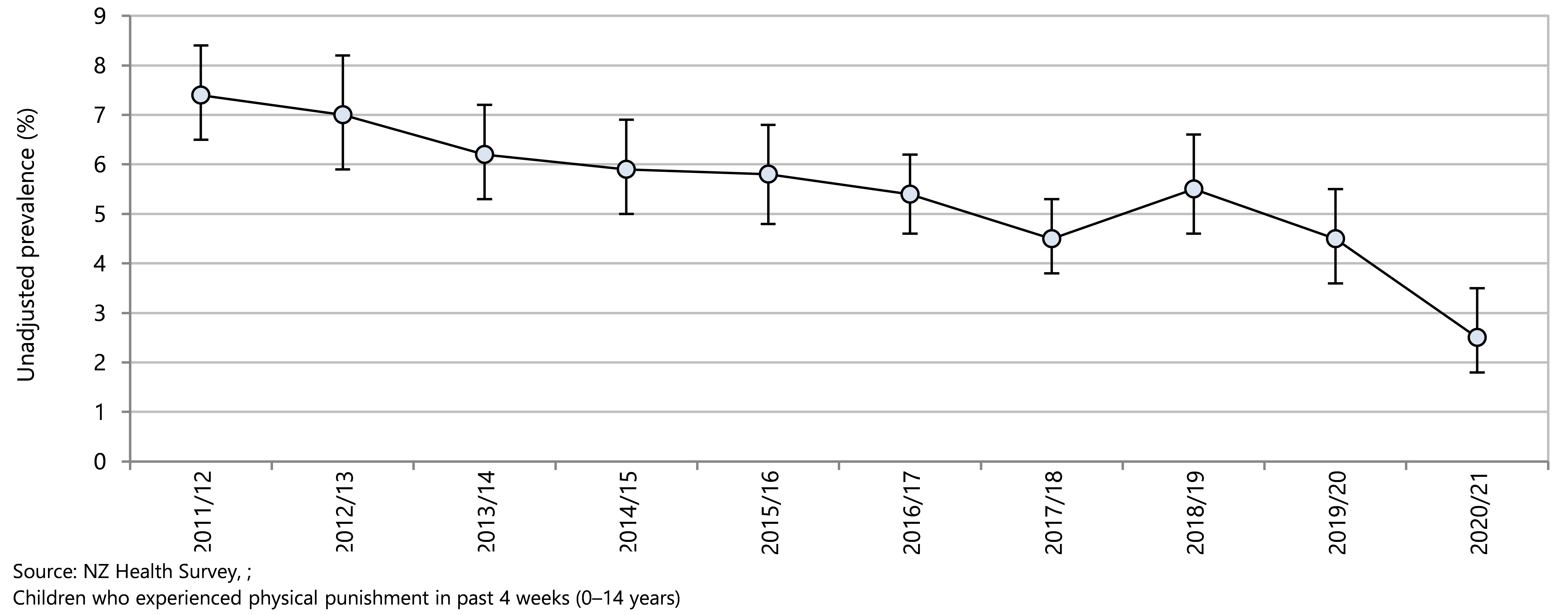

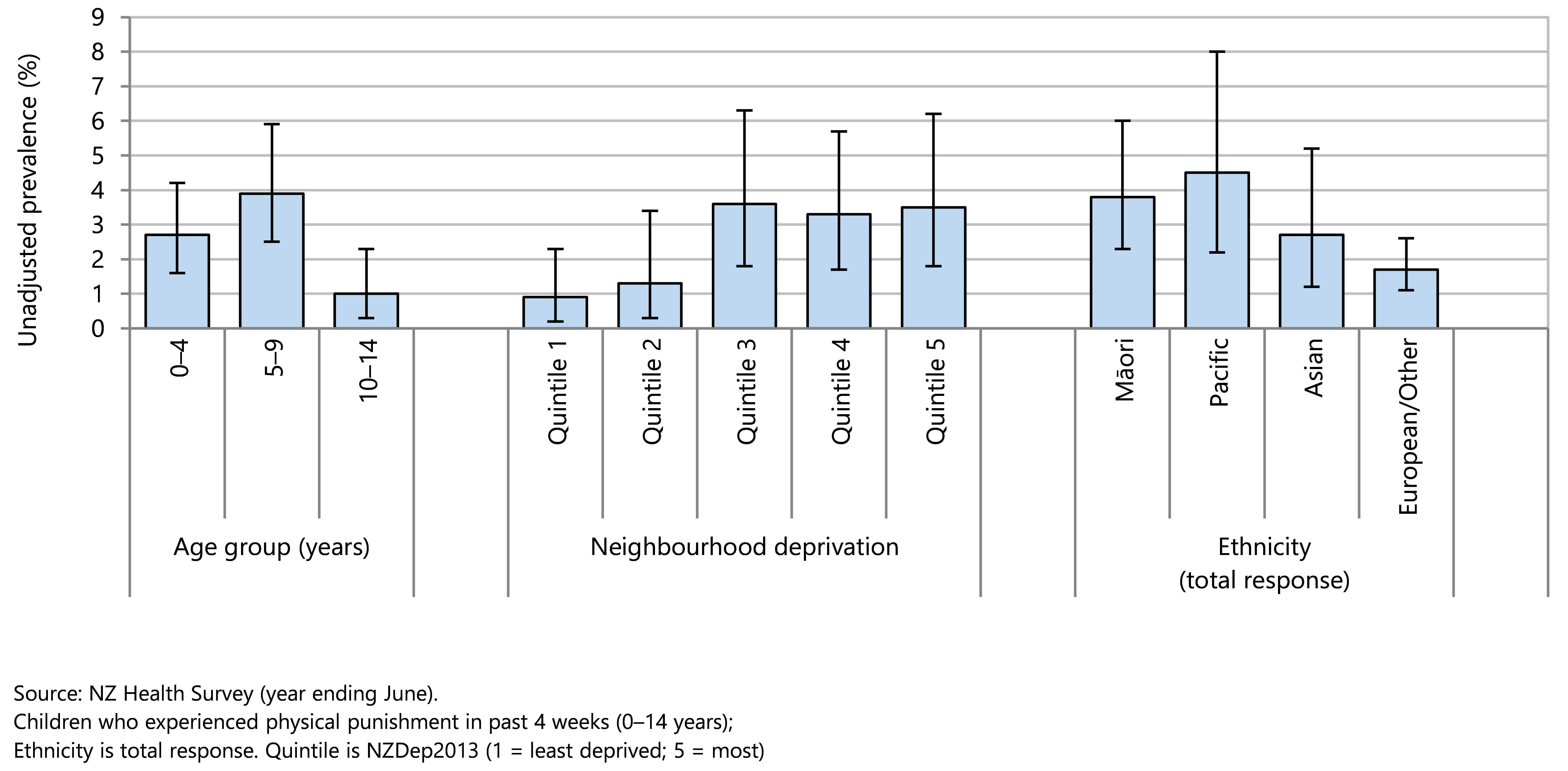

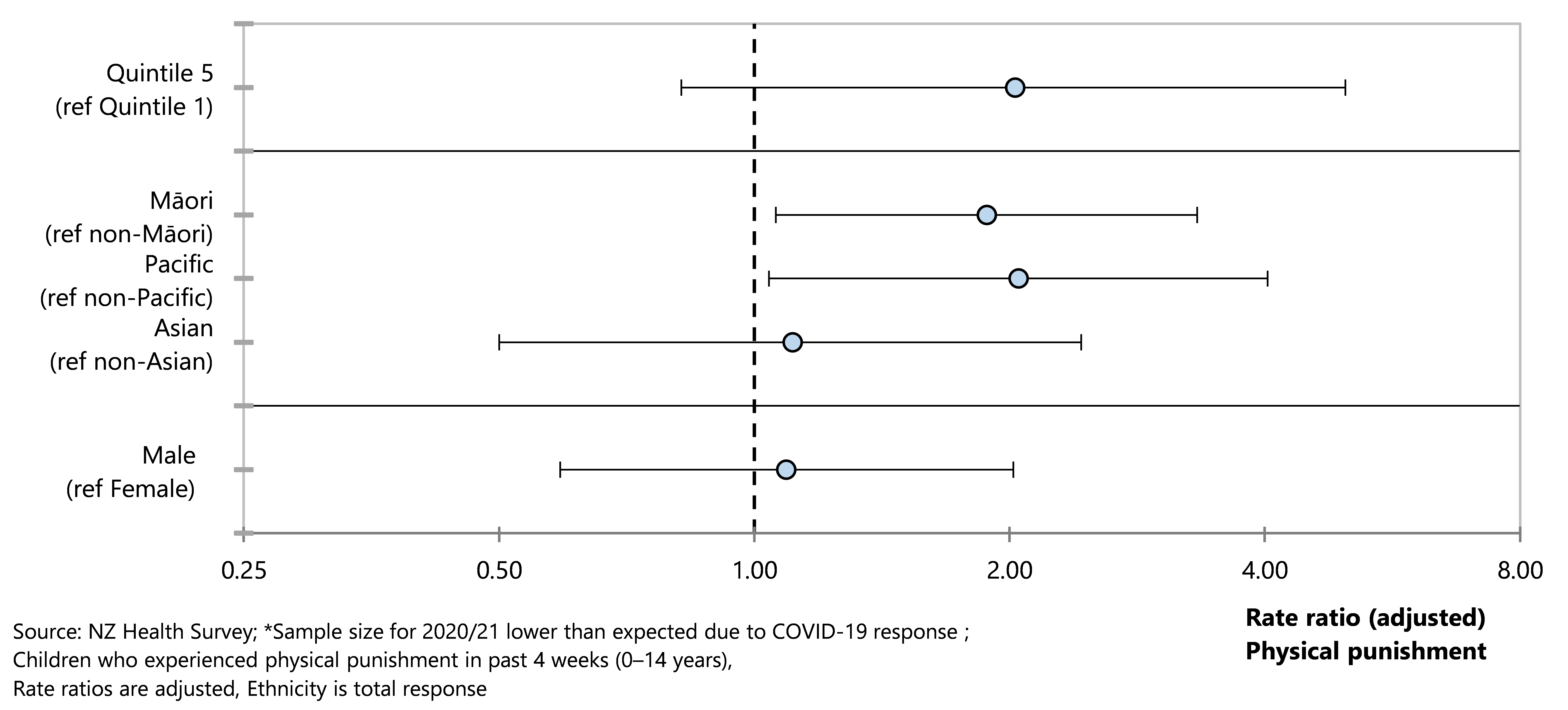

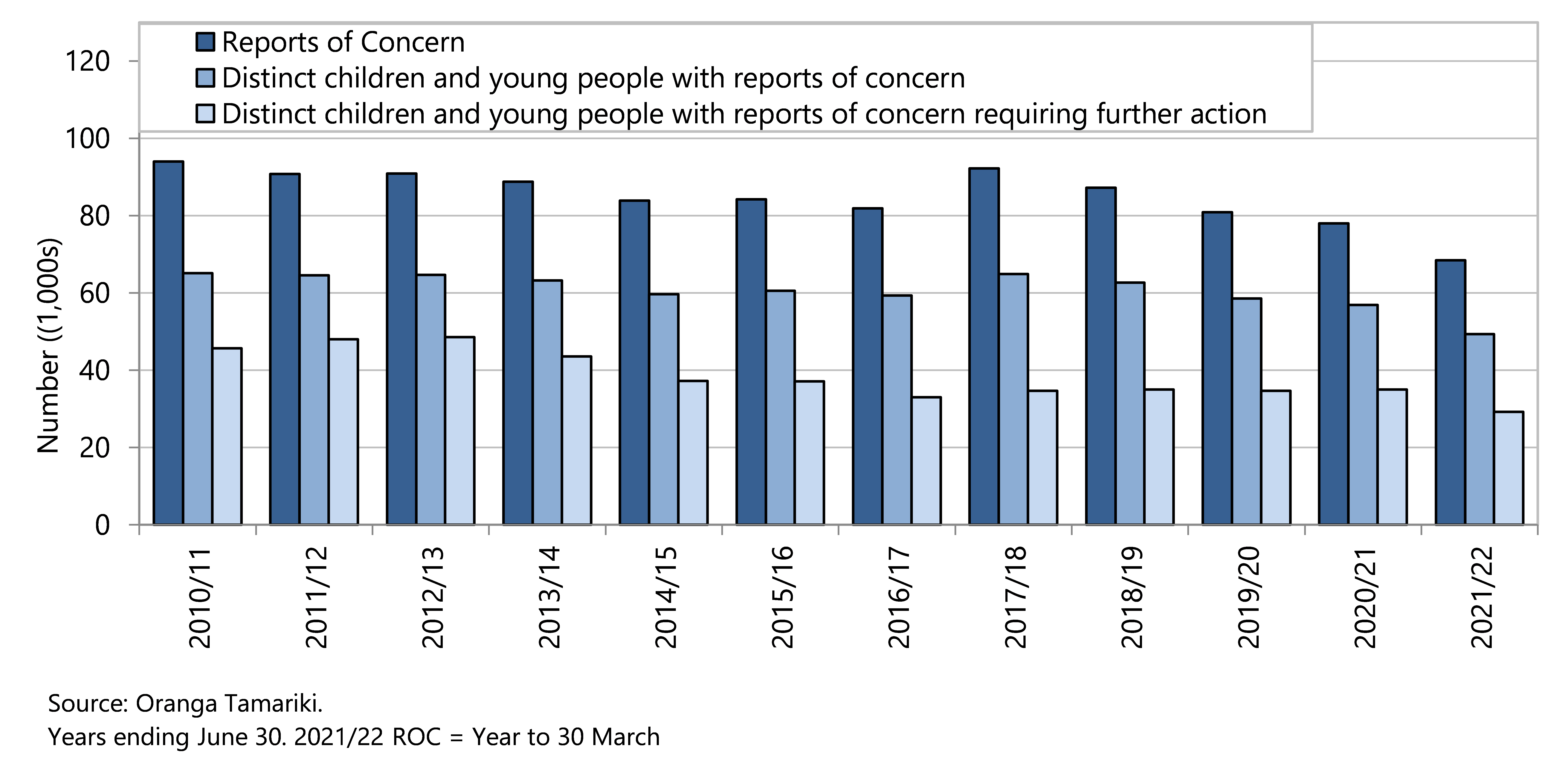

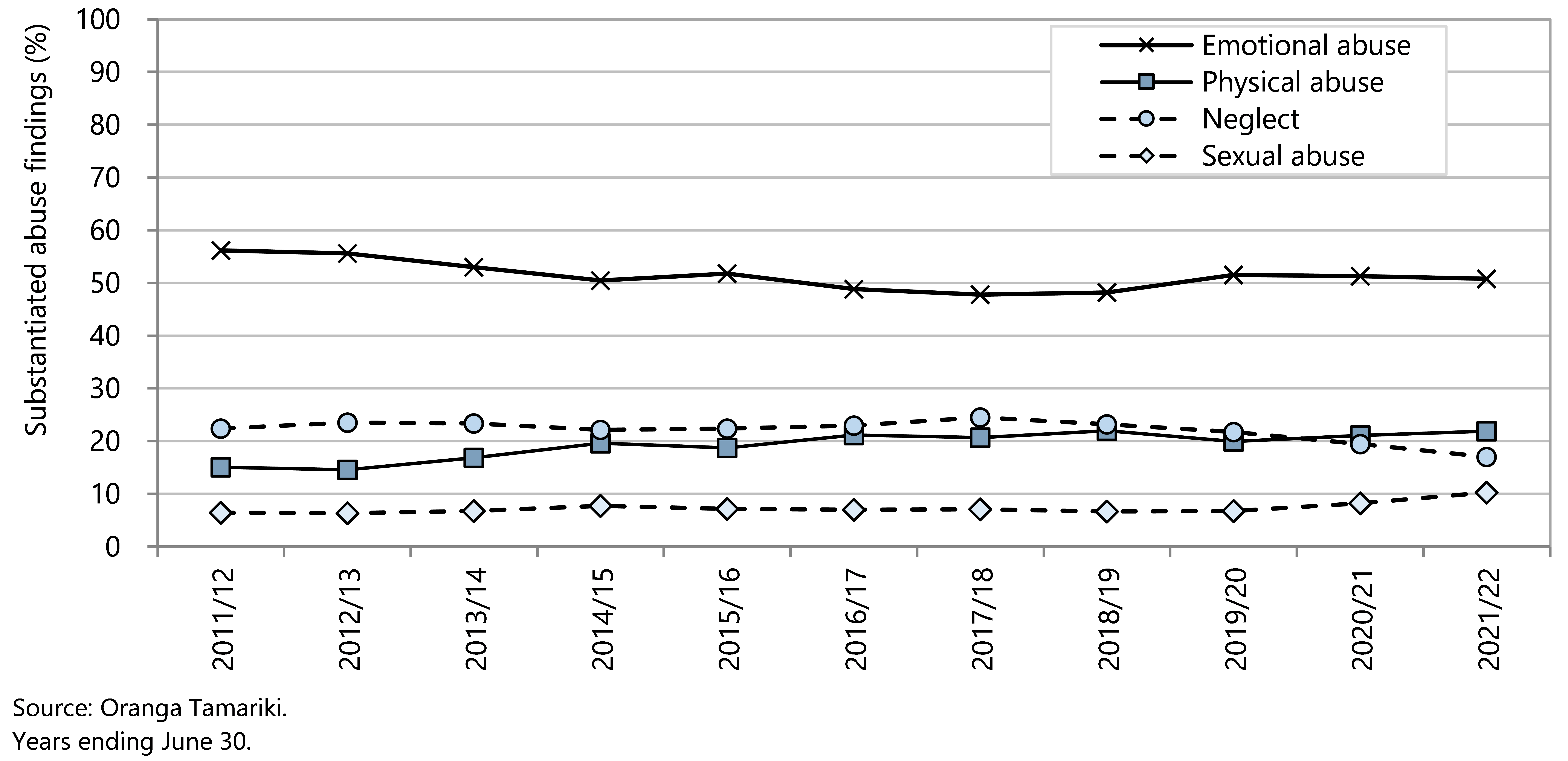

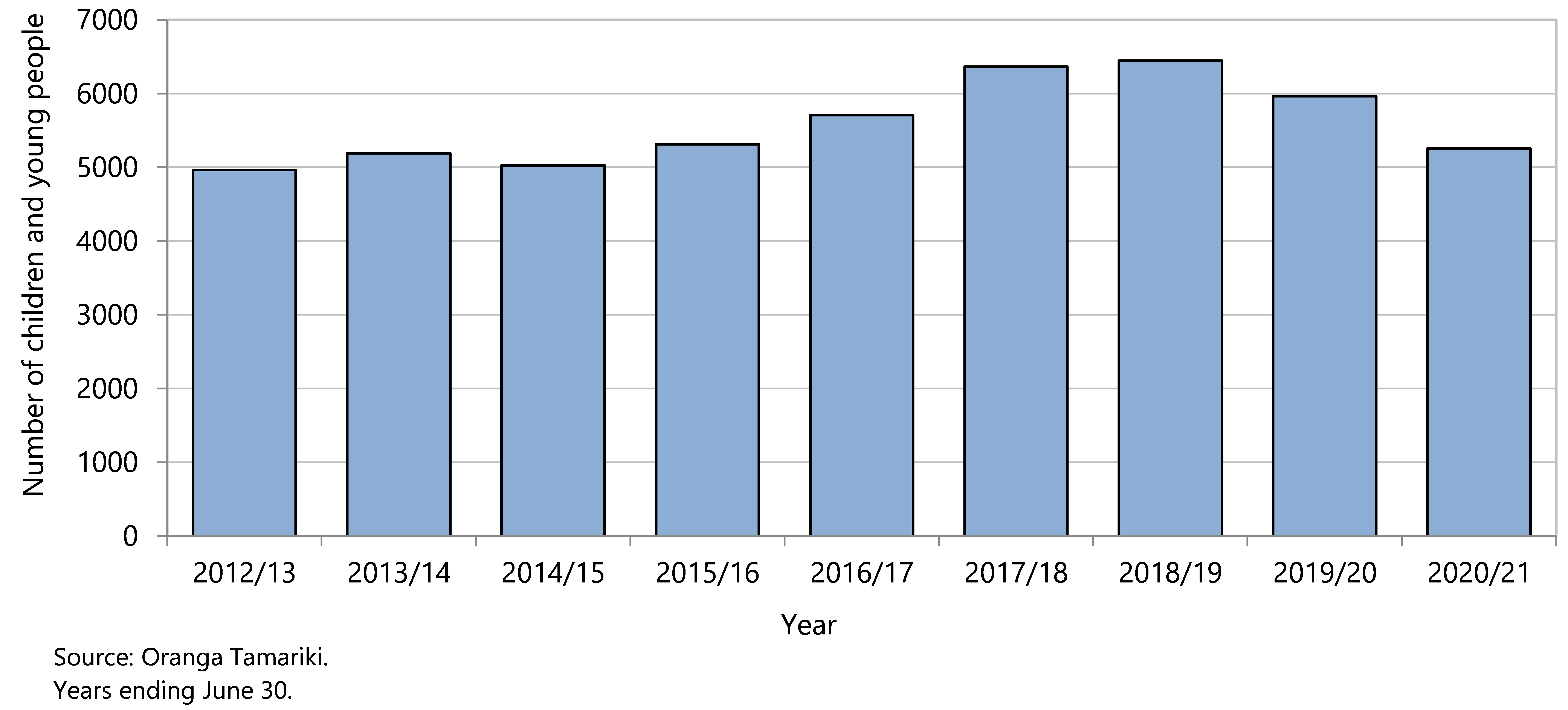

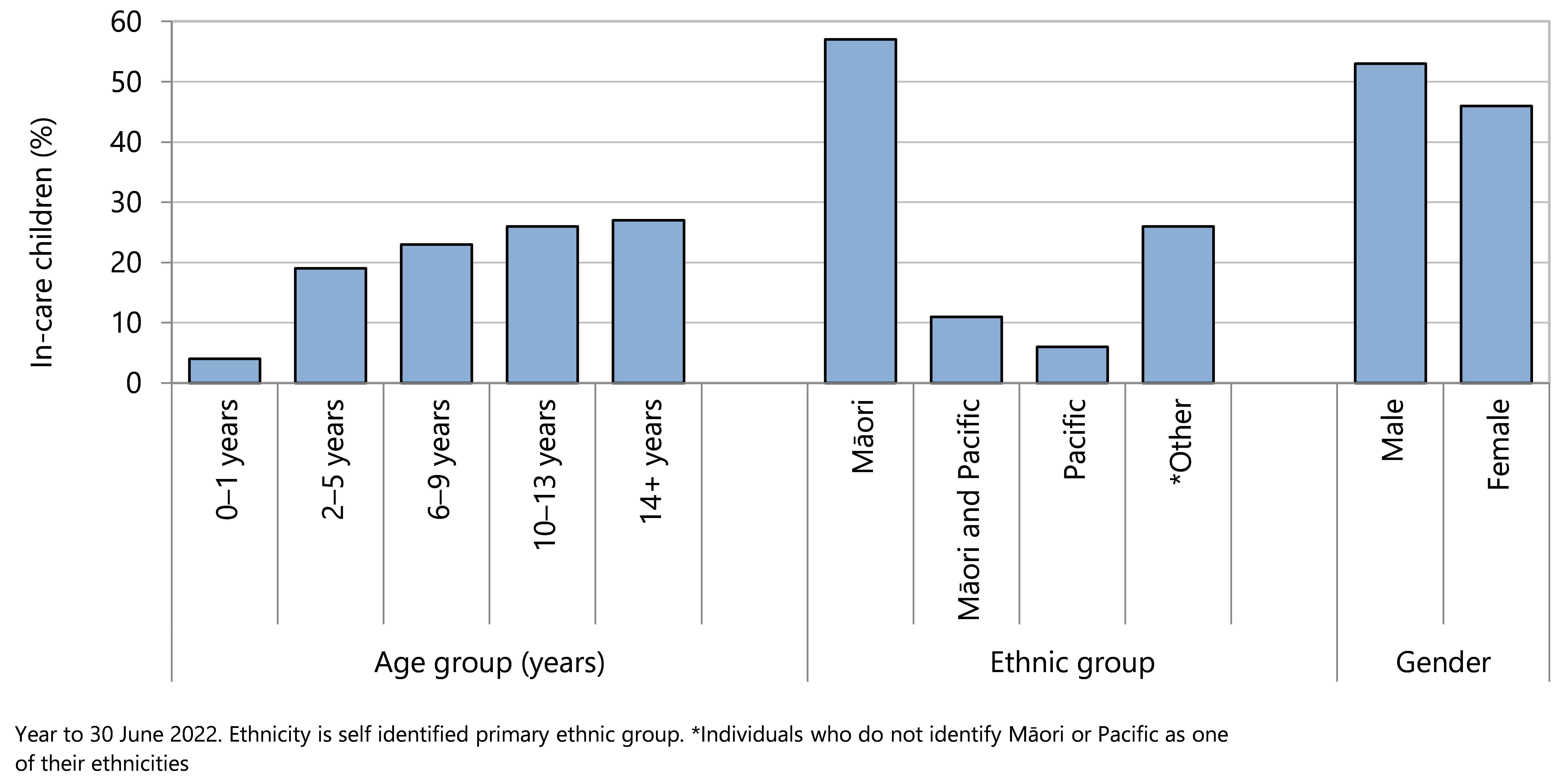

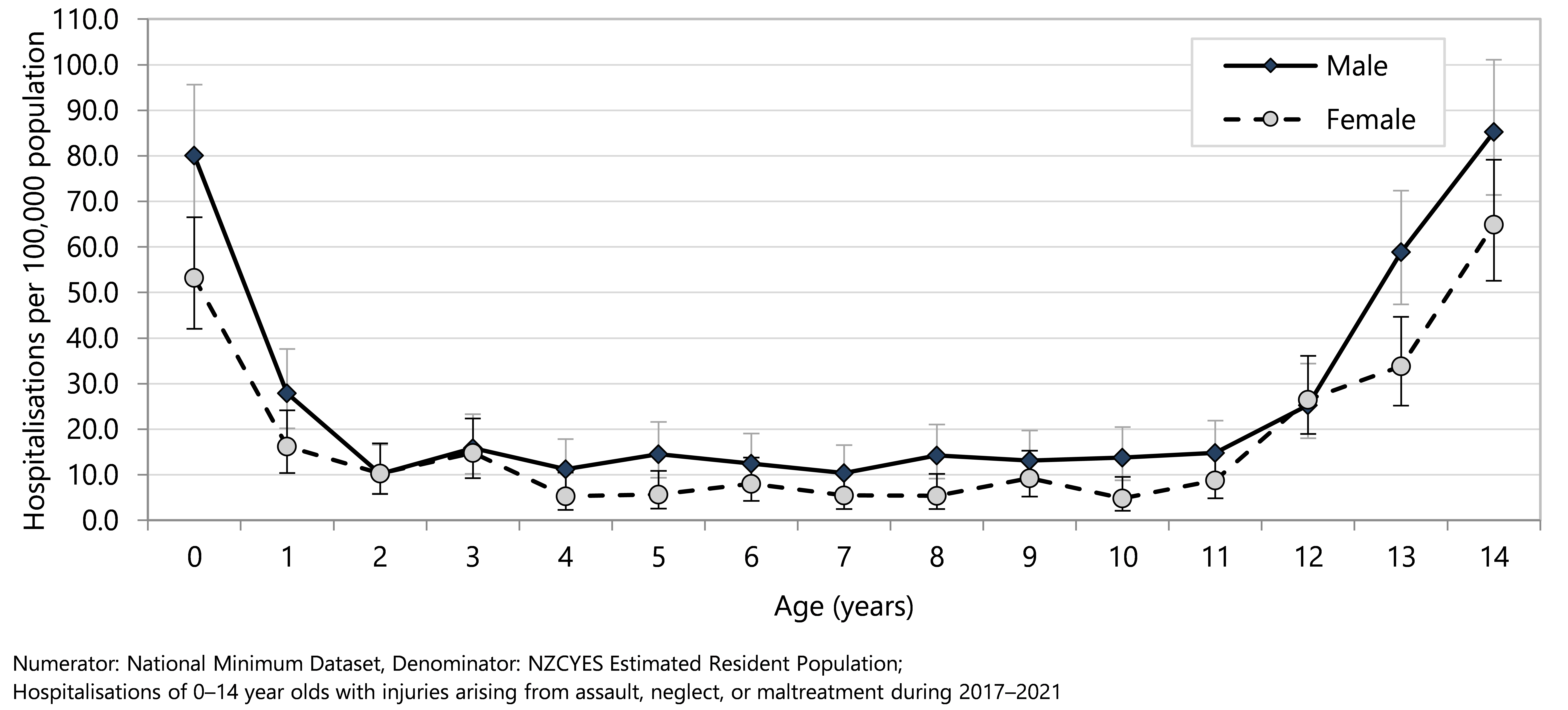

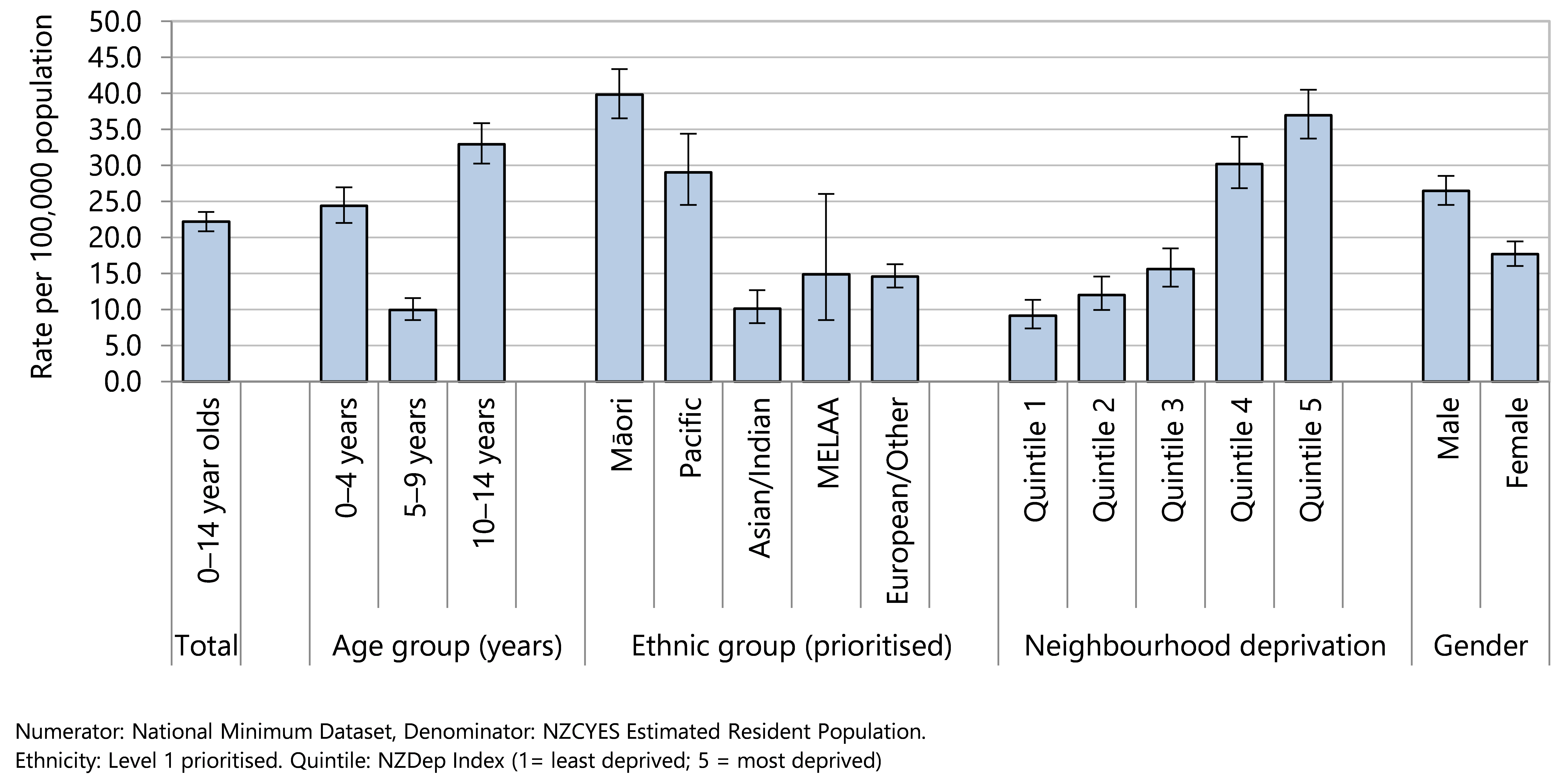

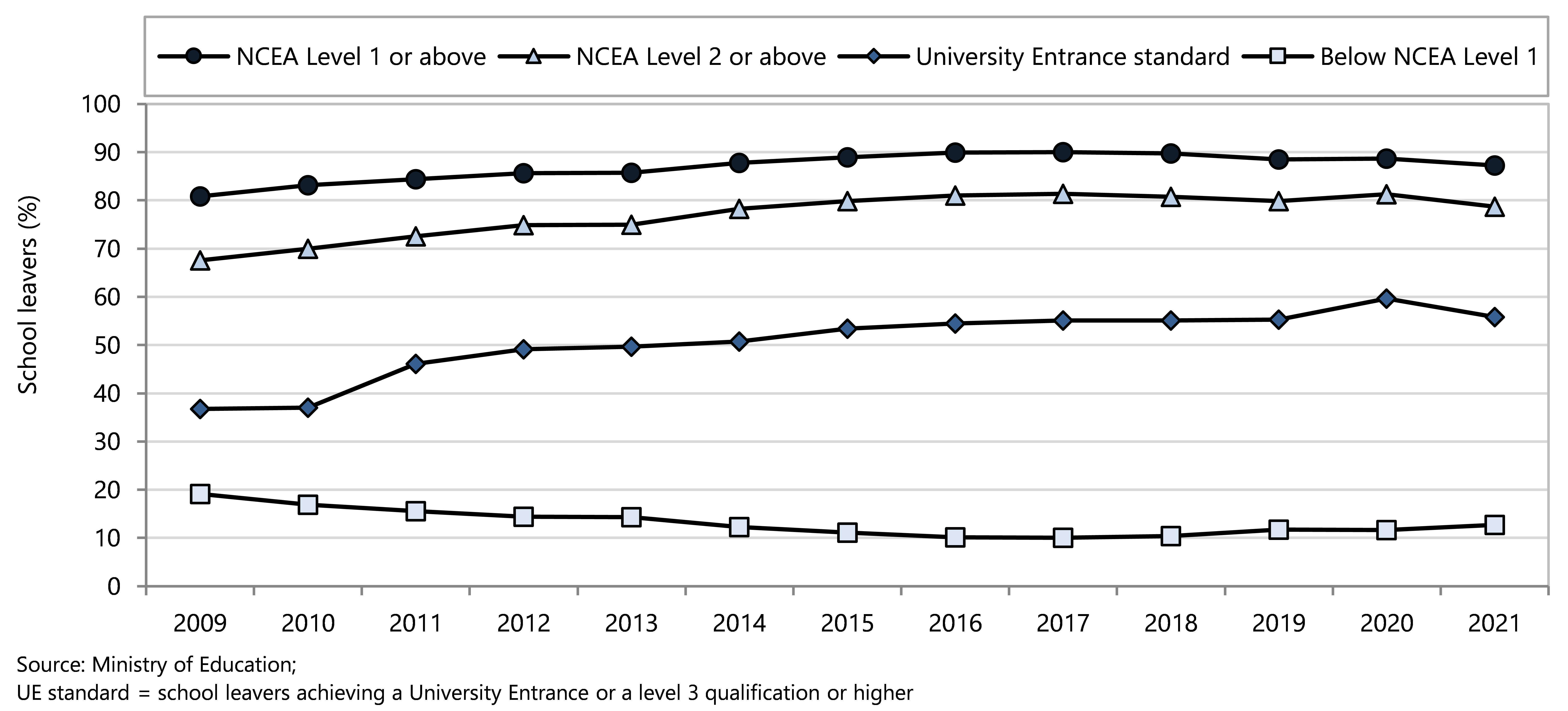

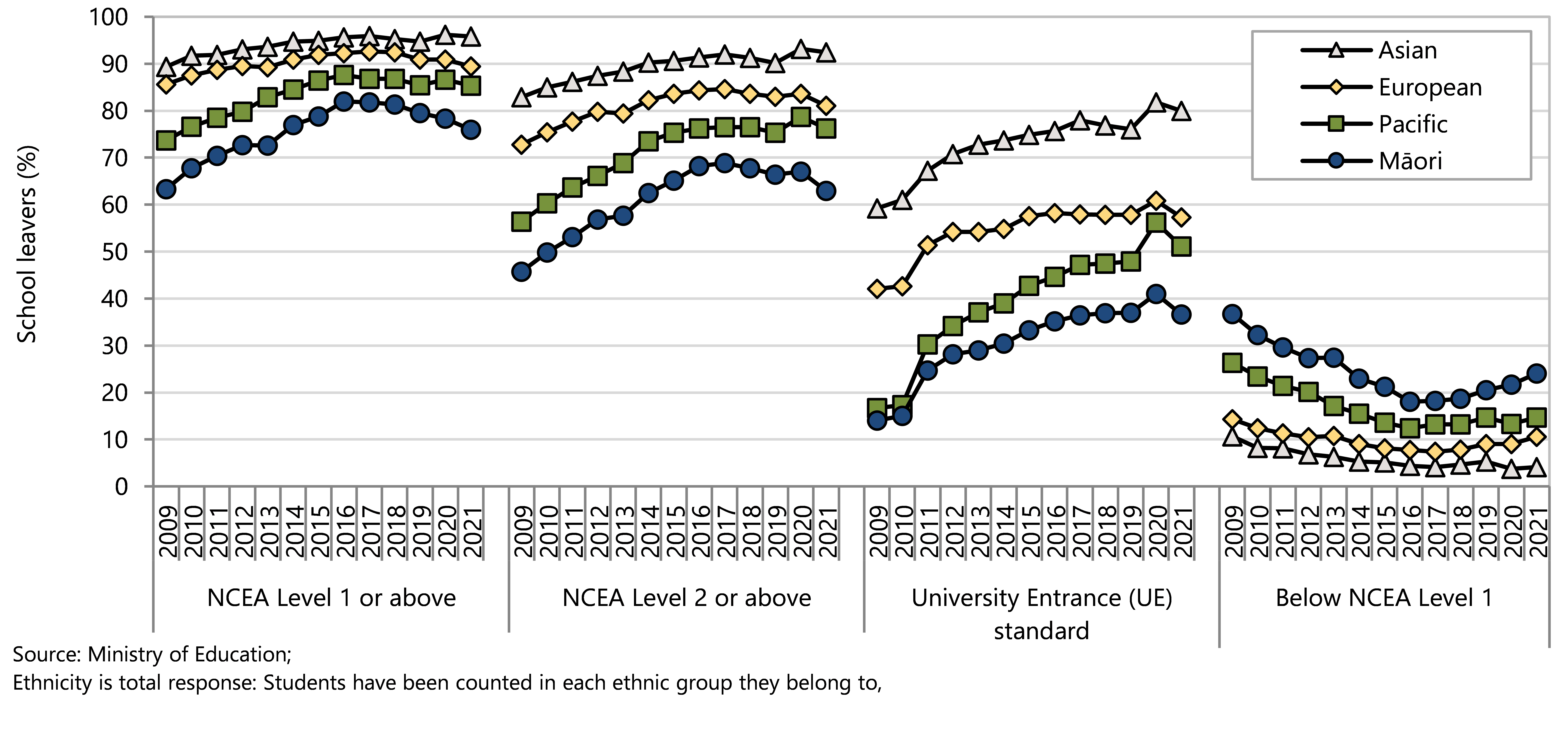

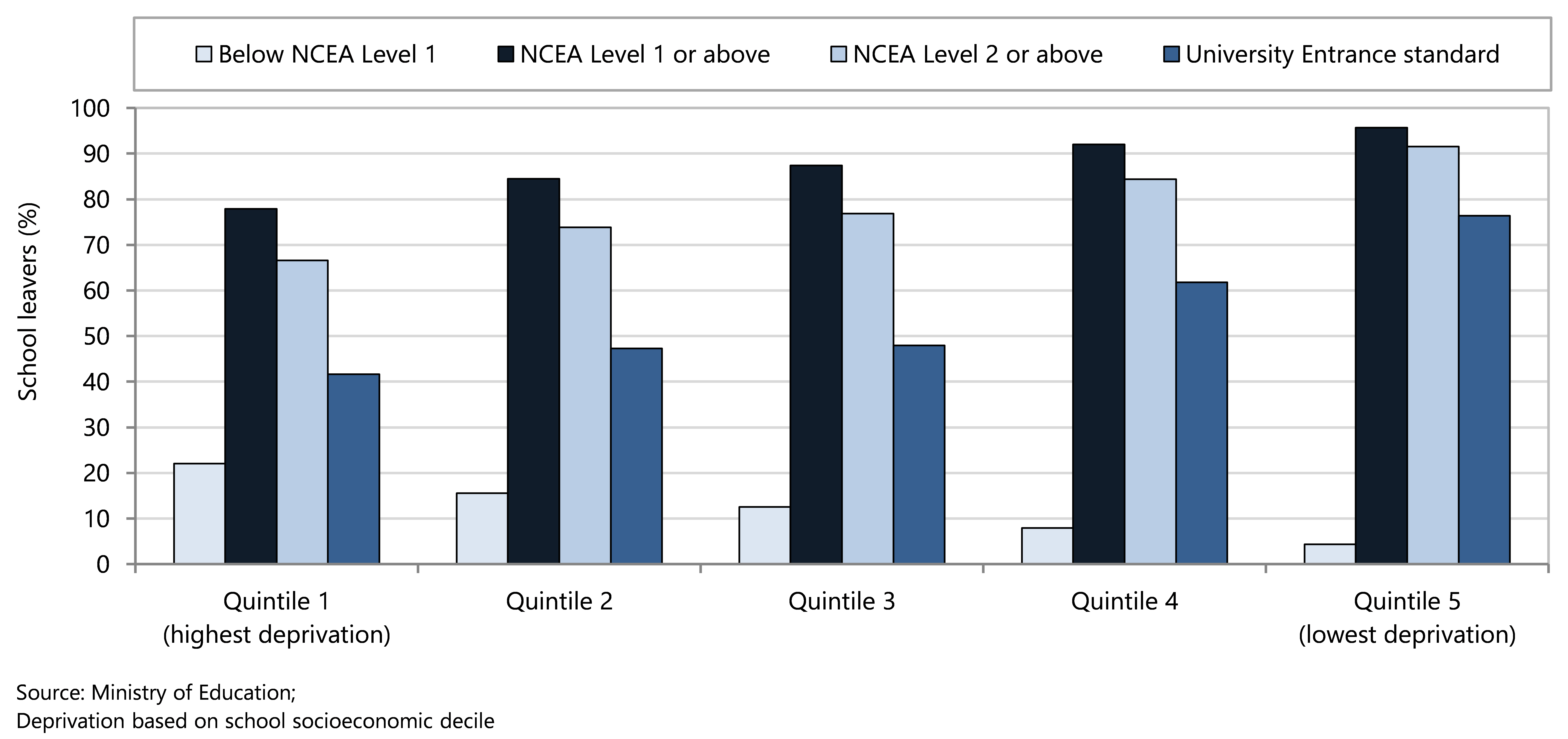

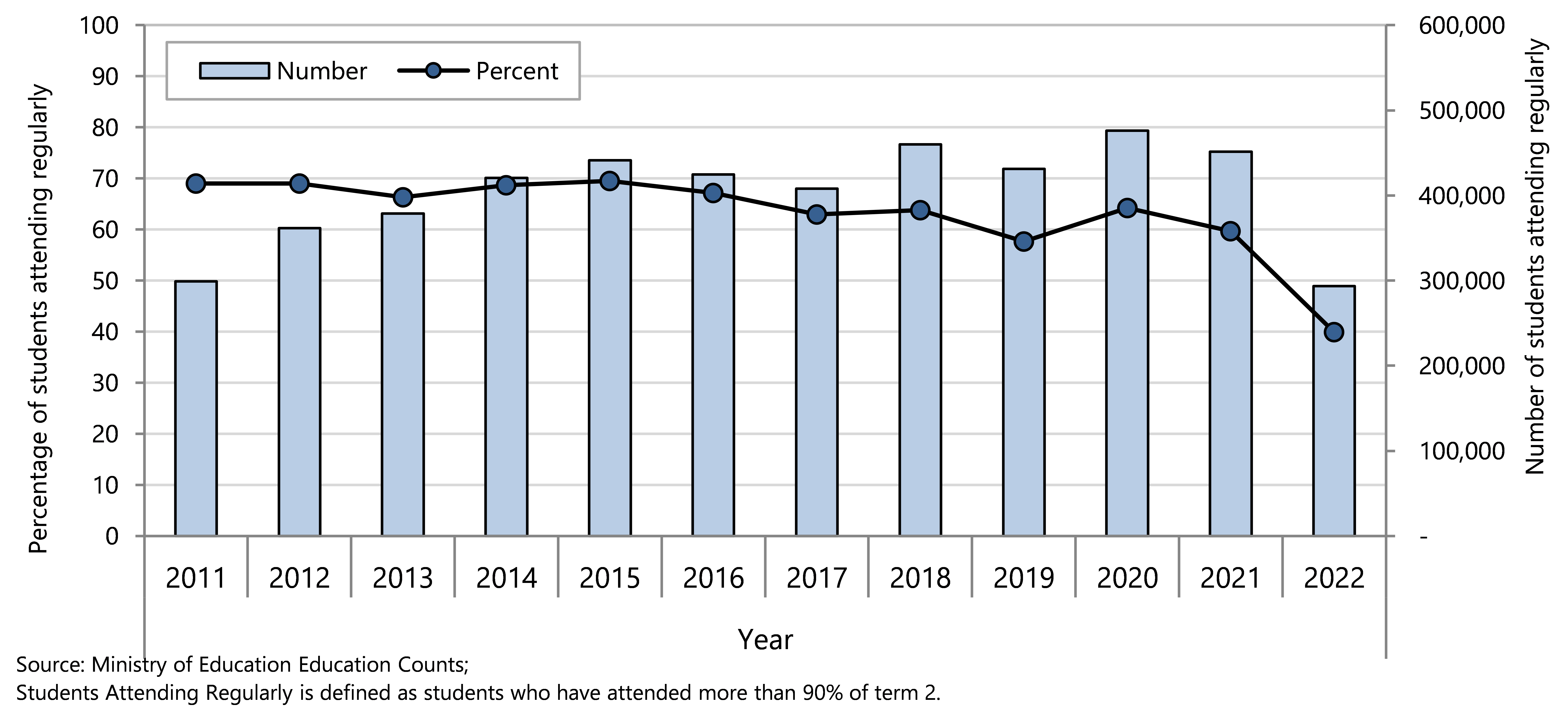

Additional information